This page is part of the Clinical Guidelines (v2.0.0: STU2) based on FHIR (HL7® FHIR® Standard) R4. This is the current published version. For a full list of available versions, see the Directory of published versions

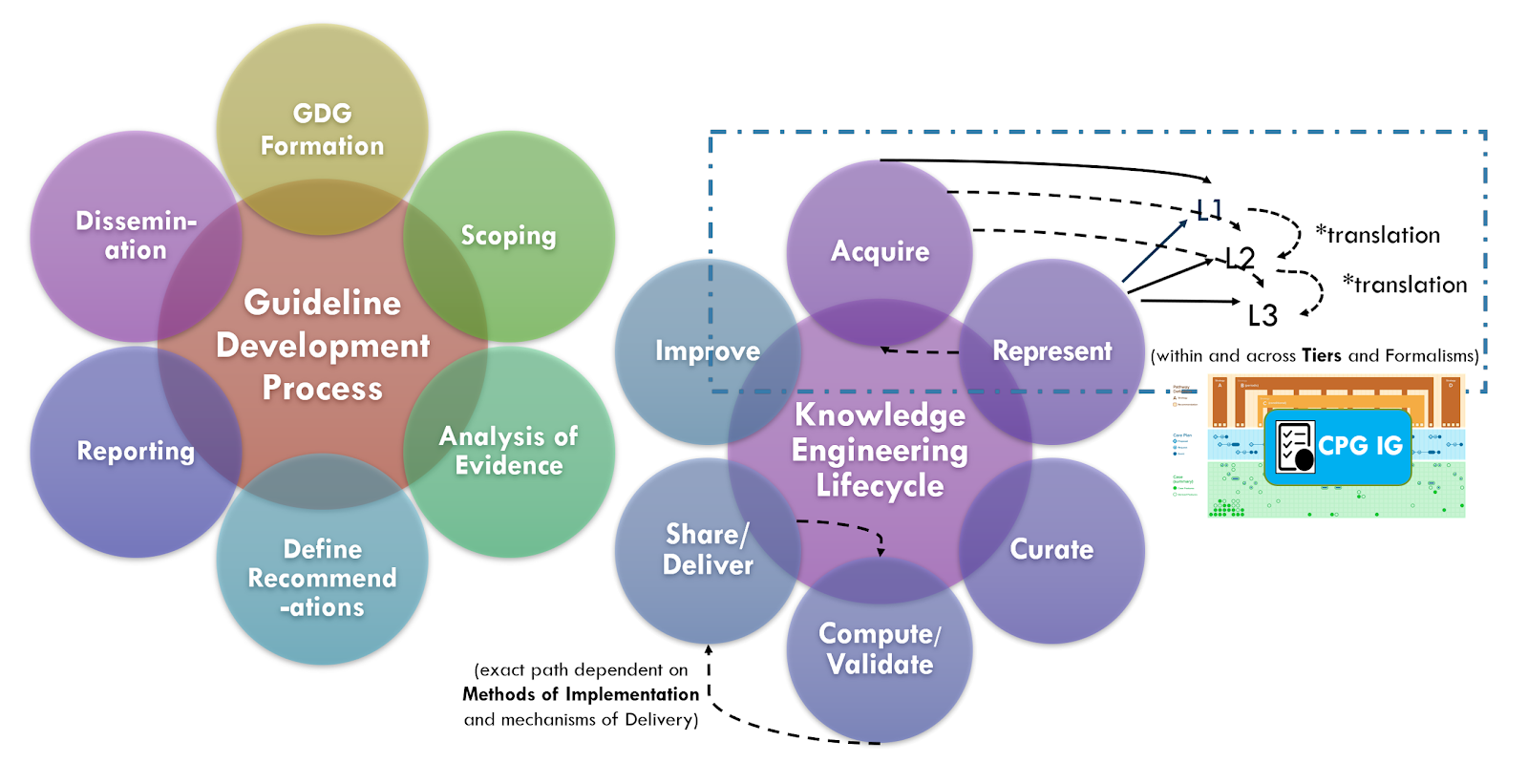

Knowledge translation has specific meaning within the knowledge engineering lifecycle process for knowledge engineers. However, there are at least three perspectives on knowledge translation that must be considered in the context of co-developing a clinical guideline together with its formal representation as a CPG. These include:

