This page is part of the SMART Health Cards and Links FHIR IG (v1.0.0-ballot: STU1 Ballot 1) based on FHIR (HL7® FHIR® Standard) R4. The current version which supersedes this version is 1.0.0. For a full list of available versions, see the Directory of published versions

This page contains additional guidance and information to implementers which is not part of the normative SMART Health Cards and Links specification.

See the SMART Health Cards public landing page.

No. SMART Health Cards are designed for use alongside existing forms of identification (e.g., a driver's license in person, or an online ID verification service). A SMART Health Card is a non-forgeable digital artifact analogous to a paper record on official letterhead. Concretely, the problem SMART Health Cards solve is one of provenance: a digitally signed SMART Health Card is a credential that guarantees that a specific issuer generated the record. The duty of verifying that the person presenting a Health Card is the subject of the data within the Health Card (or is authorized to act on behalf of this data subject) falls to the person or system receiving and validating a Health Card.

Decision-making often results in a narrowly-scoped "Pass" that embodies conclusions like "Person X qualifies for international flight between Country A and Country B, according to Rule Set C". While Health Cards are designed to be long-lived and general-purpose, Passes are highly contextual. We are not attempting to standardize "Passes" in this framework, but Health Cards can provide an important verifiable input for the generation of Passes.

The following tools are helpful to validate Health Card artifacts:

Other resources that are helpful for learning about and implementing SMART Health Cards include:

This RFC page in the SMART Health Cards GitHub contains RFCs related to SMART Health Cards.

The Libraries for SMART Health Cards wiki page includes suggestions about useful libraries.

Can someone steal my keys?

The issuer private keys must be generated, stored, and protected with great care, same as with PKI keys. The OWASP key management cheat sheet provides guidance on these items. To lower the risk of a key compromise, it is recommended to rotate issuance keys every year.

Can someone pretend to be me?

Health cards are digitally signed, using strong, state-of-the-art cryptographic algorithms. Health card forgery is only possible if someone

Can a rogue insider start issuing health cards?

Anyone with access to the issuer private keys can issue health cards under the issuer’s identity. Make sure these are generated, stored, and protected adequately. The OWASP key management cheat sheet provide guidance on these items. To reduce the risk of insider threats, an issuer should have good audit practices, and log when a health card is issued, and by which employee.

I found fraudulent health cards falsely issued under my name, what should I do?

Is the key used to issue these fraudulent health cards still in your published issuer public key set? If so, you need to retire that key immediately: delete the public key in the published key set and the corresponding private key. This will also invalidate all real cards issued under that key; contact your users to help them get a new health card.

If you don't recognize the key, are they tricking verifiers into thinking you are part of the same organization? Has the rogue key been listed as trusted in a trust framework? If so, follow the framework's method to have it removed.

I’m changing my keys, will my previously issued health cards still be valid?

Expired private keys should be deleted, the corresponding public keys should stay in the issuer published key set to allow verifiers to validate health cards issued using them. Revoked private keys (compromised, issued in error, etc.) should be deleted and removed from the published key set.

Some cards have been erroneously issued, can they be revoked?

Starting from v1.2.0, individual health cards issued by mistake can be revoked by listing its revocation identifier in an issuer's revocation list. Legacy health cards can use an external mechanism to derive a revocation identifier based on the health card's content. See the revocation section below for more details.

Can someone steal my health card?

A health card (digital file or paper QR code) is a “bearer” credential, anyone holding it can present it. Since all the contents of the health card is presented to verifiers, an attacker would need to have matching identifying information to use it illegitimately.

What if I lose my health card?

A health card file is a normal file, you can make back-ups. The QR code on a paper card contains all the digitally signed information to present to a verifier; presenting a backup photocopy or a picture of the QR code is enough for a verifier to validate the health card information.

Am I disclosing too much information when presenting a health card?

All the content of the health card is disclosed when presenting it. Issuers, wallet applications, and QR paper cards should clearly indicate what information is encoded and disclosed when presenting a health card.

How do I recognize forged health cards? Health cards are digitally signed, using strong, state-of-the-art cryptographic algorithms. It is infeasible to forge a health card without compromising a trusted issuer private key, and to modify one without invalidating its signature. Never rely solely on the textual elements of a paper card or a wallet app, always verify the cryptographic signature protecting the health card.

How can I trust the issuer of a health card?

The specified validation steps ensure that a presented health card was properly signed by an issuer key. How to trust that key is application/organization specific. In most cases, issuers will be part of a trust framework that verifiers will choose to accept (like how merchants accept Visa, Mastercard, AMEX). Verifiers therefore need to make sure the signing key is a valid identity in the frameworks they accept. For keys that are part of a directory-based trust framework, make sure the key is part of the trusted directory. For keys that are part of a PKI-based trust framework, make sure that:

A single, non-chunked Version 22 SMART Health Card QR contains two segments

shc:/) always has 20 header bits and 40 data bits for a total of 60 bits.1The max JWS size that can fit in a single Version 22 QR code depends on the remaining space, which depends on the error correction used.

