This page is part of the Clinical Guidelines (v1.0.0: STU 1) based on FHIR (HL7® FHIR® Standard) R4. The current version which supersedes this version is 2.0.0. For a full list of available versions, see the Directory of published versions

The FHIR Clinical Guidelines Implementation Guide (CPG IG) provides a means of creating a computable representation of a narrative clinical guideline that is faithful to guideline intent and supports the derivation of downstream capabilities such as cognitive and decision support, quality measures, case reporting, and documentation templates that direct clinical documentation in support of determining guideline compliance.

Known Issues:

These issues are all related to various publication tooling issues. A technical correction is planned once the tooling issues have been addressed.

This implementation guide is organized into the following sections, accessible via the menu bar at the top of every page:

This implementation guide supports the development of standards-based computable representations of the content of clinical care guidelines. Its content pertains to technical aspects of digital guidelines implementation and is intended to be usable across multiple use cases across clinical domains as well as in the International Realm.

This implementation guide has been developed through a multi-stakeholder effort, holistically involving a range of stakeholders, including those who work at the beginning of the process (e.g., guideline developers) to the end users (e.g., clinical implementation team representatives, health IT developers, patients/patient advocates), and others in between (e.g., informaticists, communicators, evaluators, public health organizations, clinical quality measure and clinical decision support developers).

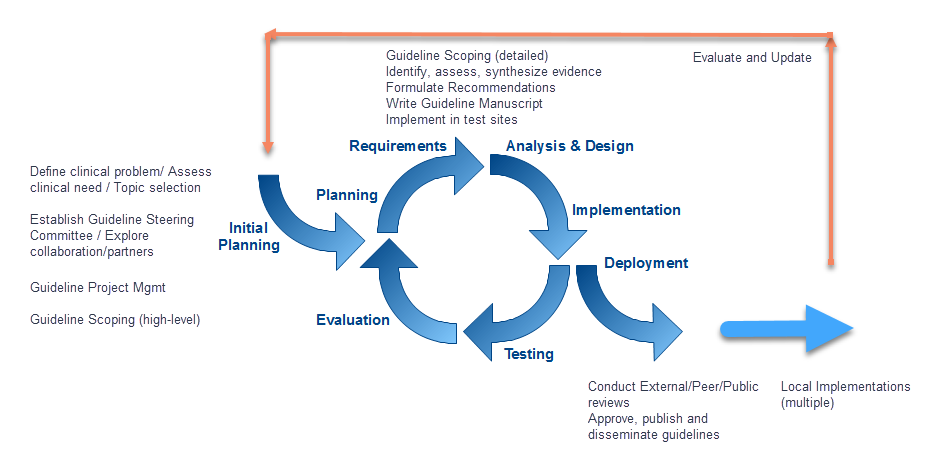

The premise involves determining the representation of clinical practice guideline recommendations in FHIR as part of an iterative guideline development and implementation process (Figure 1.1). By including all the relevant perspectives (e.g., guideline authors, informaticists, implementers, communicators, evaluators) as part of the iterative process, the resulting computable representation of the recommendations should be well-vetted and more readily implemented across multiple clinical domains.

Figure 1.1 Iterative Guideline Development and Implementation Process (Willet, D., University of Texas Southwestern, 2018)

