This page is part of the Clinical Guidelines (v1.0.0: STU 1) based on FHIR (HL7® FHIR® Standard) R4. The current version which supersedes this version is 2.0.0. For a full list of available versions, see the Directory of published versions

Separation of concerns is a design principle that creates a distinct and focused attention on each aspect of the domain or topic. This means that, from each aspect’s point of view, the other aspect(s) are irrelevant; but it does not mean that the other aspects are ignored. It is “being one- and multiple-track minded simultaneously.” (ref ). This concept has been used to address efficient and effective approaches in software engineering, particularly as they pertain to developing larger, more complex information systems. (ref) The most common application of this principle is to a three-tiered architecture (i.e. data, logic, UI) and corresponds to the tiers of functionality discussed earlier.

In medicine, a very similar principal led Dr. Larry Weed to describe the problem-oriented approach to the medical record and reasoning about patients’ concerns, including the well-known and commonly used approach to the SOAP note (Subjective, Objective, Assessment, and Plan).1 Dr. Weed proposed that physicians were essentially scientists, except that as many scientist pursue a singular (or few) hypotheses throughout there careers, a physician must formulate and assess/test hypotheses for a given patient and often throughout the day and therefore must break each issue down into a concern or problem. Problem-orientedness and the SOAP note have further been shown to be an effective cognitive framework for assessing and addressing patient concerns.2 Interestingly, Dr. Weed’s problem-oriented approach and SOAP note do play into the CPG knowledge architecture, though not exclusively. In healthcare activities, there are at least several related but orthogonal axes on which to separate concerns.

One major axis of separation is by each disease or condition, intervention (e.g., procedure, therapy), and/or diagnostic (e.g., imaging, tests), though these concerns often intersect or interact significantly. Similarly, care setting (e.g., ambulatory, home, inpatient, ED, ICU) and generalized type of care activity (e.g., surveillance, prevention, diagnostic workup, treatment planning, disease and therapeutic response surveillance, recovery/convalescence, survivorship) can be conceptualized further as separations of concerns. Many of these separations are addressed through the scoping exercise of the guideline development group and a given guideline intentionally focuses on a singular topic or area of concern. This separation of concerns may be addressed by entirely distinct CPG’s or by Strategies within individual CPG’s. Relationships or interactions between separate CPG’s (or Strategies) may be addressed at the level of each separation (e.g., Plan-to-Plan, Case-to-Case) across CPG’s or by explicitly referencing features within a given separation of one CPG and following the same patterns of interactions between separations. The latter should be done explicitly (e.g., by referencing and including the requisite Case Features within all CPG’s whose Plan’s need to reason over them).

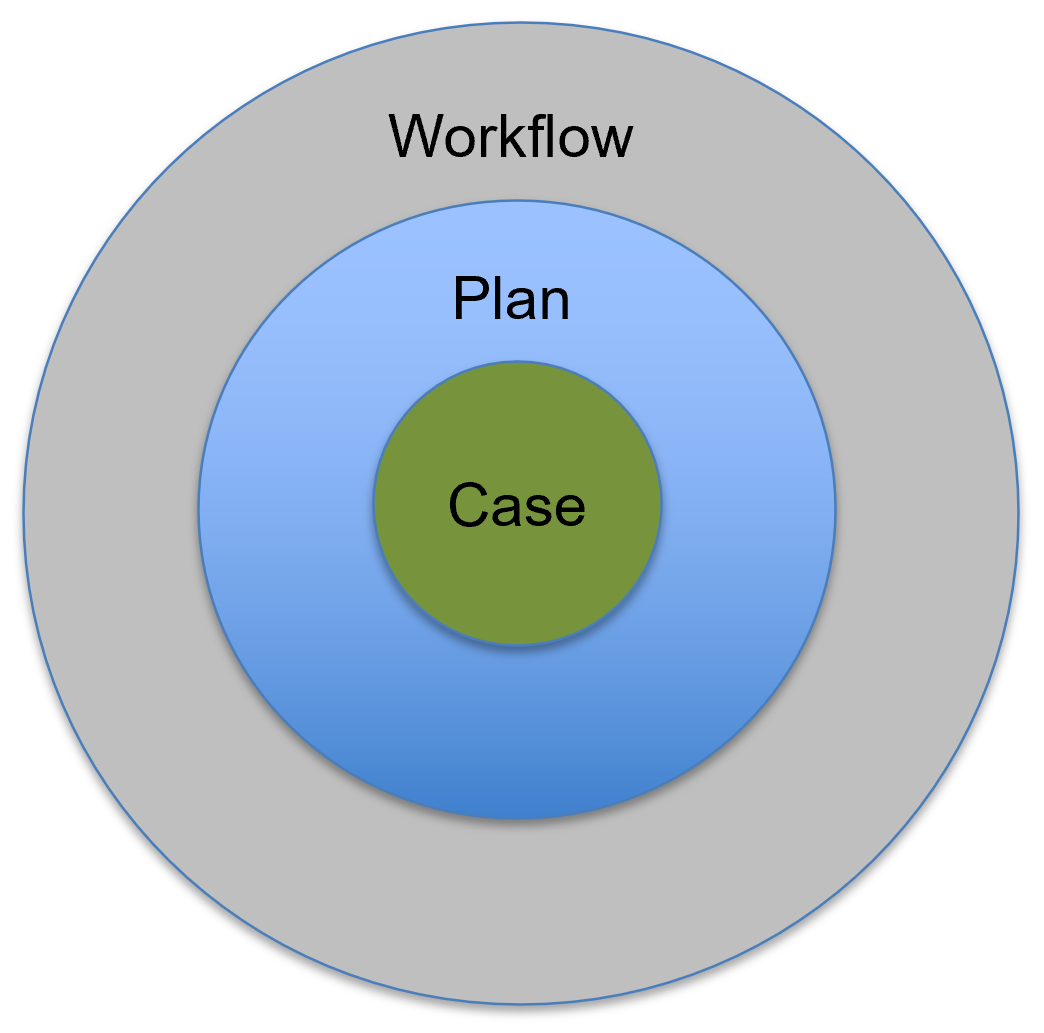

Another major axis of separation is by kind of process, including: 1) patient clinicopathological (i.e., pathophysiological and correlated clinical manifestations) processes, inclusive of normal physiology (CPGCase); 2) clinical decision-making and corresponding care processes as abstract from specific care settings (CPGPlan); and 3) care delivery process or clinical workflow by which the care processes are carried out in the context of a specific care setting where multiple patients and healthcare professionals undergo, situational activities, which may be inclusive of clinical information system or EHRs. The CPG-IG knowledge architecture is designed to respect the separation of these concerns as discussed below.

A third major axis of separation of importance to the CPG implementation guide is significantly related to the clinical workflow separation mentioned above, which itself may be separated into the real-world care delivery activities, those activities that are carried out in the context of clinical information systems (e.g., EHRs), and the means of interacting and relating to the Case and Plan. This separation is covered in further detail in the section on Workflow and Common Pathway in this implementation guide.

1: Jaroudi, Sarah; Payne, J. Drew DO Remembering Lawrence Weed: A Pioneer of the SOAP Note, Academic Medicine: January 2019 - Volume 94 - Issue 1 - p 11 doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002483

2: Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014 Nov; 21(6): 964–968. Published online 2014 May 28. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002776