This page is part of the Clinical Guidelines (v2.0.0: STU2) based on FHIR (HL7® FHIR® Standard) R4. This is the current published version. For a full list of available versions, see the Directory of published versions

Knowledge Engineering (KE) is the discipline and profession of developing explicit representations of advanced, domain-oriented logic in computer systems (i.e., knowledge-based systems) in order to simulate human decision-making and high-level cognitive tasks. A knowledge engineer supplies or develops some or all of the "knowledge," typically stored in some knowledge base(s), that is built into or used by computational systems.

This section will provide the following:

In healthcare, knowledge engineers are further specialized with expertise that may span from those with deep domain understanding including knowledge elicitation tools and techniques with some familiarity with various knowledge representation formalisms to deep understanding of knowledge formalism (i.e., representation/ expression) and knowledge architecture (i.e., knowledge processes and technology requirements for creating, capturing, organizing, accessing and using knowledge assets with varying degrees of familiarity with the domain.)

Furthermore, some knowledge engineers are very specialized in a particular knowledge representation level (see below) and or functional tier such as data modelers, terminologists, ontologists, and expression language (e.g., CQL) authors. Likewise, some knowledge engineers are very specialized in a healthcare domain (e.g., cardiology), broad domain conceptualizations and their respective formalisms (e.g., pathways, measures), or specialized methodologies that play a critical role in the overall knowledge engineering process (e.g., knowledge synthesis).

There are a few, experienced informaticians and knowledge architects that play a broader systems engineering (i.e., designing, integrating, and managing complex systems over their life cycles) role on a knowledge engineering team to bring the information, assets, processes, and individual knowledge engineers together, in part, through shared knowledge architecture and use of standardized representations (e.g., composite assets, terminologies, standards) as well as tooling (e.g., editors, validation tooling).