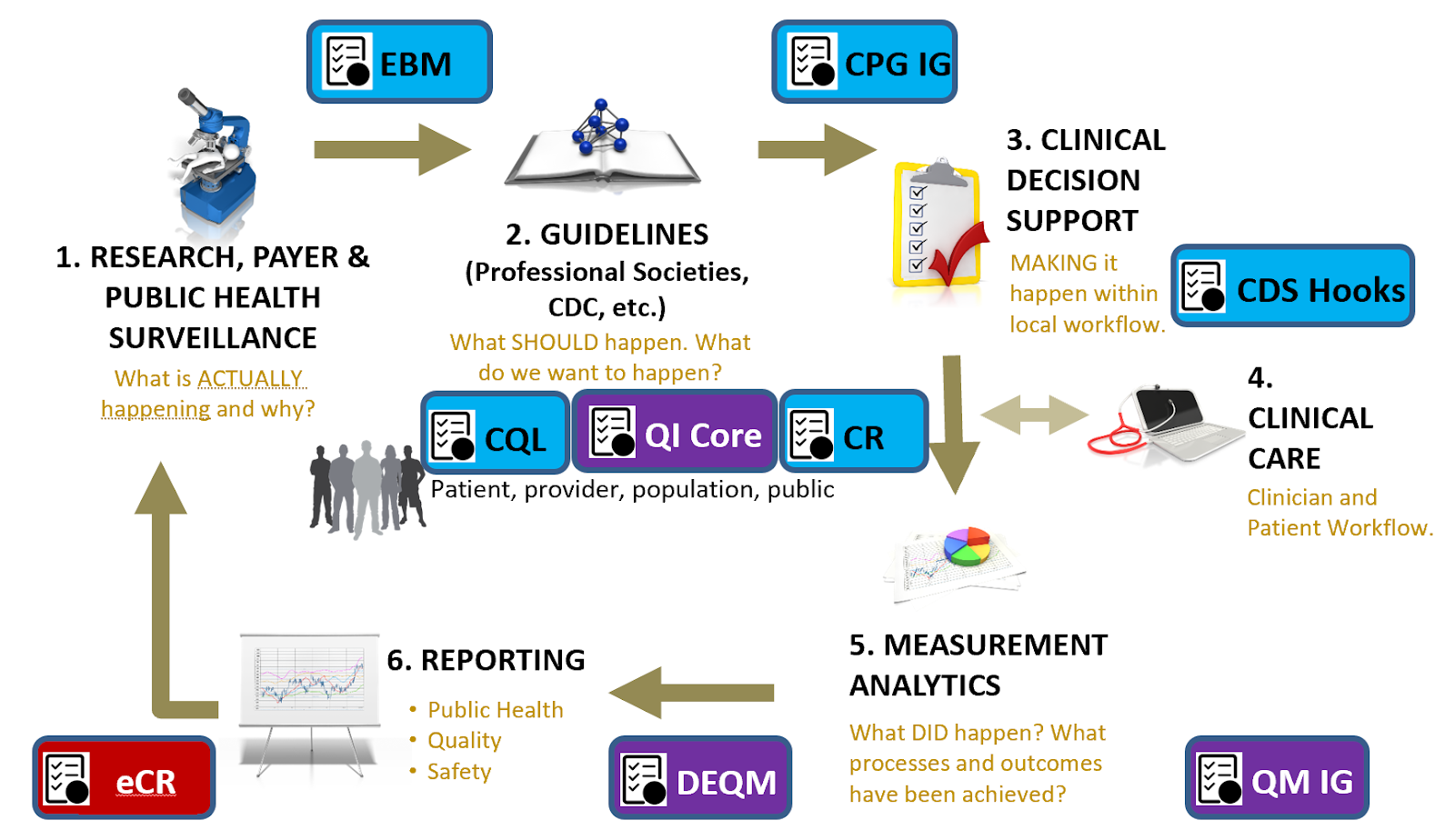

Figure 1.2 Clinical Quality Lifecycle with situated standards to address each respective phase. The CPG-IG addresses a critical gap in explicitly formalizing the guideline recommendations and other guideline features as computer-interpretable for downstream consumption and closing the feedback and feedforward loop(s).

