This page is part of the Clinical Guidelines (v2.0.0: STU2) based on FHIR (HL7® FHIR® Standard) R4. This is the current published version. For a full list of available versions, see the Directory of published versions

Knowledge acquisition is the process of extracting, understanding, structuring and organizing knowledge from one source, often solely or largely from human/ expert understandable formats, so it can be translated into computer-interpretable (or computer-enabled) formalisms. Knowledge acquisition typically includes one or more of the following sub-activities: knowledge elicitation, knowledge authoring, knowledge synthesis, knowledge discovery (data mining-machine learning DM-ML and other forms of AI), and/or hybrid approaches that may include methods, tools, and information gained from a combination of the prior approaches.

Knowledge elicitation is the process of extracting an expert’s tacit knowledge (i.e., expertise and experience) or expert-sourced artifacts (e.g., narrative guidelines) to obtain a more formalizable representation of this knowledge. Techniques may include: expert interviews, ethnographic methodologies (e.g., artifact analysis, shadowing, retrospective cued recall interviews, critical decision method, contextual inquiry, case presentations or reviews, Delphi method [a forecasting process framework based on the results of multiple rounds of questionnaires sent to a panel of experts], concept mapping [a visual diagram that depicts concepts, their attributes, and suggested relationships between them from a domain perspective]). Numerous approaches are emerging to extract information from guideline narratives including tools for human extraction, the use of natural language processing

Knowledge authoring is the process by which a domain expert directly expresses their tacit knowledge into more formalized representations of this knowledge. This is often done using tools such as editors that facilitate the knowledge translation process through business logic affordances and constraints) in the tooling that provide mappings from domain concepts (e.g., expert mental models) to knowledge representations derived from knowledge asset meta-models defined by knowledge architects as well as pre-existing content from an established knowledge bases (e.g., ontologies and terminologies). The use of description logic and editors (e.g. Protege) to create a domain ontology for a CPG is one such example. Another may be the modification of the CDS Connect Authoring tool for ECA Rules that fit the CPG profiles (e.g. CPGRecommendations, CPGStrategies, and CPGPathways). Authoring tools enable a subject matter knowledge engineer to perform much of the knowledge translation activities, though some understanding of the target expression language is nearly requisite.

Knowledge synthesis is a process and set of techniques that evaluates and summarizes all available evidence on a particular topic through comprehensive literature searches and advanced qualitative and quantitative synthesis methods. This is analogous, if not identical to the knowledge synthesis and evidence-based practice community's Evidence Analysis Analysis of Evidence approach utilized by the guideline development group as described above. This is an opportunity for many touch points between the guideline development group in the knowledge engineering team in the “Integrated Process”.

Knowledge discovery is a process of discovering or learning patterns that lead to actionable knowledge from large data sets. This may be inclusive of various traditional data mining or data exploration approaches and tooling, numerous ML approaches, other AI approaches, and/or combinations thereof. It may also be inclusive of various health outcomes research and data science activities and may built upon large curated data sets (e.g., clinical, clinical research, and quality improvement registries; -omics data sets) as well as real-world evidence and metadata or insights from across the evidence ecosystem (e.g., knowledge synthesis outputs, clinical trial metadata). These methods of knowledge acquisition provide affordances and much promise for inputs from various CPG activities (e.g., content formalization and data enrichment expression such as inferred CPG_CaseFeatures) and feedback loops (e.g., eCaseReports). Of note to the knowledge engineer, it is critical to fit the knowledge discovery method to the use case and often requires collaboration between the knowledge engineer and a methodological expert.

Using the CPG approach and the, and its knowledge architecture components, such as Case Features and eCaseReport, may afford new opportunities to leverage Knowledge Discovery across the full guideline lifecycle. This may include improved logic for determining Case Features, probabilistic models for Case Features to be used in decision logic, and even discovering new Case Features (e.g. risk and severity scores, more and more precise descriptions of disease and/or clinicopathological states, new or improved data inputs for Case Features). The use of NLP in clinical settings is another emerging approach for Case Feature extraction where critical patient-level information is only, or nearly only available in clinical narratives. NLP mentions, concepts, or other features (or any other knowledge discovery method for that matter), may be further included as data inputs for expression logic for Case Features. This is currently being done for quality measures (ref), has an expression language related to CQL (ClarityNLP) for clinical phenotyping, and is on the near-term roadmap as a built-in feature for CQL.