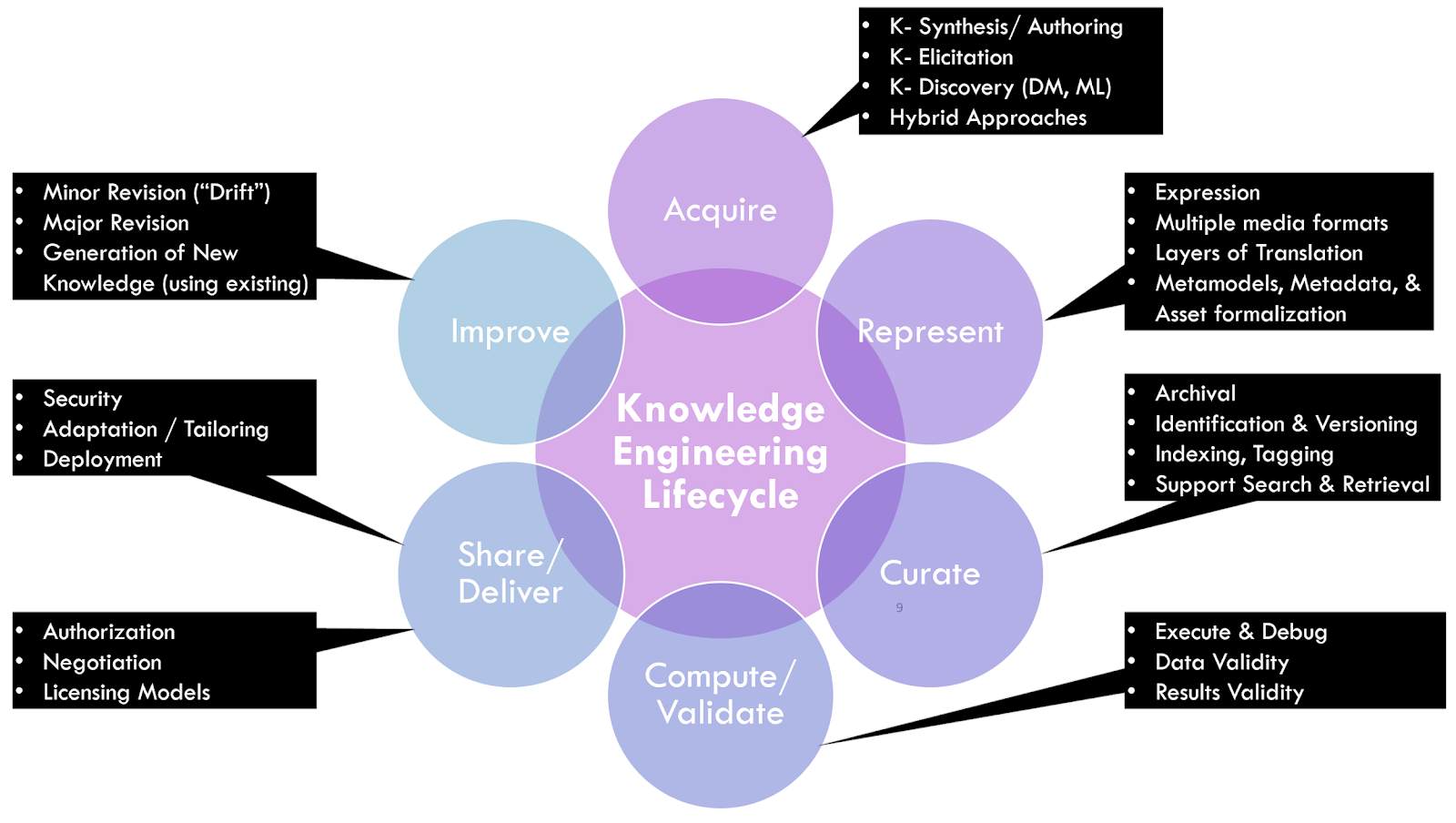

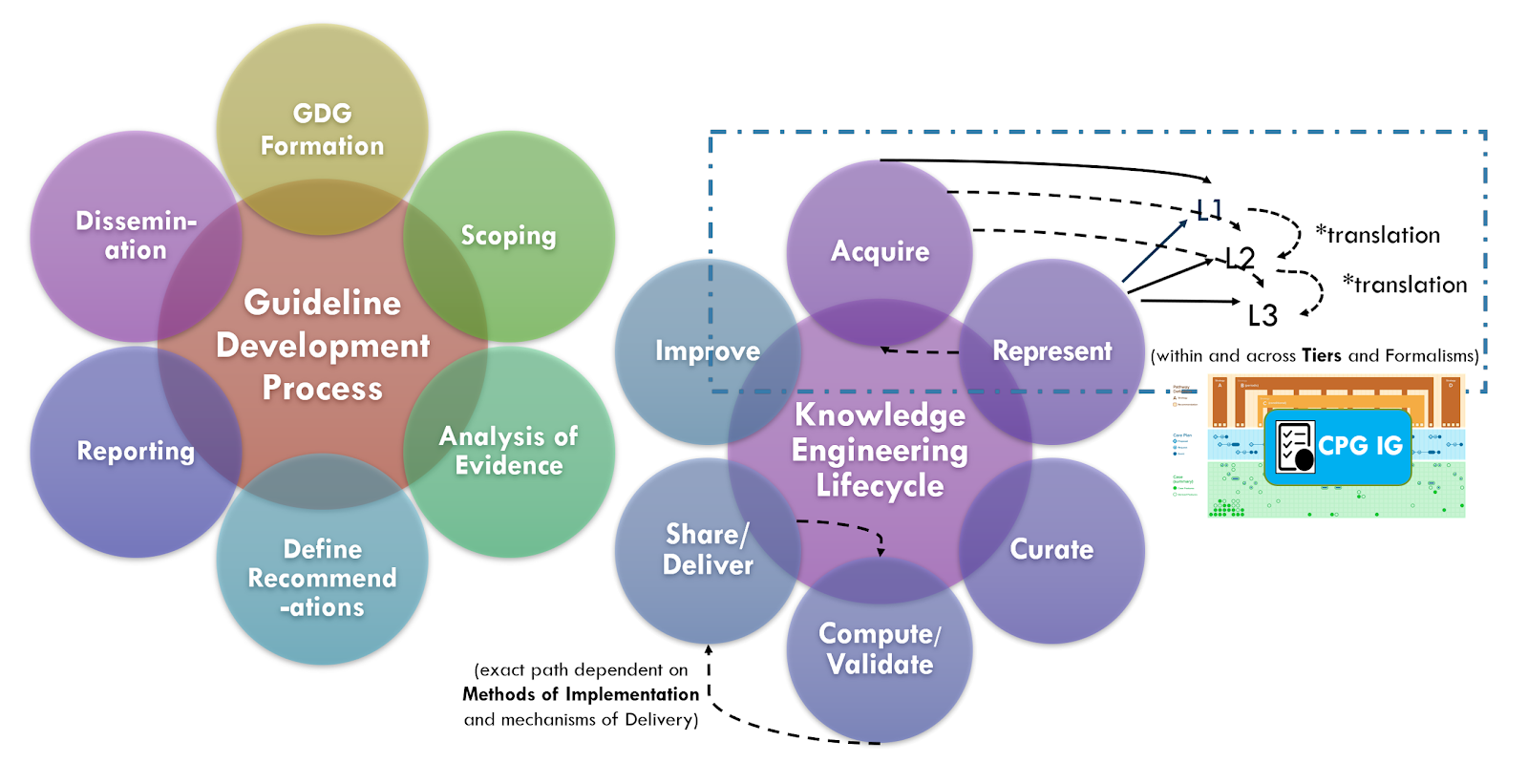

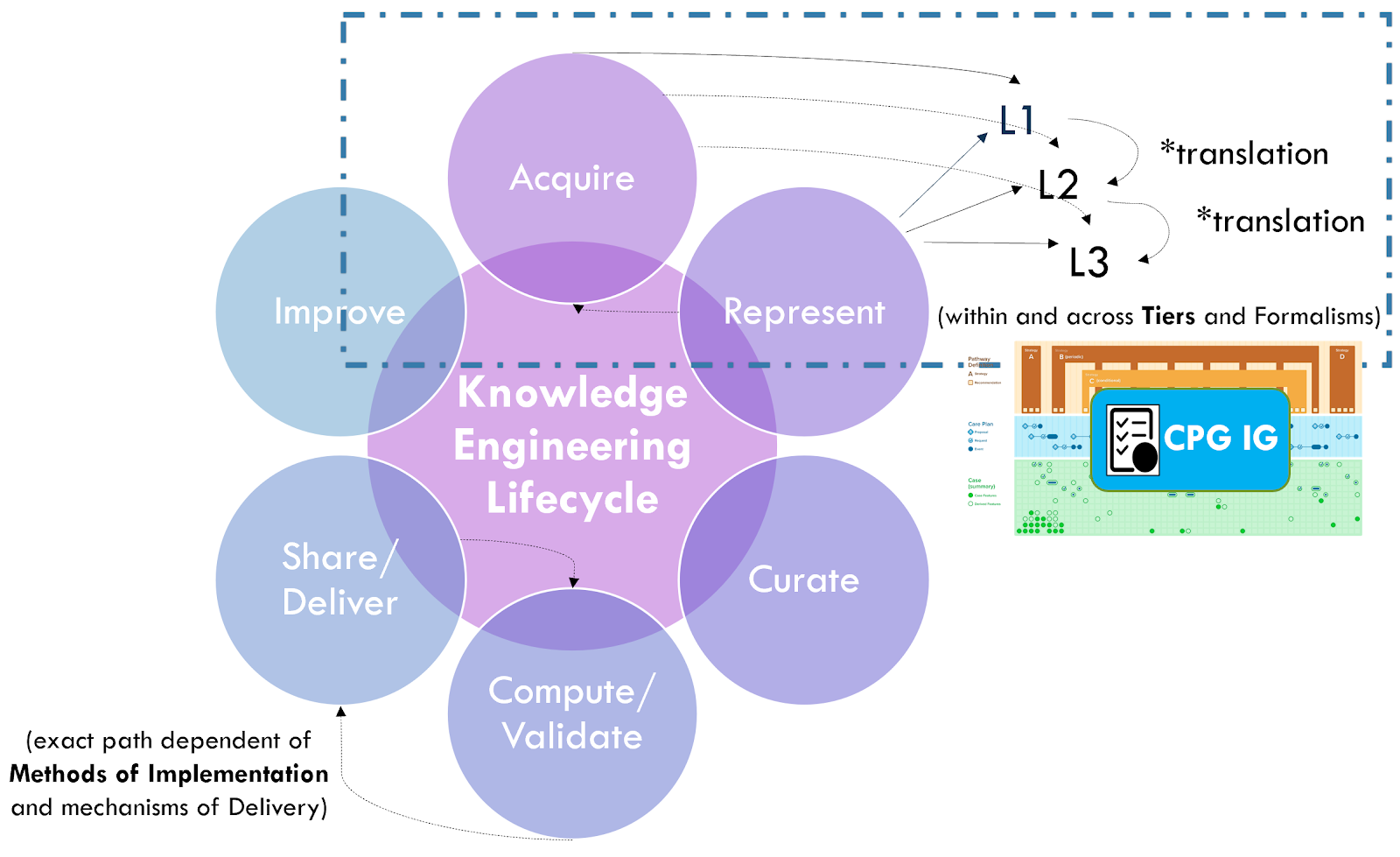

The knowledge engineering lifecycle process describes a progressively interdependent series of activities or steps taken in order to transform domain knowledge or content into a more formal computable set of assets for consumption, execution, and/or delivery. Furthermore, it describes many of the sub-activities and their work products as well as their interdependencies and generalized information flow. These activities, work products, and information have a generalized flow, however as discussed below in Agile KE, many of these activities and their derivatives run concurrently, have numerous touch points, and are done iteratively. These various flows occur between and across the various tiers of functionality (i.e., data, logic, user interface), levels of representation (i.e., narrative to computable), and knowledge formalisms (i.e., asset types, representations, and expressions) as presented in further detail below. Here we will briefly describe the high-level activities in the knowledge engineering lifecycle process, though much more detailed descriptions of these activities and their corresponding subactivies, methodologies, and tooling are available in various resources provided by respective communities of practice.