Translating guideline recommendations and other types of guidance into practice has historically been a site by site exercise that has been disconnected from guideline/guidance development, creating unnecessary redundancies and introducing potential errors in translation that can lead to inconsistencies in how the guideline or guidance is executed. This clinical practice guidelines implementation guide (CPG-IG) consists of standards and a standardized, scalable approach to help make the effort of translating and implementing clinical practice guidelines and other types of guidance more efficient and effective. Key aspects include:

The purpose of the CPG-IG is to:

Direct goals:

Indirect goals:

The primary objective of the CPG approach to codifying clinical practice guidelines is to accelerate the translation and delivery of expert body evidence-based and best practice recommendations to the point of care. The CPG-IG was developed through multi-stakeholder engagement (e.g., guideline developers, knowledge engineers, clinical implementers, standards experts, patient and caregiver advocates, governmental and nongovernmental agencies, and others) to evolve the development approach and means of expressing clinical practice guidelines in computable formats. These stakeholders identified the need to concurrently develop computable formats along with the narrative guidelines/guidance. As such, the knowledge engineering process, inclusive of elicitation, translation, specification, and formal representation, must be integrated with the guideline development process and serve the function of translating between the clinical domain and the formal, computable expressions thereof. It is the intent of this section to describe some of the fundamentals of these activities as well as the concept, means, and performances to carry out this activity.

Secondarily, we describe how these activities interact with adjacent and related activities as well as content and related standards in the broader knowledge ecosystem (inclusive of evidence ecosystem, guideline developers, guideline-directed care, quality measure ecosystem, registry community, etc.). This includes upstream activities, such as evidence generation and knowledge discovery, and downstream activities, such decision support (i.e., CDS), patient care, advanced cognitive support (e.g., using SMART-on-FHIR apps), quality measurement and reporting, and electronic case reporting (for similarly scoped conditions). All can serve to inform subsequent iterations of clinical guidelines and guideline-directed care and thus have a key role in the learning health system.

This implementation guide provides both an approach and suggested methodology for computable representation of clinical practice guidelines, so the audience for this guide is broad and inclusive of an array of roles across the spectrum of clinical guideline development and implementation, from clinical guideline developers and authors, through clinical informaticists, health system integrators and clinical systems developers. Areas of the implementation guide that are more technical assume familiarity with relevant standards, including FHIR and Clinical Quality Language (CQL), though links are provided to reference materials for further reading.

Notes to Target Audiences:

The CPG Approach section highlights:

Much of this work has been informed by several international efforts, including the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Adapting Clinical Guidelines for the Digital Age initiative (ref), the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Antenatal Care Guidelines (ref), the HL7 Clinical Decision Support and Clinical Quality Information Working Groups, and numerous other publicly funded and private sector initiatives, including local health system implementations of guidelines and in-workflow pathways.

To the Guideline Developer: Working in parallel with knowledge engineers and other downstream consumers (e.g., local implementers) can identify areas within the guideline that need clarification, helping improve the narrative, provide opportunity to review the translation of the tools for fidelity to the guideline, and get early feedback from end-consumers of the guideline work product – all before the guidelines or tools are published.

To the Knowledge Engineer: Working in parallel with guideline developers allows validation of translations directly with the “source of truth,” helping ensure accuracy. Working in parallel with downstream consumers (e.g., local implementers) provides the ability to confirm feasibility and validity for the users of the artifacts as they are produced by knowledge engineers and may even provide a useful means to build and validate once (i.e., without unnecessary redundancy) against real-world data and implementations.

To the Downstream Consumers: Being involved with the guideline development and knowledge engineering can help identify issues early in the process and optimize incorporation of the knowledge into downstream products that aid in implementation, such as apps, measures, or other point-of-care tools, and significantly reduce the rework of re-engineering parts of the guideline, saving time and effort.

To the Local Implementer: The main goal of the knowledge developed is to implement it in practice. Having local implementers (both clinicians and informaticians) involved with guideline development and knowledge engineering allows for the ability to communicate anticipated issues for implementation so that guideline developers or knowledge engineers have the opportunity to adjust their respective products in order to help optimize the ease and positive impact of implementation. A computable guideline representation can significantly reduce rework, saving time and effort for local implementations.

To the Evidence Ecosystem: Taking a holistic approach to guideline development and implementation includes considerations for learning and continuous improvement through feedback and feedforward loops. A number of activities in the knowledge ecosystem that serve specific functions (e.g., case reporting to public health, quality reporting to payers, quality/data reporting to medical society registries, etc.) could also help provide the evidence that can inform updates to the guidelines/guidance. This evidence may be based on patient-level, point-of-care guideline usage, and detailed tracking thereof, affording new means of collecting evidence.