These Case Features could serve a role in the guideline and CPG development process as well as potentially serve as a feedforward mechanism for implementations (e.g. as supporting information for decisions for Proposals as part of a CPGCasePlanSummaryView, or for “patients-like-me” near real-time queries to compare cohorts and their outcomes against recommended and alternative interventions). And such machine-assisted Knowledge Discovery approaches could certainly play a role in the 6S Evidence Pyramid and Learning Health Systems. 6S Evidence Pyramid and Learning Health System(s)

Knowledge acquisition for Recommendations (including their respective decision logic and/or the use of newly discovered Case Feature or Case Feature attributes) acquired through Knowledge Discovery approaches will almost certainly need to go through some vetting by the evidence ecosystem and guideline development group to be used in expert body guideline recommendations. The discovery or hybrid approaches (discussed below) may greatly accelerate this process and rapid reviews and updates may fast-track such recommendations in critical situations such as new and poorly understood clinicopathophysiology (new or emergent diseases such as pandemics due to novel contagions) with poorly or unknown diagnostic, treatment, and preventative best practices. This is not yet well understood and beyond the scope of this implementation guide.

There is extraordinary value, critical efficiencies, and unique perspectives that can be gleaned from each of these knowledge acquisition approaches. In addition to knowledge gained from combining insights from each of these communities of practice, there are valuable knowledge and gains in efficiency in combining techniques and tooling as well as more discrete fragments of knowledge gained within sub-activities across these communities (called transdisciplinary and/or hybrid approaches). Using inferred Case Features (including process and outcome metrics from eCaseReports) as the data substrate for machine-assisted approaches is one such example. Using NLP features or concepts in expression logic for Case Features is another. In fact, many of the approaches described in the Knowledge Discovery section above are actually Hybrid approaches.