Knowledge acquisition is the process of extracting, understanding, structuring and organizing knowledge from one source, often solely or largely from human/ expert understandable formats, so it can be translated into computer-interpretable (or computer-enabled) formalisms. Knowledge acquisition typically includes one or more of the following sub-activities: knowledge elicitation, knowledge authoring, knowledge synthesis, knowledge discovery (data mining-machine learning DM-ML), and/or hybrid approaches that may include methods, tools, and information gained from a combination of the prior approaches.

Knowledge elicitation is the process of extracting an expert’s tacit knowledge (i.e., expertise and experience) or expert-sourced artifacts (e.g., narrative guidelines) to obtain a more formalizable representation of this knowledge.

Knowledge authoring is the process by which a domain expert directly expresses their tacit knowledge into more formalized representations of this knowledge.

Knowledge synthesis is a process and set of techniques that evaluates and summarizes all available evidence on a particular topic through comprehensive literature searches and advanced qualitative and quantitative synthesis methods.

Knowledge discovery is a process of discovering or learning patterns that lead to actionable knowledge from large data sets. This may be inclusive of various traditional data mining or data exploration approaches and tooling, numerous ML approaches, and/or combinations thereof. Using the CPG approach and the advantages of its Knowledge Architecture (e.g. separation of concerns, particularly for Case Features and eCaseReport), may afford new opportunities to leverage Knowledge Discovery across the full guideline lifecycle.

There is extraordinary value, critical efficiencies, and unique perspectives that can be gleaned from each of these knowledge acquisition approaches.

A key tenet of the CPG development process is for the knowledge engineering team to leverage early, often engagement and even integration with guideline development group. This allows the knowledge engineering team to start acquiring knowledge and translating it further upstream in the CPG development process. It further enables feedback and more rapid iteration between the knowledge engineering team and the domain experts in the guideline development group.

Knowledge acquisition approaches may further leverage the benefits of working directly with knowledge implementers, not limited to potential representative data sets (e.g de-identified data) to perform early knowledge specification and validation activities (e.g. data elements and terminologies) or even employ knowledge discovery and hybrid approaches as described above.

Knowledge translation occurs between and across various levels of knowledge representation, from narrative to semi-structured to structured to executable (described in detail below in “Knowledge Representation” section) as well as between equivalent forms of a given knowledge asset.

Knowledge representation pertains to the process of progressively structuring and formalizing content for computer interpretation and enablement and will be discussed in more detail in the "Knowledge Representation" section below.

Knowledge curation is the activity of identifying, versioning, indexing, tagging (i.e., adding metadata), and archiving the various artifacts and assets (e.g., representations, formalisms, expression libraries) relevant to the scoped knowledge engineering activity. The primary purpose for knowledge curation is to facilitate search and retrieval of relevant content.

Knowledge management has substantive ties to knowledge engineering, knowledge representation, knowledge creation, and knowledge sharing and further extends the broader concept of curation. Knowledge management refers to the processes, capabilities, and tooling for identifying, organizing, relating, finding, sharing, and reusing knowledge assets (see section on Knowledge Representation).

Knowledge execution refers to the processes of binding computable knowledge formalisms to data for the purpose of generating new information and insights. Details of knowledge execution are beyond the scope of this document, but has implications largely addressed in the section on “Methods of Implementation”.

Knowledge validation refers to verifying that the various knowledge formalisms faithfully, specifically, and unambiguously perform as intended. Validation may occur across tiers of functionality and levels of representation as well as for varying degrees of composition across levels and tiers (L x T). Validation may occur within and across various activities within the knowledge engineering lifecycle development process. Details of this section cover approaches for using Real-World Data to greatly accelerate the development and implementation processes and yield more accurate knowledge expressions.