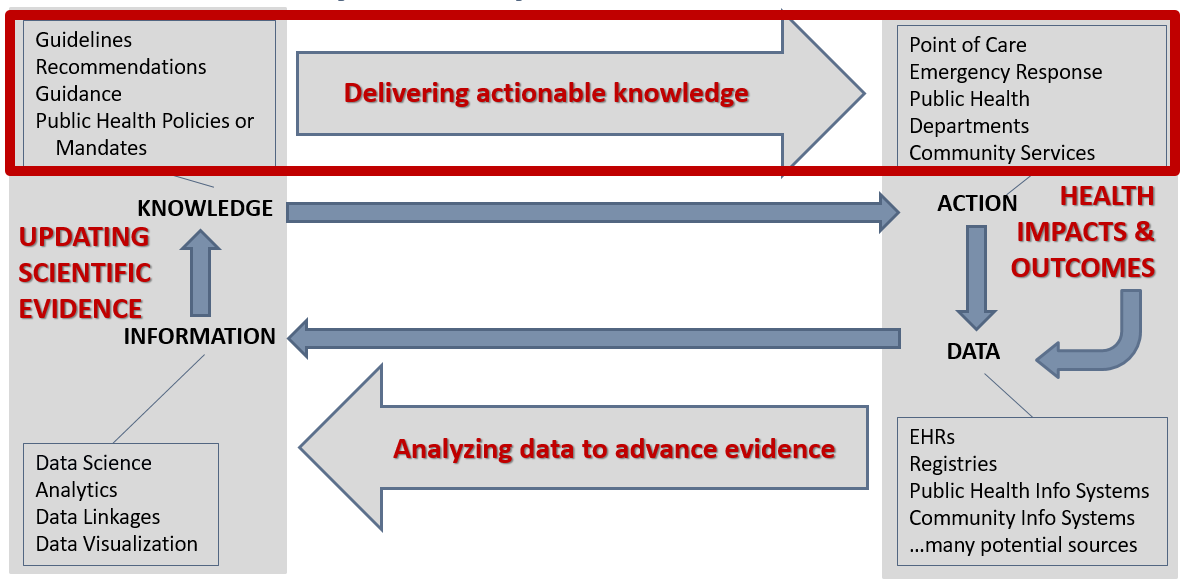

Using approaches, standards, and techniques addressed in further detail in individual sections, the CPG-on-FHIR as described in this implementation guide can serve a critical role in the full data lifecycle of a Learning Health System.

The need for computable care guidelines can be considered in the context of the data lifecycle, where the representation of the guideline recommendations in FHIR helps deliver actionable knowledge (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.3 The data lifecycle and impacts to the public’s health (Michaels, M, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019).