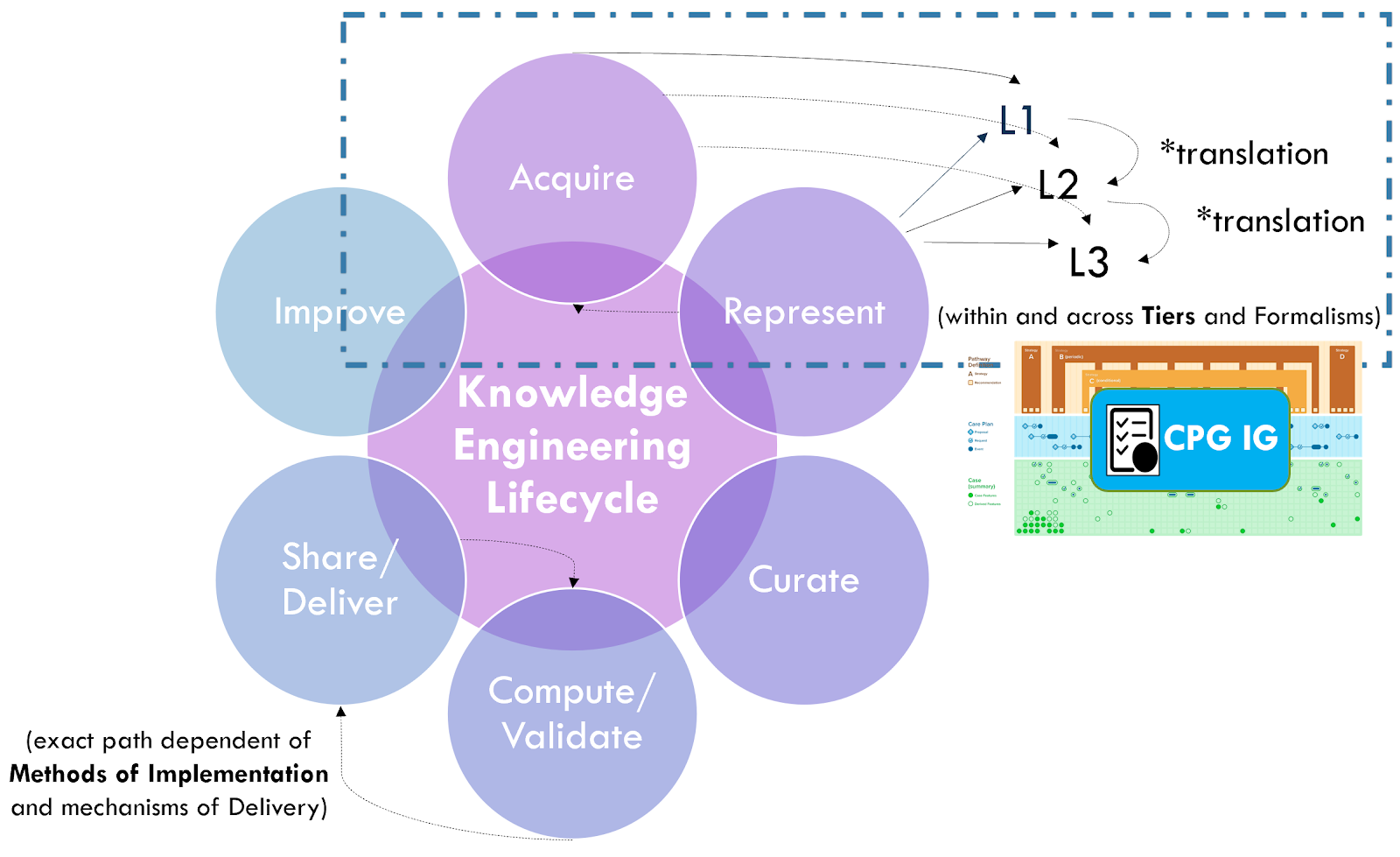

The broader perspective on clinical knowledge translation across the entire knowledge ecosystem provides perspective on various sources of knowledge and the nature of their content and metadata. In the classic approach to formalizing (components of) clinical practice guidelines, knowledge translation means the rendering of concepts, clinical logic, and intent of a narrative guideline into a computable formalism en masse after the narrative has been written, peer reviewed, and with the guideline development group often disbanded or moved on to another scope. In this case, the translation between and across levels of knowledge representation is a well-established activity for the knowledge engineer as is translation between levels and formalisms. Knowledge engineers often use tooling and techniques to address these activities, and some even take into consideration their respective touch points across the broader knowledge ecosystem.

See the section on Levels of Knowledge Representation for the approach and examples related to guidelines. The details of translating between and across these levels is beyond the scope of this implementation guide.