Also see Test-driven Knowledge Engineering in Agile Approach to CPG Development

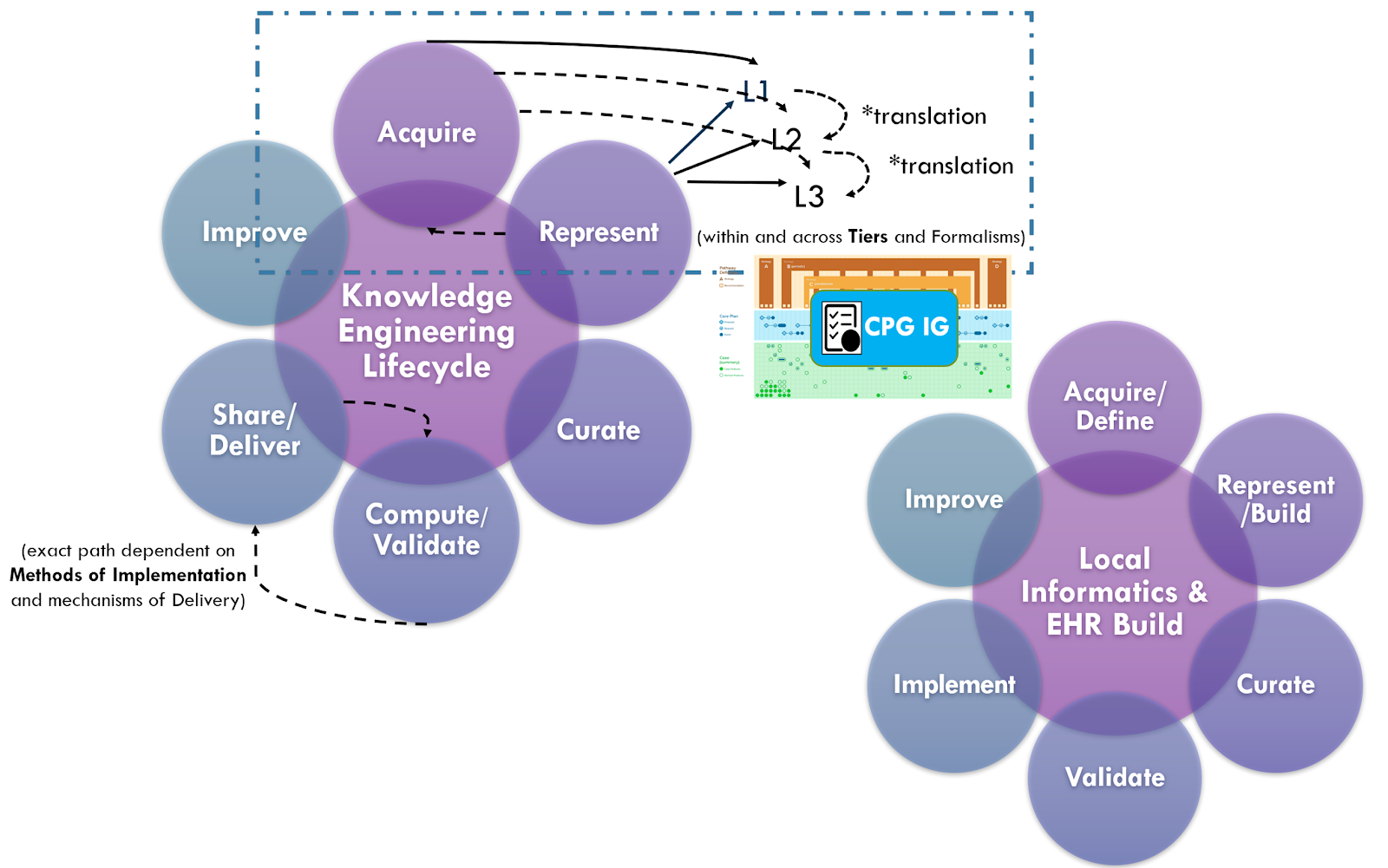

Knowledge implementation refers to the activities of localizing the knowledge formalisms, including addressing data bindings (e.g., data and terminology mappings), workflow insertions and localization factors (e.g., adjustments to thresholds), integration to end-user system endpoint interfaces, and adjustment or issues related to data quality, timing, enrichment, and/or required data enrichments. At minimum, there is a local data, clinical logic, and workflow validation step prior to full implementation.

While local implementations of guideline recommendations may warrant their own implementation guide, this implementation guide addresses several key factors and considerations related to local implementation. Native EHR build is out of scope.

