This page is part of the Terminology Change Set Exchange (v1.0.0-ballot: STU1 Ballot 1) based on FHIR (HL7® FHIR® Standard) R4. No current official version has been published yet. For a full list of available versions, see the Directory of published versions

| Page standards status: Informative |

Over the past decades, biomedical terminologies have increasingly been recognized as key resources for knowledge management, data integration, and decision support [1]. Acceleration and development of Electronic Health Record (EHR) systems has precipitated the emergence of “standard terminologies” and their widespread adoption in the clinical community. These include Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT®), the Logical Observation Identifiers, Names, and Codes (LOINC®) and RxNorm. The availability of these clinical terminologies through the terminology services of FHIR is facilitating their usage in support of interoperability in healthcare.

Interoperability requires standardized semantics based on reference terminology provided by standards development organizations, professional organizations, or government agencies. These organizations publish their content with the intention of licensing it to health IT vendors, providers, and research organizations. In the U.S., the core clinical reference terminology is based on SNOMED CT®, LOINC®, and RxNorm. Healthcare organizations must adopt and integrate subsets or modules of various reference terminology and manage references, dependencies, versions, and releases. It is important for the integrity of medical records that the change history of concepts and value sets can be managed and tracked to allow the exchange of either current or retrospective medical records. Therefore, enterprise terminology requires integrated terminology using a common representation and management.

Despite the need to use standard terminologies in a highly integrated way, there is no standard representation across SNOMED CT®, LOINC®, RxNorm, etc. Some partnerships have been created among development teams to facilitate interoperability and minimize duplication of effort. Further integration has been proposed but will require additional resources to bring these terminologies closer together. However, while this evolution leads to greater compatibility and interoperability, integration of SNOMED CT®, LOINC®, and RxNorm is non-trivial as these terminologies use different formalisms and tools for their representation. Various terminologies have different semantics, models, release cycles, and versioning mechanisms [1]. While there is recognition that terminologies are not standardized at the exchange level, there is no consensus about harmonized next steps to solve the challenges.

This document focuses on the need for – and logical specification of – a Terminology Knowledge Architecture (Tinkar). The Tinkar Reference Model is a logical model that describes the standardized model for terminology and change management. Tinkar provides an architecture that delivers integrated terminology to the enterprise and its information systems. In doing so, it addresses the differences in management and structure across reference terminology, local concepts, and code lists/value sets.

Tinkar aims to adhere to the following statement from a publication about developments in clinical terminologies in the 2018 Yearbook of Medical Informatics [1]: “The benefits of the integrated terminologies in terms of homogenous semantics and inherent interoperability should, however, outweigh the complexity added to the system.” This specification provides the foundation of a knowledge architecture that is intended to integrate reference terminology from distributors (e.g., SNOMED CT®, LOINC®, RxNorm) with local concepts to support interoperable information semantics across the enterprise.

Information systems that are used across the healthcare enterprise record and manage clinical data using clinical statements and clinical terminologies in non-standardized ways. Interoperability specifications aim to require terminology bindings to concepts, code systems, and reusable value sets. Currently, there is variation in clinical data exchange across the enterprise, as existing payloads and clinical statements use inconsistent and highly variable enterprise terminologies. The management of the concepts, code systems, and value sets is non-trivial because developers, implementers, and end users are forced to manage “unnecessary complexity.” For example:

As a result of these complexities, there are many ways to say the same thing using standard terminologies and standard formats. The Institute of Medicine report, Health IT and Patient Safety: Building Safer Systems for Better Care, highlighted the unintended consequences of health IT-induced harm that can result in serious injury and death due to dosing errors, failure to detect serious illnesses, and delayed treatment due to poor human-computer interactions, confusing clinical terminology, or unreliable data quality [2]. Despite the widespread understanding of the importance of the quality of clinical data, there is currently a lack of integration and management of clinical terminologies across the healthcare enterprise.

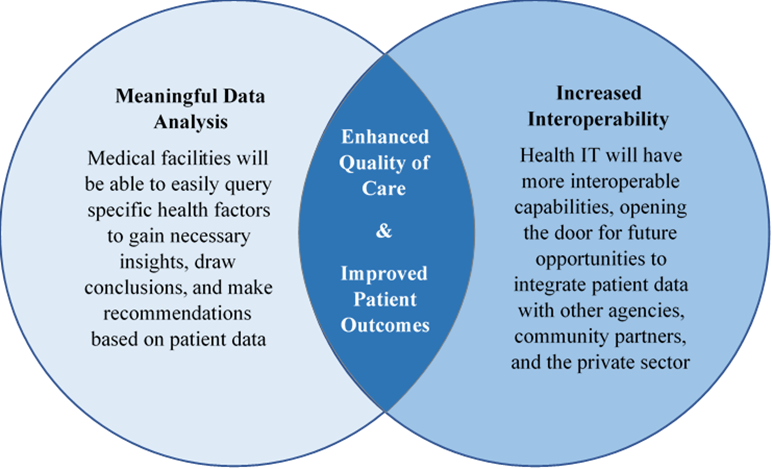

Tinkar intends to support integration of clinical terminology and local concepts to support increased data quality for interoperable clinical information. High-quality clinical data enables healthcare systems across the enterprise to conduct robust and meaningful data analysis and increase overall interoperability, which ultimately enhances quality of care across all medical facilities.

The following four high level potential deficiencies related to poorly integrated terminology and inefficient change management describe preventable harm that Tinkar addresses:

Consider the following examples of implementations that have gone wrong: [4][5][6][7]

Tinkar addresses challenges and problems from the above implementation examples:

| Challenge | Tinkar Solution |

|---|---|

| Uncoordinated or brittle terminology integration frequently breaks across systems | Standardize (and facilitate sharing) of terminology representation across systems |

[1] Bodenreider O, Cornet R, Vreeman DJ. Recent Developments in Clinical Terminologies - SNOMED CT, LOINC, and RxNorm. Yearbook Med Inform. 2018 Aug;27(1):129-139. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1667077. Epub 2018 Aug 29. PMID: 30157516; PMCID: PMC6115234.Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC6115234/.

[2] Institute of Medicine (2012). Health IT and Patient Safety. Building Safer Systems for Better Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

[3] Cimino JJ. Desiderata for controlled medical vocabularies in the twenty-first century. Methods of information in medicine. 1998;37(4-5):394-403.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3415631/.

[4] CBakken S, Campbell KE, Cimino JJ, Huff SM, Hammond WE. Toward vocabulary domain specifications for health level 7-coded data elements. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000 Jul-Aug;7(4):333-42. doi: 10.1136/ jamia.2000.0070333. PMID: 10887162; PMCID: PMC61438.

[5] Campbell KE, Oliver DE, Shortliffe EH. The Unified Medical Language System: toward a collaborative approach for solving terminologic problems. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998 Jan-Feb;5(1):12-6. doi: 10.1136/ jamia.1998.0050012. PMID: 9452982; PMCID: PMC61272.

[6] Campbell KE, Giannangelo K. Language barrier. Getting past the classifications and terminologies roadblock. J AHIMA. 2007 Feb;78(2):44-6, 48. PMID: 17366992.

[7] Campbell KE, Musen MA. Representation of clinical data using SNOMED III and conceptual graphs. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1992:354-8. PMID: 1482897; PMCID: PMC2248067.