76 bits are already reserved for the required segment headers and shc:/ prefix. The following table lists the total number of bits a Version 22 QR Code can contain.

| Error Correction Level | Total data bits for V22 QR |

|---|---|

| Low | 8048 |

| Medium | 6256 |

| Quartile | 4544 |

| High | 3536 |

Each JWS character is encoded into two numeric characters (As described in Encoding Chunks as QR codes) and each numeric character requires 20/6 bits.1

Thus we can determine the maximum JWS size for each error correction with the following:

JWS Size = ((Total Data Bits - 76 bits reserved) * 6/20 bits per numeric character * 1/2 JWS character per numeric character = (Total Data Bits - 76)*3/20

The results of the above rounded down to the nearest integer number of characters gives:

| Error Correction Level | Max JWS Length for V22 QR |

|---|---|

| Low | 1195 |

| Medium | 927 |

| Quartile | 670 |

| High | 519 |

References:

On March 19th, 2021, the WHO released Interim guidance for developing a Smart Vaccination Certificate. Here are some key distinctions to keep in mind with respect to WHO RC1:

Project names

WHO RC1 has a wider scope than SMART Health Cards; WHO's scope includes continuity of care in addition to proof of vaccination.

WHO RC1 assumes there will be national-level infrastructure for centralizing records for a given country. SMART Health Cards is designed to operate without this sort of central infrastructure.

WHO RC1 does not yet define technical details for active implementation, such as the specific format for QR codes and other artifacts.

WHO RC1 defines a data model for what should be included in a proof of vaccination. SMART Health Cards provides a similar data model via the SMART Health Cards: Vaccination & Testing Implementation Guide. The SMART IG aligns closely but not perfectly with WHO RC1 recommendations. Improving this alignment where possible is on the roadmap for the Vaccination & Testing Implementation Guide.

Starting from v1.2.0 of the SMART Health Card (SHC) framework, individual health cards issued by mistake can be revoked by listing its revocation identifier in an issuer's revocation list.

What should I use as a revocation identifier?

Issuers that keep track of every single issued SHC could create a per-SHC rid for fine-grained revocation. In many cases, an issuer will have an internal user ID that can be used to revoke all cards belonging to a particular user; using the timestamp feature allows an issue to invalidate cards up to a certain time.

Why is a one-way transformation on the user ID recommended for revocation ID?

Publishing an internal user ID might be a privacy issue. A one-way transform with high-entropy input prevents reversal of the CRL’s content. The proposed HMAC-SHA-256 algorithm using a 256-bit key achieves that.

Why are Card Revocation Lists tied to a key identifier?

Since SHC don’t have expiry dates, public keys and revocation information must be publicly available forever. Creating a per-kid CRL allows issuers to cap the size of CRLs, and verifier apps might not need to download the CRLs of old keys when the corresponding SHCs are replaced by newer ones.

Why is there a limit on the size of the revocation ID?

Per-design, SHC are small to fit into QR codes. Moreover, verifier applications might need to store the aggregated revocation information from many issuers; capping the rid size therefore limits the bandwidth and storage requirements of verifiers.

The recommended methods of taking the base64url encoding of the b4-bit truncated HMAC-SHA-256 output results in 11 characters. The 24-character limit allows the encoding of 128-bit values in base64url, if required by an issuer.

The consumer-facing SMART Health Cards site contains information oriented to patients.

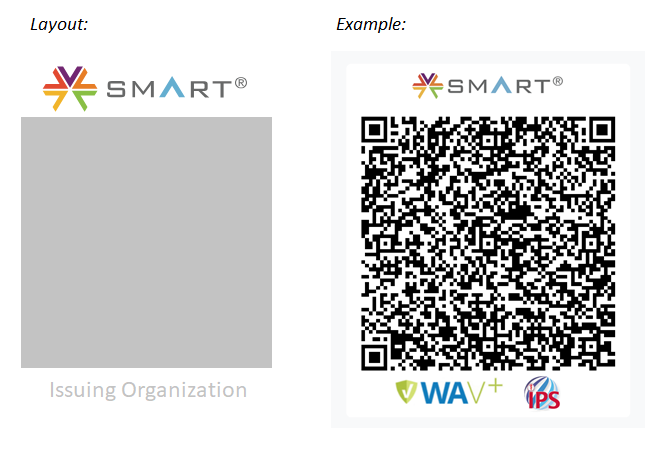

The community is currently discussing potential conventions for presenting QR codes associated with SMART Health Cards and Links in a consistent way–for example on a card issued by a healthcare agency or insurer–with the goal of helping patients easily recognize and use them.

Two general guidelines can help users recognize a QR as a SMART Health Card or Link and increase the reliability of their experience using it.

First, present the QR code in a three-layer stack arrangement that includes:

Second, avoid placing an icon within the QR code. Because SMART Health Cards and Links often hold a large amount of data compared to other QR codes, maximizing the area available for information and fault tolerance is important. And using a smaller icon to reduce the loss of data capacity will likely reduce its legibility.