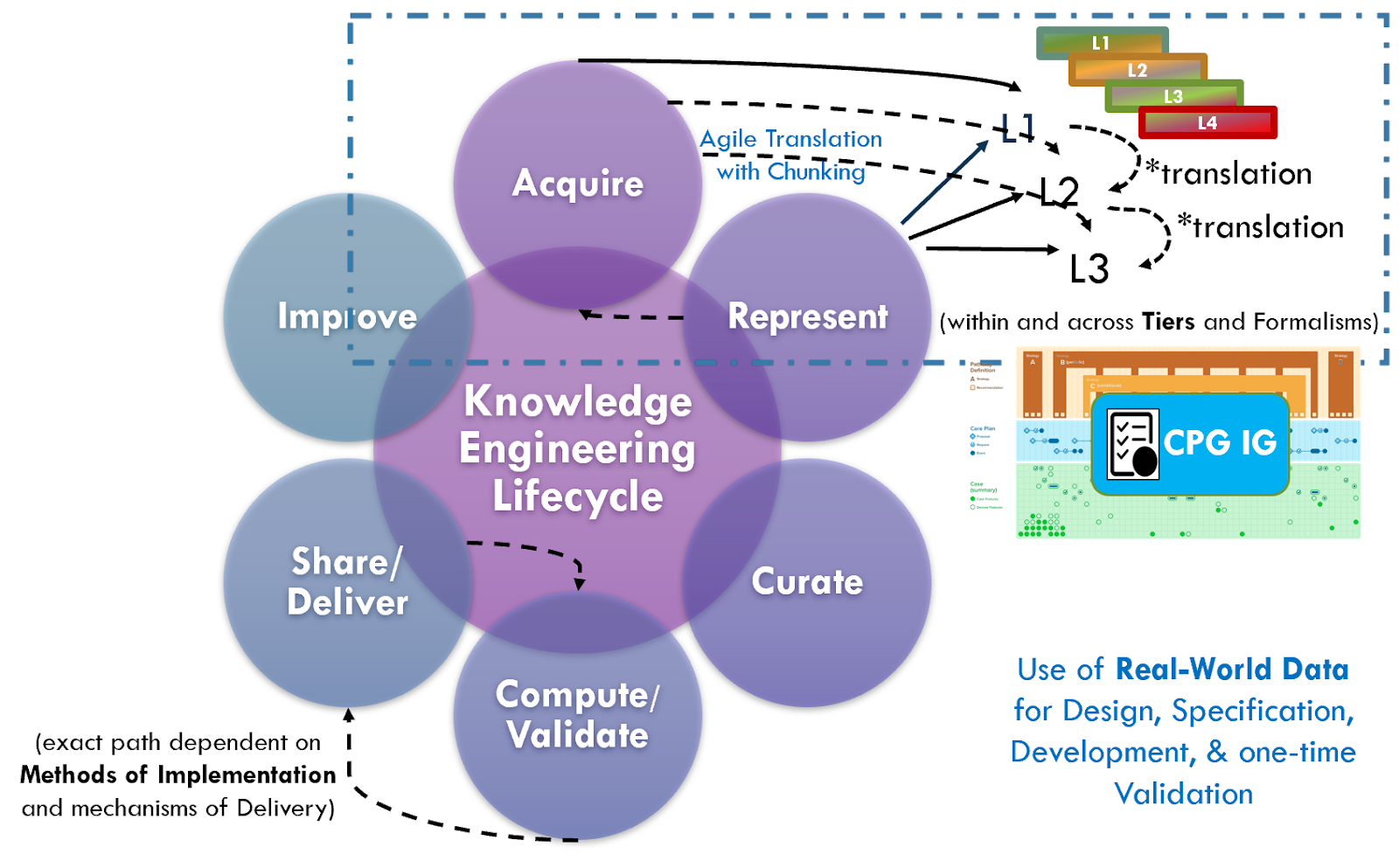

There are ongoing efforts, tool development activities, and knowledge resources across the knowledge ecosystem that may provide additional benefits in efficiency, timeliness, and effort that may be taken into consideration when developing a CPG. For instance, as described in the Guideline Development section on Analysis of Evidence, Recommendations, & Reporting Analysis of Evidence, the EBM-on-FHIR Evidence and Evidence Variables can carry descriptions and explicit value sets and standard terminologies for interventions and study population cohorts (and even reference CQL expressions for study population cohorts). Metadata on clinical research studies might afford the same. These may not be exact matches to the guideline scope (eligibility criteria) or recommendation interventions (FHIR activities and requests) and applicability criteria (Conditions in respective ECA Rules), but they may provide a reasonable start- and far earlier and upstream in an “Integrated Approach”. This early start on incremental pieces of the guideline is what is called “chunking” in Agile software processes described further in the section on The Agile CPG Development Approach.