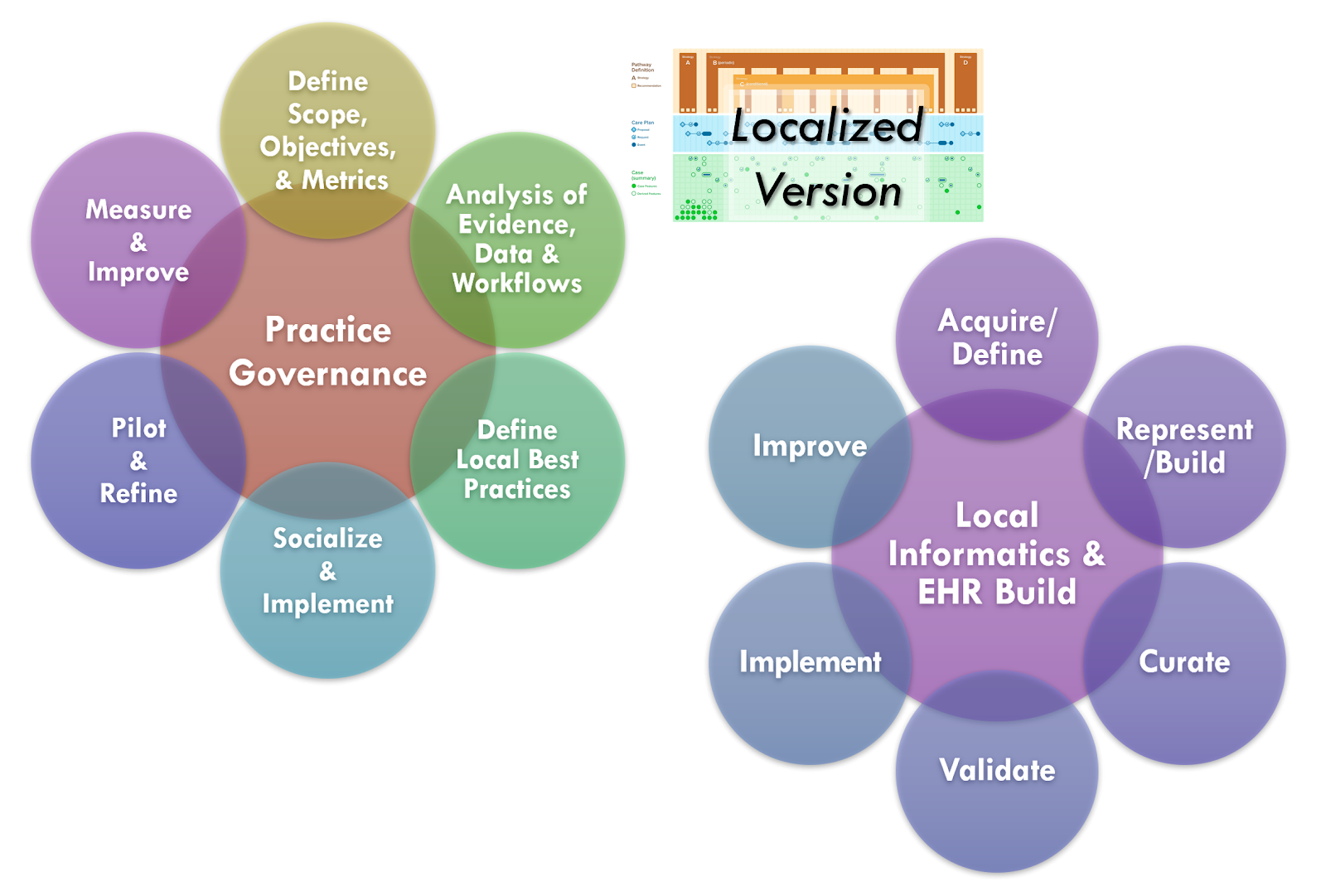

Most large health care delivery organizations have practice governance oversight bodies that may function in some degree like a guideline development group utilizing local organizational experts and key stakeholders, inputs from their own quality functions and research apparatus, and taking into account organizational goals, objectives, and limitations.

Just as many of the functions and methods of the guideline development group have their local analogues, so does the knowledge engineering and guideline formalization and implementation.

Given the similarities between and related activities of the CPG development process and the local implementation of standardized best practices, there are considerable opportunities for improving the effectiveness, efficiency, implementability, and overall uptake (and enhancement) guideline recommendations related best practices.

As described in more detail in the section on Knowledge Implementation, there are numerous analogues between the guideline development group and local practice governance as well as between the CPG knowledge engineering function and local informatics and EHR build functions. Likewise, as the guideline development group and knowledge engineering function collaborate in the CPG development process, so does the local practice governance and informatics/EHR build function in the local knowledge implementation process.

Furthermore, such a collaboration provides an opportunity to engage and address critical implementation concerns further upstream as well as afford earlier, shorter, and actionable feedback loops into the overall best practice to daily practice endeavor.

Such real-world data can not improve the quality (effectiveness and implementability) of the CPG, it affords the opportunity to greatly accelerate the knowledge engineering process and overall CPG development lifecycle. Obviously, having more than one local implementation affords many benefits.

Further details of knowledge implementation are beyond the scope of this document at this time, but have implications partially addressed in the section on “Methods of Implementation.”

The Agile CPG Development Approach describes methods, principles, and tools to develop and implement higher-quality CPGs more efficiently and timely.

This section will provide the following:

Also refer to the prior section on Knowledge Implementation for details on concurrent development and implementation using cross-functional integration with Local Implementation teams and the benefits thereof.

As implied by its name, Agile process and initiatives are able to move quickly and easily as has been demonstrated and accepted best practice in the software development industry. Agile development is characterized by the division of tasks into short phases of work and frequent reassessment and adaptation of plans.

Characteristics of Agile include:

Knowledge-driven systems principles and best practices must still be respected and/or employed.

Relevant Agile Practices to be adapted to knowledge engineering function:

Much more detail will be provided in the section dedicated to the Agile CPG Development Approach