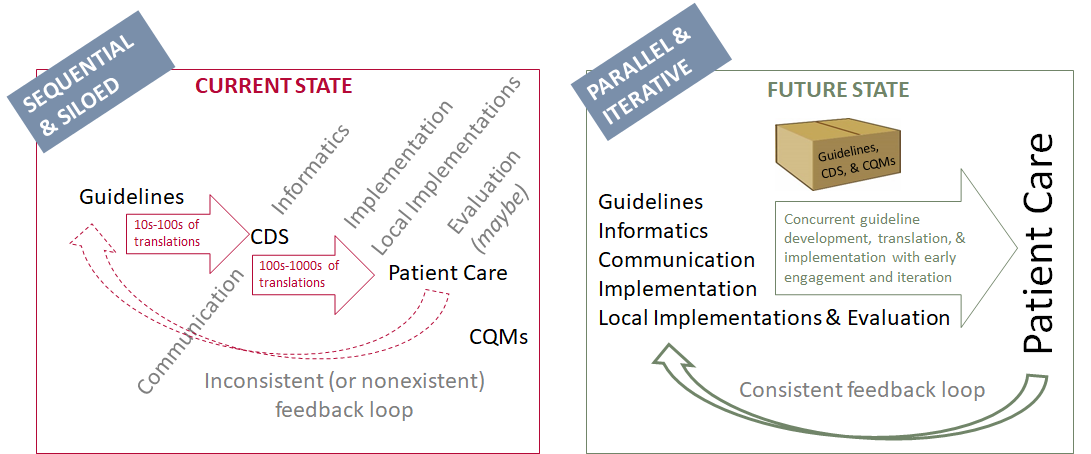

By translating the recommendations in clinical practice guidelines at the source, and disseminating a computable version along with the narrative version of the guidelines, the effort of translation would not be repeated across every organization that intends to apply the recommendations. Likewise, unnecessary or unintentional variations as a result of duplicative translation efforts could be prevented with a standard, computable version that is ready to be implemented. In removing the need for translating recommendations at each local clinical system, and removing as much variation as possible through a standard translation, the time needed to apply the recommendations in practice should also be reduced, helping scientific evidence reach patient care more easily, quickly, accurately, and consistently.

In considering common patterns across multiple guidelines, this implementation guide can apply to a variety of use cases across multiple clinical domains, as is evidenced by the examples provided. These common patterns not only create a way to organize the content for the translation into computable recommendations but also help implementers operationalize the recommendations within clinical workflows.

Figure 1.4 Redesigning guideline development and implementation: The Integrated Process (Michaels, M, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019). NOTE: The “Implementation” perspective represents local implementers that incorporate the local considerations into guideline translations, and “Local Implementations” represent the actual implementation at clinical sites.

In particular, the translation into tools like CDS and eCQMs applies common health IT standards like Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) and Clinical Quality Language (CQL). How to use these standards to develop shareable, platform-independent tools based on guidelines/guidance for a variety of diseases, conditions, or preventive care is the primary focus of this CPG-IG, including this Approach section. Secondarily, this CPG-IG shows how using FHIR can help with other data-focused activities, such as public health reporting (i.e., using electronic case reports) or quality reporting (i.e., using eCQMs), that provide a feedback loop that feeds the evidence. The evidence can also be represented using FHIR (i.e., EBM-on-FHIR) and could be applied in summarizing evidence and updating guidelines/guidance. This completes the “data lifecycle” that allows for continuous learning and improvement – a “learning health system”. The CPG-IG approach can be a key component of a learning health system in times requiring rapid response, where knowledge of best practice is not well-known.

It is important to note that this effort is a concerted attempt to build on, learn from, contribute to, and work with existing approaches, initiatives, and efforts in guideline development, translation, and implementation. The contribution of this implementation guide is focused on describing a best-practices conceptual approach combined with a practical methodology that leverages the interoperability framework provided by FHIR as a way to overcome the impedance mismatch between knowledge and clinical data models that is commonly encountered by efforts in this space. The approach and methodologies presented here are the combined result of many person years of work across multiple initiatives and coordinated with groups like Health eDecisions, Clinical Quality Framework initiative, the CDC's Adapting Clinical Guidelines for the Digital Age intiative, the Object Management Group's BPM+ for Health initiative, IHE's Computable Care Guidelines initiative, and the WHO's Smart Guidelines initiative. Feedback on the approach and methodologies are welcomed and encouraged. See the references section for further reading and background that informs the approach taken here.

| Author Name | Affiliation | Role |

|---|---|---|

| Sivaram Arabandi, MD, MS | Ontopro LLC | Contributor |

| J. Rex Astles, PhD, FAACC | CDC, Health Scientist | Contributor |

| Wendy Blumenthal, MPH | CDC, Health Scientist | Contributor |

| Mike Boston | UX Architect | Contributor |

| Matthew M. Burton, MD | Apervita, Inc., VP Clinical Informatics | Editor |

| Zahid Butt MD, FACG | Medisolv Inc, CEO | Contributor |

| Dave Carlson, PhD | Clinical Cloud Solutions, Solution Architect | Contributor |