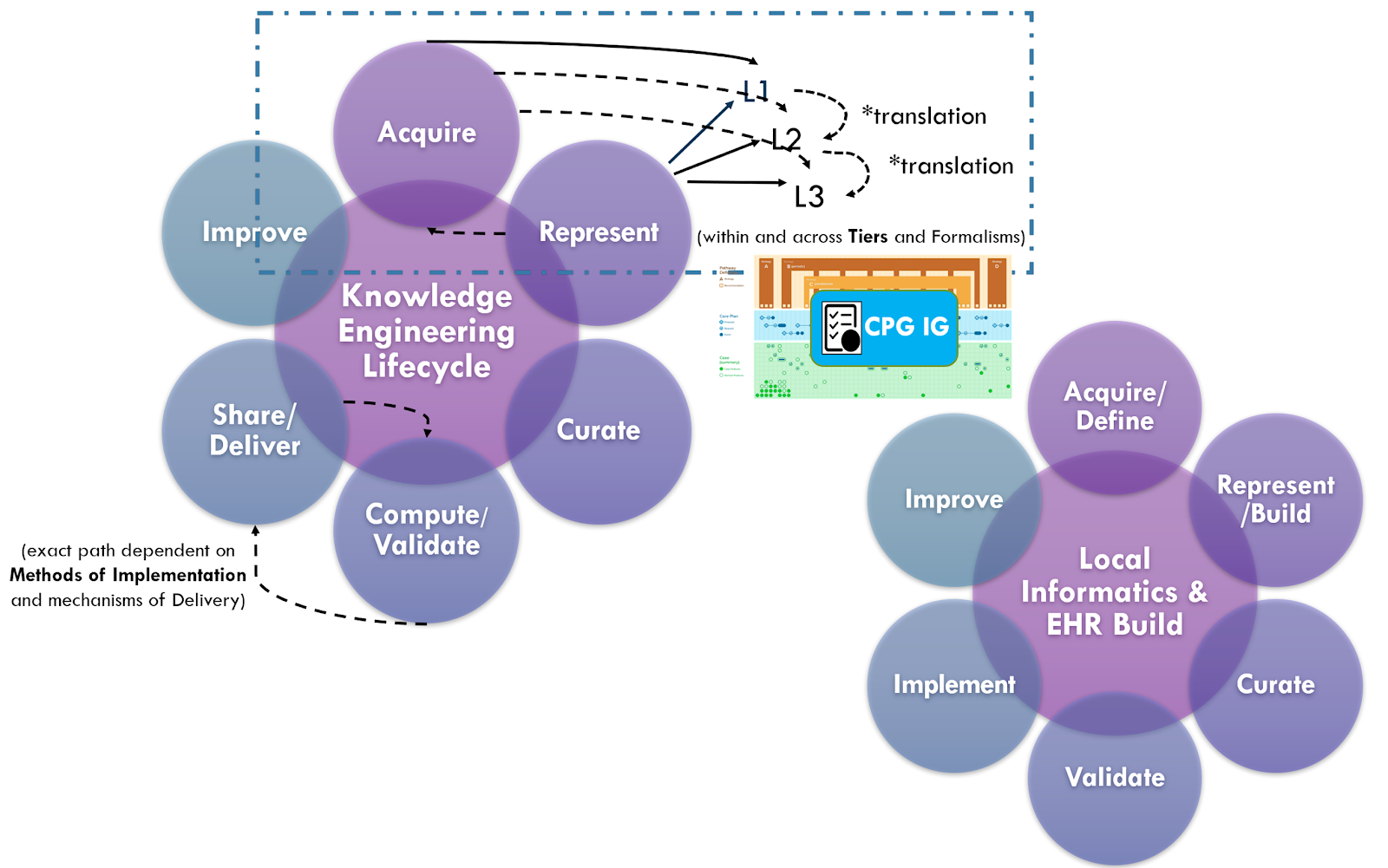

Furthermore, if started concurrently with or slightly lagging the guideline development group as suggested by the “Integrated Approach” from the CDC Adapting Clinical Guidelines for the Digital Age initiative, there are opportunities to begin the process of knowledge translation upfront in the guideline development process. Identifying terminologies and data definitions (e.g., FHIR resources) as well as modeling and testing cohort definitions and applicability criteria, perhaps against Real-World Data (particularly given a concurrent development and implementation effort) can begin early in the CPD development process and even provide feedback to the guideline development team.

The approaches above including “chunking” of incremental parts of the guideline, and use of real-world data for design, specification, development, and validation (including one-time validation vs multi-phased, sequential validation), combined with the “Integrated Approach” and concurrent guideline development and implementation (discussed in the section on Knowledge Implementation) are all part of the Agile CPG Development Approach.