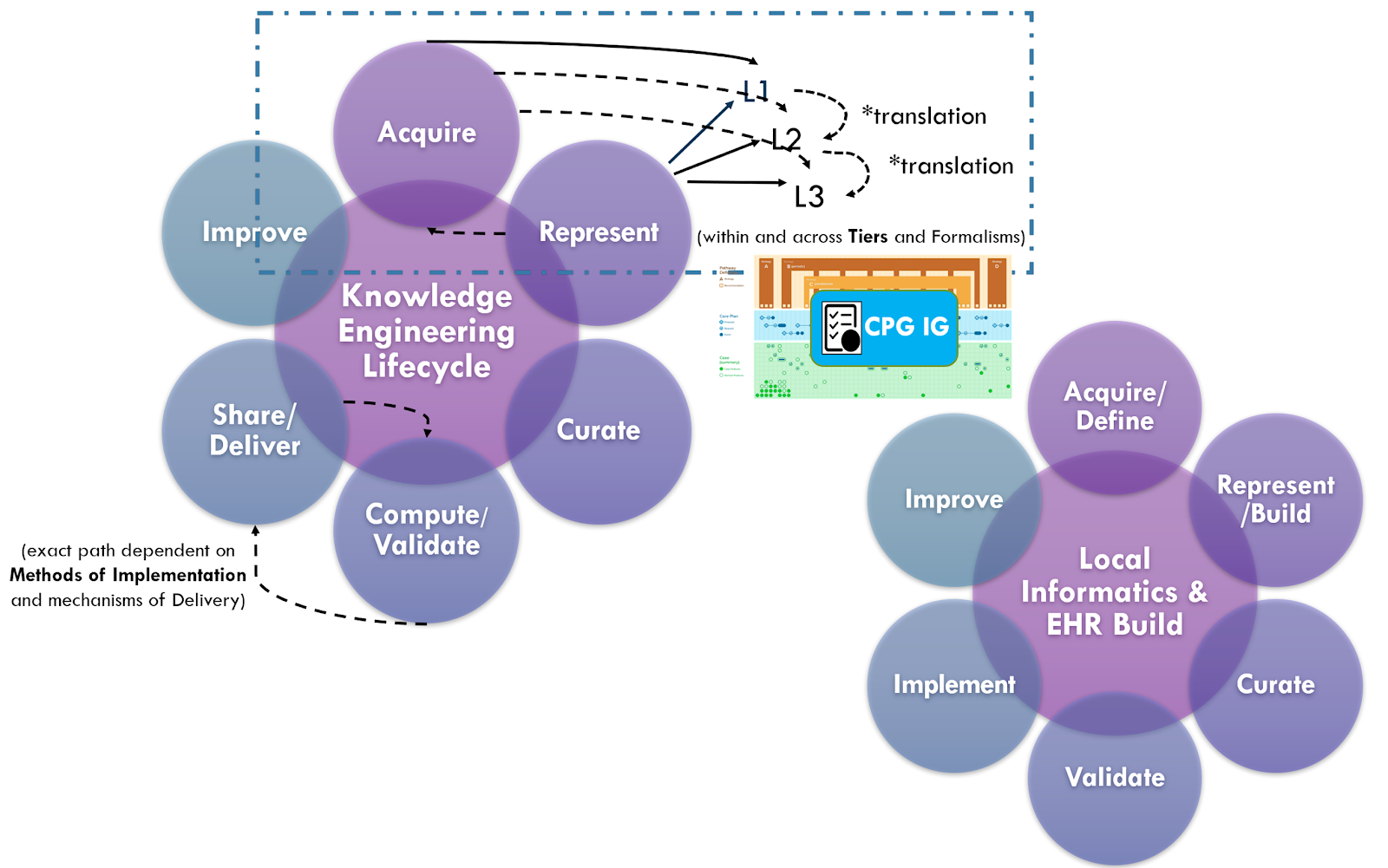

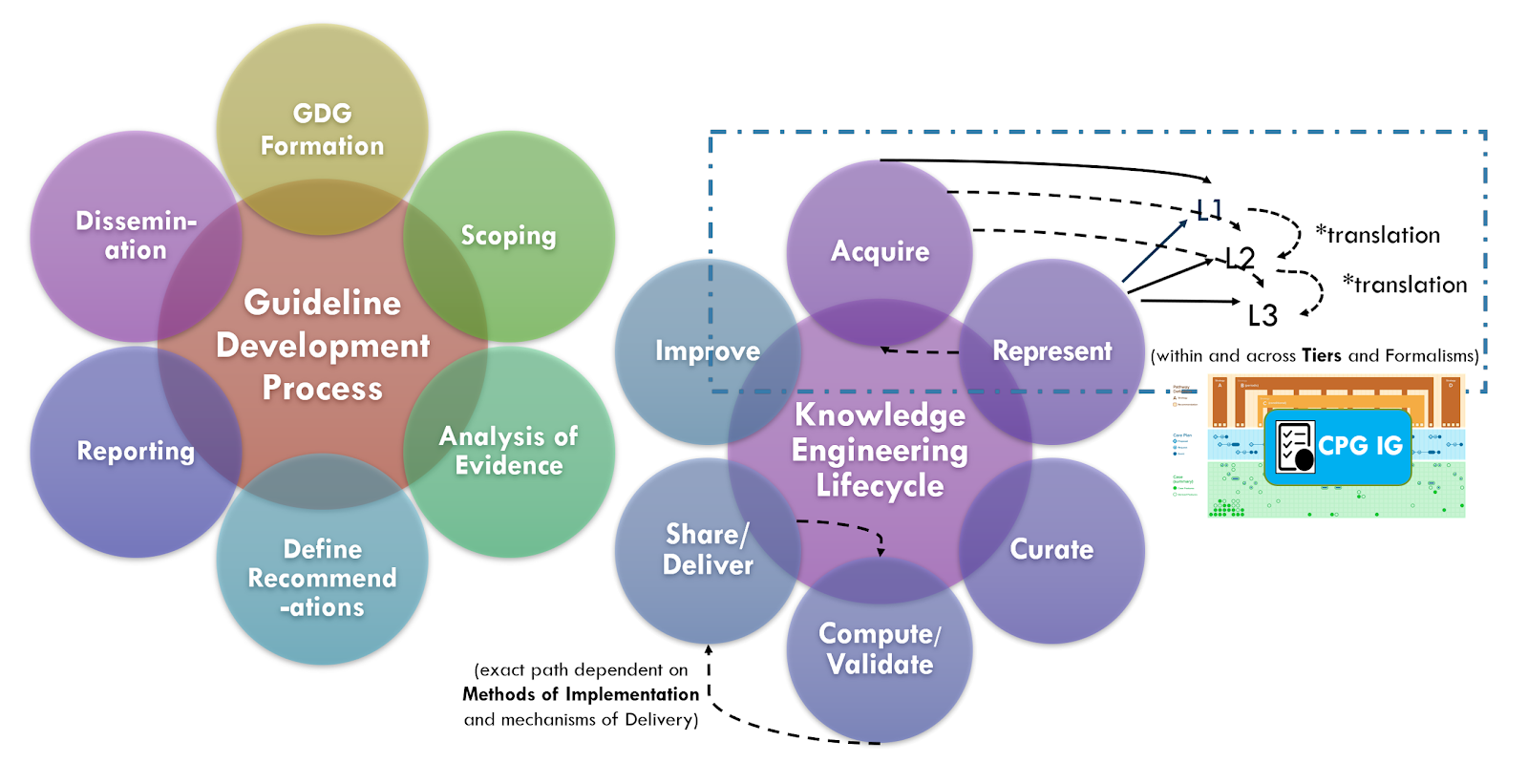

A key tenant of the CPG development process is for the knowledge engineering team to leverage early, often engagement and even integration with guideline development groups. This allows the knowledge engineering team to start acquiring knowledge and translating it further upstream in the CPG development process. It further enables feedback and more rapid iteration between the knowledge engineering team and the domain experts in the guideline development group.

A key tenant of the Agile CPG approach described subsequently, is to further integrate the knowledge engineering team and guideline development group into a nearly singular cross-functional team. Benefits include fewer handoffs and queues, concurrency of work efforts, shorter and more valuable feedback loops, and higher-quality inputs to knowledge acquisition (people and processes versus a paper narrative to be interpreted subsequently to and asynchronously with the guideline development group’s and artifacts). Lastly, but none of least importance is the ability for the guideline development group in the knowledge engineering team to learn together. Additional benefits and work processes are described subsequently.

Knowledge acquisition approaches may further leverage the benefits of working directly with knowledge implementers, not limited to potential representative data sets (e.g de-identified data) to perform early knowledge specification and validation activities (e.g. data elements and terminologies) or even employ knowledge discovery approaches as described above. Even CPGCaseFeature definitions (including inferred) or explicit recommendation semantics may be informed by various local implementation artifacts (e.g. CDS content, local clinical registry data elements and logic, workflow analysis artifacts). For further descriptions, see section on Concurrent Development and Implementation in Knowledge Implementation.

Collaboration with knowledge implementers further affords the potential for access to Real-World Data, including for knowledge acquisition. GIven a cohort of implementers with sufficient sample size and natural variation of Cases, the above Knowledge Discovery and Hybrid approaches to knowledge acquisition become not only more possible, but afford numerous benefits across the entire guideline lifecycle. Further information on approaches and benefits to Concurrent CPG Development and Implementation Knowledge Implementation, doing so in the context of the Agile CPG Development Approach, and its relationship to enabling the 6S Evidence Pyramid and Learning Health System(s) can be found in these respective sections.