| Daryl Chertcoff | HLN Consulting, Solution Architect | Contributor |

| Jeffrey Danford, MS | Allscripts, Sr Principal Software Engineer | Contributor |

| Floyd Eisenberg, MD, MPH | iParsimony | Contributor, Co-Chair (Clinical Quality Information) |

| Margaret S. Filios, MSc, BSN, RN, CAPT USPHS | CDC, Senior Scientist | Contributor |

| Daniel Futerman | Jembi Health Systems, Senior Program Manager | Contributor |

| Joel C. Harder, MBA | AiCPG, Executive Director | Contributor |

| Aaron M. Harris, MD, MPH, FACP | CDC, Subject Matter Expert | Contributor |

| Dwayne Hoelscher, DNP, RN-BC, CPHIMS | Nursing Informaticist | Contributor |

| Emma Jones RN-BC, MSN | Allscripts, Expert Business Analyst | Contributor, Co-Chair (Patient Care), IHE Co-Chair (Patient Care Coordination) |

| James Kariuki | CDC, Health Scientist | Contributor |

| Kensaku Kawamoto, MD, PhD, MHS | Contributor, Co-Chair (Clinical Decision Support) | |

| Robert Lario, MSE, MBA | University of Utah/US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Standards Architect | Contributor |

| Ira M. Lubin, PhD | CDC, Health Scientist | Contributor |

| Laura Haak Marcial | RTI International, Health Informaticist | Contributor |

| Robert McClure, MD, MPH | Contributor, Co-Chair (Vocabulary) | |

| Maria Michaels | CDC | Editor |

| Blackford Middleton, MD, MPH, MSc, FACP, FACMI, FHIMSS, FIAHSI | Apervita, Chief Informatics & Innovation Officer | Contributor |

| Nikhil Patel MBBS, BSc | NHS, Physician | Contributor |

| Bryn Rhodes | Dynamic Content Group | Editor, Co-Chair (Clinical Decision Support) |

| Derek Ritz | ecGroup Inc., Principal Consultant | Contributor, IHE Co-Chair (Quality Reporting and Public Health) |

| Susan J. Robinson, PhD | CDC, Senior Advisor | Contributor |

| Julie Scherer, PhD | Motive Medical Intelligence, Chief Informatics Officer | Contributor |

| Julia Skapik | Cognitive Medical Systems, CHIO | Contributor |

| Larie Smoyer, MD | Motive Medical Intelligence, VP of Product Development | Contributor |

| Davide Sottara, PhD | Mayo Clinic | Contributor |

| Keith Toussaint | KMT Strategies, Principal | Contributor |

| Jodi Wachs MD, FAAPM&R FAMIA | Clinical Informaticist | Contributor |

| David Winters | The MITRE Corporation | Contributor |

RxNorm: This product uses publicly available data courtesy of the U.S. National Library of Medicine (NLM), National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services; NLM is not responsible for the product and does not endorse or recommend this or any other product.

Nelson SJ, Zeng K, Kilbourne J, Powell T, Moore R. Normalized names for clinical drugs: RxNorm at 6 years.

J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011 Jul-Aug;18(4)441-8. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000116.

Epub 2011 Apr 21. PubMed PMID: 21515544; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3128404.

Full text

UCUM: This product includes all or a portion of the UCUM table, UCUM codes, and UCUM definitions or is derived from it, subject to a license from Regenstrief Institute, Inc. and The UCUM Organization. Your use of the UCUM table, UCUM codes, UCUM definitions also is subject to this license, a copy of which is available at http://unitsofmeasure.org. The current complete UCUM table, UCUM Specification are available for download at http://unitsofmeasure.org. The UCUM table and UCUM codes are copyright © 1995-2009, Regenstrief Institute, Inc. and the Unified Codes for Units of Measures (UCUM) Organization. All rights reserved.

THE UCUM TABLE (IN ALL FORMATS), UCUM DEFINITIONS, AND SPECIFICATION ARE PROVIDED "AS IS." ANY EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES ARE DISCLAIMED, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY AND FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE.