This page is part of the Da Vinci Risk Adjustment FHIR Implementation Guide (v0.1.0: STU 1 Ballot 1) based on FHIR (HL7® FHIR® Standard) R4. The current version which supersedes this version is 2.1.0. For a full list of available versions, see the Directory of published versions

The Da Vinci Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resource (FHIR) Risk Adjustment Implementation Guide describes exchanging risk adjustment coding gaps between payers and providers. Risk adjusted premium calculations are important to government managed care. To better inform providers of opportunities to address risk adjusted conditions, better enable payers to communicate risk adjustment information, and enhance government sponsors’ ability to allocate funding accurately, payers and providers need a standard protocol to share and receive clinical data related to risk adjustment and a standard methodology to communicate risk based coding, documentation and submission status of chronic conditions. This first release of this implementation guide focuses on the standard exchange format of risk adjustment coding gaps from payers to providers.

This implementation guide is supported by the Da Vinci initiative which is a private effort to accelerate the adoption of Health Level Seven International Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (HL7® FHIR®) as the standard to support and integrate value-based care (VBC) data exchange across communities. Like all Da Vinci Implementation Guides, it follows the HL7 Da Vinci Guiding Principles for exchange of patient health information. As an HL7 FHIR Implementation Guide, changes to this specification are managed by the sponsoring Clinical Quality Information (CQI) Work Group and are incorporated as part of the standard balloting process.

This implementation guide is divided into several pages which are listed at the top of each page in the menu bar:

Home: The home page provides the summary, background information, scope, and actors for this implementation guide.

Guidance: The guidance page provides guidance on the resource profiles and operation defined in this implementation guide.

FHIR Artifacts/Profiles: This page lists the set of Profiles that are defined in this implementation guide to exchange risk adjustment coding gaps.

FHIR Artifacts/Extensions: This page lists the set of Extensions that are defined in this implementation guide to exchange risk adjustment coding gaps.

FHIR Artifacts/Operations: This page lists operations defined in this implementation guide.

FHIR Artifacts/Terminology: This page lists code systems and value sets defined in this implementation guide.

FHIR Artifacts/Capability statements: This page describes the expected FHIR capabilities of the risk adjustment actors of this implementation guide.

Examples: List of all the examples used in this implementation guide.

Glossary/Acronyms: List of acronyms for this implementation guide.

Glossary/Glossary: List of glossary for this implementation guide.

Downloads: This page provides links to downloadable artifacts.

Health risk is a combination of two factors, loss and probability. Many players in the healthcare industry need to measure and manage health risk. For example, providers need to know which patients in their panel are facing the greatest clinical risks to prioritize their care; insurance payers need to know the expected financial risk of their covered lives so they can price their premiums appropriately.

Risk adjustment models are used to compare and normalize health risks across groups or populations. For instance, the Medicare Advantage (MA) population represents a risk pool, as does the subset of the MA population that Payer X covers. One common use of risk adjustment is to make equitable comparisons among healthcare payers that take into account the health status of their enrolled members, to provide adequate financial support for treating individuals with higher-than-average health needs, and to minimize incentives for plans and providers to selectively enroll healthier members. Risk adjustment models determine whether Payer X’s risk pool represents more or less health risk than the MA population average, so that if Payer X is running a greater risk – say, because its risk pool includes a greater portion of economically disadvantaged persons – then appropriate payments are made to help ensure that these member’s premiums are subsidized to offset the higher expected cost of claims that Payer X will incur. Risk adjustment is used for this purpose within Medicare (the CMS-HCC1 and CMS-RxHCC1 models), Medicaid (the CDPS1 and MRX1 models), the Affordable Care Act (the CMS-HCC and RXC1 models), as well as other health insurance programs.

Risk prediction models have a different intent. These are used to predict the future behavior of individuals or populations such as who is likely to be a high utilizer of healthcare services or who is likely to experience adverse health care events.

This IG has mainly focused on the Medicare Advantage risk adjustment models, but it should also work for other risk adjustment and prediction models as long as they structure their data using Condition Categories (CC). A CC is a clinically or financially related grouping of medical conditions. The number of CCs in each risk model depends on the purpose of that model, from about 80 CCs in the CMS-HCC model to about 400 CCs in the DxCG1 model. It is very common for CCs to be organized in terms of disease hierarchies and disease categories, with the former denoting the severity of a disease and the latter indicating other aspects such as which system and/or part of the anatomy is affected, how the disease affects the body, the nature of the disease process, what causes it, how it spreads, how quickly it progresses and so forth. When a disease hierarchy is applied it changes CCs into Hierarchical Condition Categories (HCCs) with less severe HCCs superseded (ignored) if evidence of higher severity HCCs is present.

This IG focuses on risk adjustment for revenue normalization, but risk adjustment has several other applications. Quality measures such as Plan All-Cause Readmissions, Acute Hospital Utilization, Hospitalization Following Discharge from a Skilled Nursing Facility, Emergency Department Utilization and Hospitalization for Potentially Preventable Complications are all risk-adjusted. Risk adjustment is used in care management to identify future high-cost or high-utilizing individuals, direct them toward appropriate treatment options, allocate resources for that treatment, and evaluate the outcomes of those programs. Risk adjustment is also used as an analytical method by actuaries and underwriters for pricing purposes. However, the goals, processes and methods of these other risk adjustment applications are quite different from those of risk adjustment for revenue normalization and are outside the scope of this IG.

Unless otherwise specified, when the term “risk adjustment” is used in this IG it is limited to risk adjustment for revenue normalization and is exclusively concerned with the exchange of diagnostic data to resolve CC or HCC gaps.

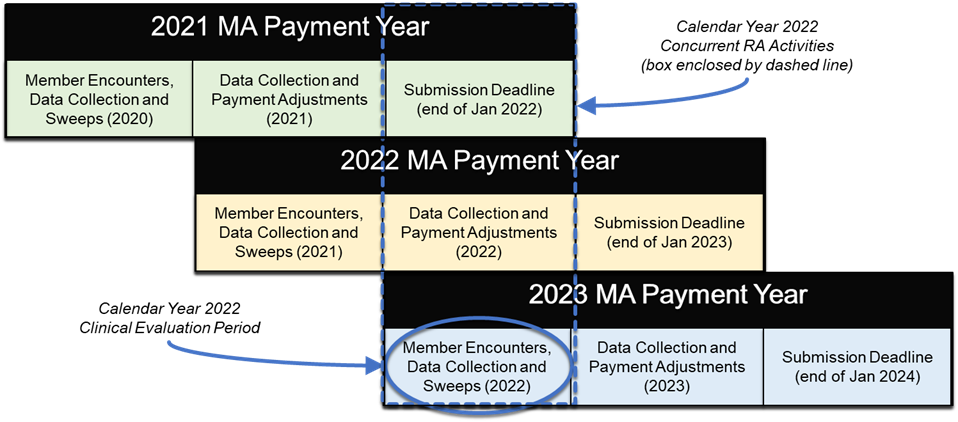

The date of service for the extracted diagnosis must correspond to the correct Payment Year but payers are generally permitted more than one calendar year to collect the diagnoses. There are several important time periods to keep track of here. For example, the Medicare Advantage clinical evaluation period runs from January 1 of [PY-1] through December 31 of [PY-1] during which the patient may have encounter(s) with provider(s) to document the presence of disease(s). The Medicare Advantage data collection period runs from January 1 [PY-1] to the end of January [PY+1]; during this time the payer may submit diagnoses collected during the clinical evaluation period to CMS. PY denotes the Payment Year, or the year when the payer receives it payment adjustment from Medicare. These payments begin on January 1 of [PY] based on diagnoses submitted to CMS through the first week of September of [PY-1]. This is a particularly important date known as the September Sweeps. For financial reasons, payers want to submit as many diagnoses as they can prior to September Sweeps because these are used to set the amount for the initial payment adjustments. Payers sometimes offer providers “Early Bird” incentives to document HCCs as soon in the year as they can, preferably prior to September Sweeps. For this reason, it is important for the payer to record when they receive medical evidence that closes an HCC gap so the provider can receive any “Early Bird” incentives they may have earned.

For example, during Medicare Advantage PY 2022 diagnoses are accepted from patient encounters with dates of service during the clinical evaluation period of Jan 1, 2021 to Dec 31, 2021. Payers may submit to Medicare the diagnoses they collect from these encounters as soon as Jan 1, 2021 and continuing through the end of Jan 2023. Sweeps for PY 2022 occur at the end of the first week of Sep 2021. Payers begin receiving payment adjustments from Medicare beginning in Jan 2022 based on diagnoses received through Sweeps.

The risk adjustment activities in support of these payment cycles concurrently overlap during any given year, as shown in the Figure 1-1. Note that this figure shows the Medicare Advantage risk adjustment cadence; other programs such as Medicaid and the ACA follow a different annual risk adjustment cadence.

Since the data collection period is always longer than the clinical evaluation period there will be multiple models actively collecting data at the same time. For example, during the calendar year 2022 a typical MA payer will be actively collecting data to close gaps from several models:

To avoid confusion, the Client supplies dates for the clinical evaluation period, which is driven by dates of service. So if the Client sets the clinical evaluation period to run from Jan 1, 2022 through Dec 31, 2022, the Server would only report CC gaps from these models:

What’s going on with these three different model versions? There are three answers.

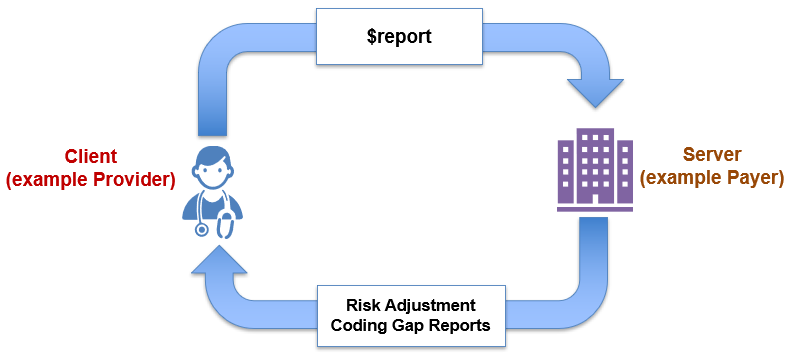

After careful review with the risk adjustment subject matter experts, it was determined that the most challenging aspect of the current risk adjustment process was the inconsistent manner in which reports on risk adjustment coding gaps were communicated between a provider (or system operating on their behalf) and a payer (or system operating on the payer’s behalf). Figure 2-2 shows a high level example of the risk adjustment workflow in CMS Medicare advantage program. This version of the implementation guide focuses on specifying a standard exchange format, the Risk Adjustment Coding Gap Report, from payers to providers.

This implementation guide does not define how payers determine a coding gap and how coding gaps are produced or managed on the payer side including hierarchies. This implementation guide also does not define suspecting processes and algorithms/predictive models that are used for suspecting analytics. It is the intent of this implementation guide to expand its specifications in future versions to support communication of coding gaps from providers back to the payers, for example to provide a mechanism to allow providers to communicate HCC invalidations to payers.

The actors involved in exchanging risk adjustment coding gap reports are Clients and Servers.

As shown in Figure 1-3, the Client calls the $report operation that is defined in this IG, the Server then queries matching Risk Adjustment Coding Gap Reports based on the parameters provided in the operation and returns the reports to the Client.

This implementation guide was made possible by the thoughtful contributions of the following people and organizations: