This page is part of the Clinical Guidelines (v2.0.0: STU2) based on FHIR (HL7® FHIR® Standard) R4. This is the current published version. For a full list of available versions, see the Directory of published versions

CPG Methodology- Using the Integrated Process, Agile KE, and BPM+ for ACEP’s COVID-19 ED Severity Classification and Disposition Recommendations

During 2020, a coalition of nearly fifty private sector organizations, including healthcare delivery organizations (e.g. hospital systems) formed to advance the rapid development and dissemination of computable clinical best practice guidance for COVID-19. The coalition tackled the need for classifying COVID-19 patients presenting in emergency room settings to inform recommendations for triaging patients to differing levels of care and settings.

Members of the team were drawn from CDC’s Adapting Clinical Guidelines for the Digital Age initiative, where work was ongoing prior to the pandemic to coordinate and manage the development of standards-based computable guideline representations using the HL-7 FHIR framework and corresponding lifecycle development processes, documented in this overall implementation guide.

The resulting COVID-19 Digital Guideline Working Group (C19 DGWG) organized into functional teams as follows:

In addition, consultation was received on Knowledge Architecture (HL7 standards) from the HL7 CDS Work Group, Informatics Sub-Group).

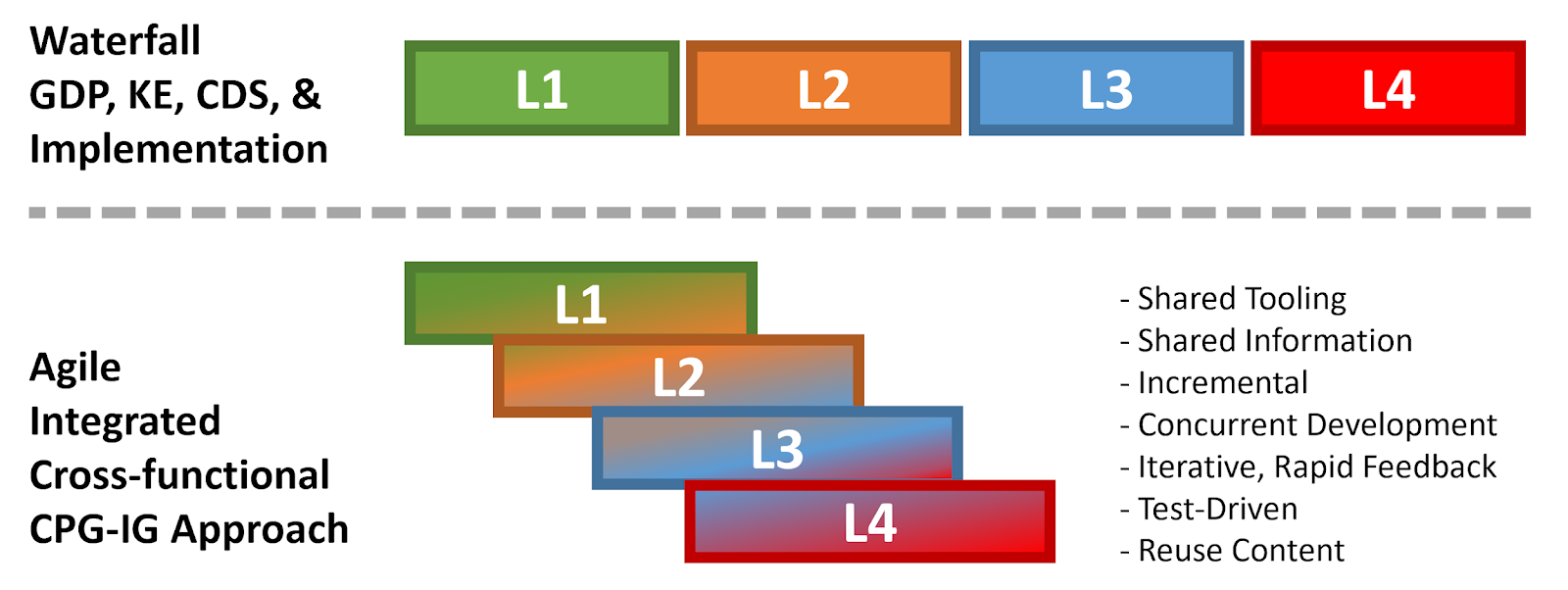

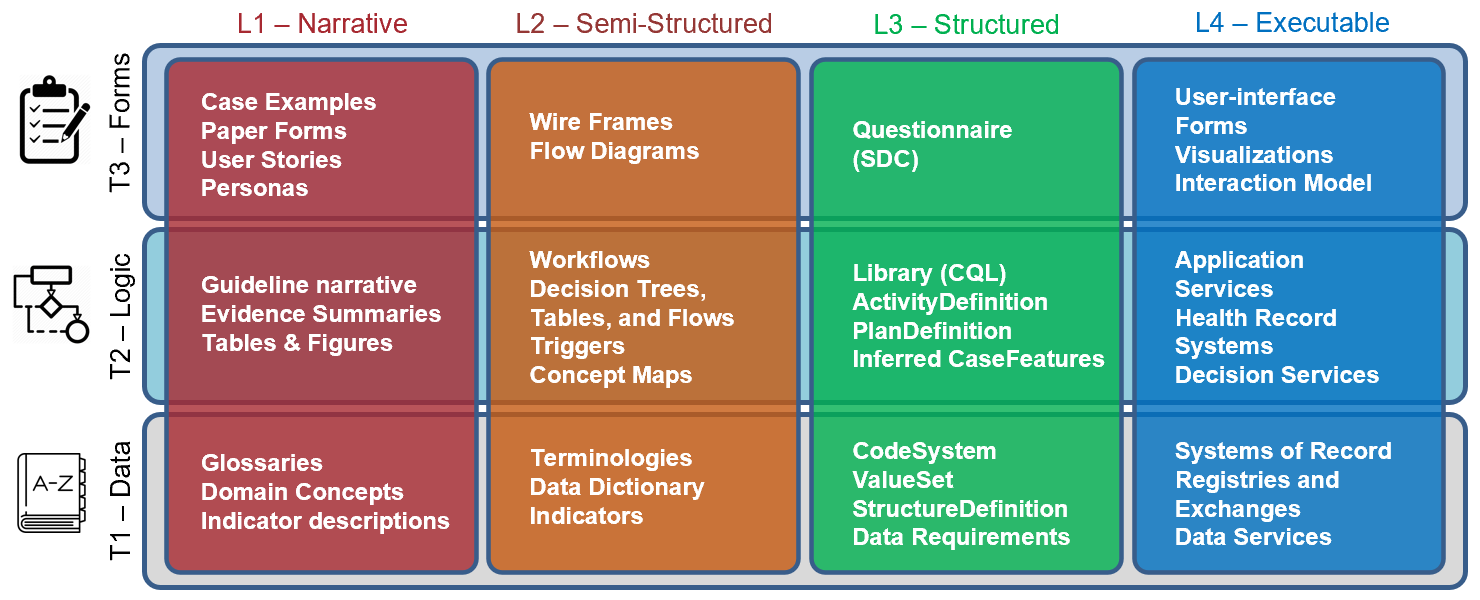

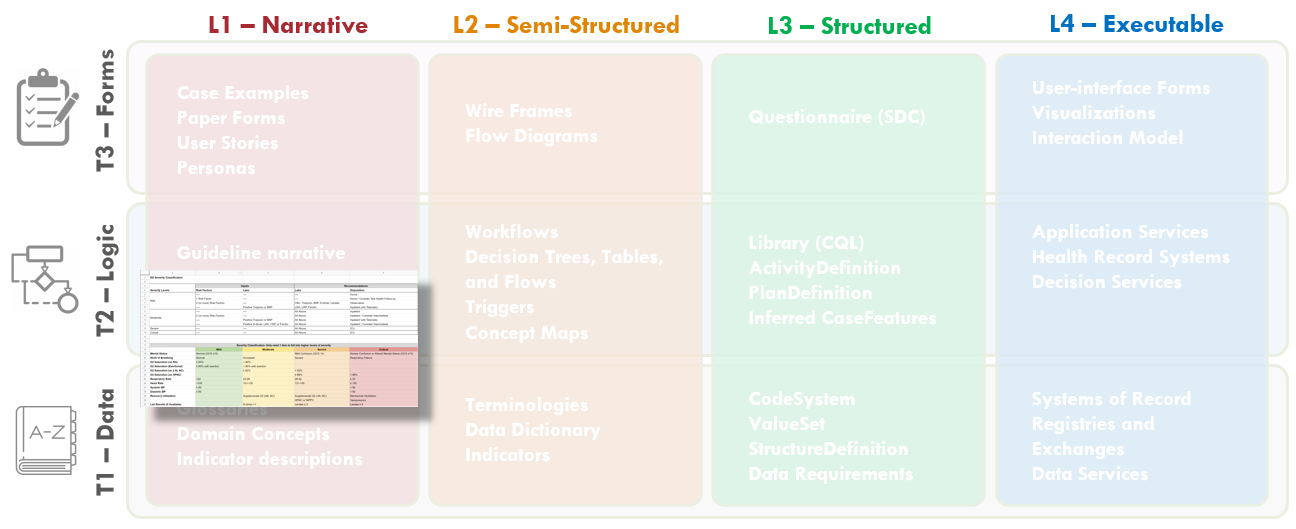

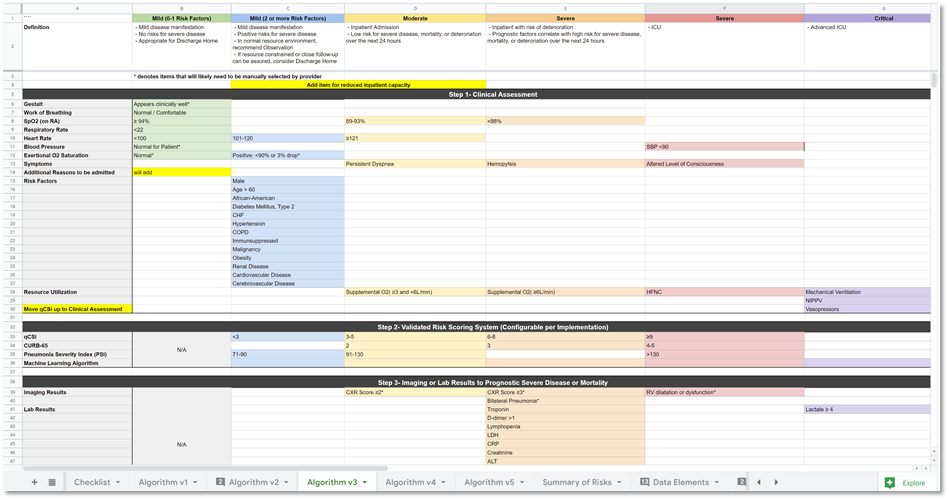

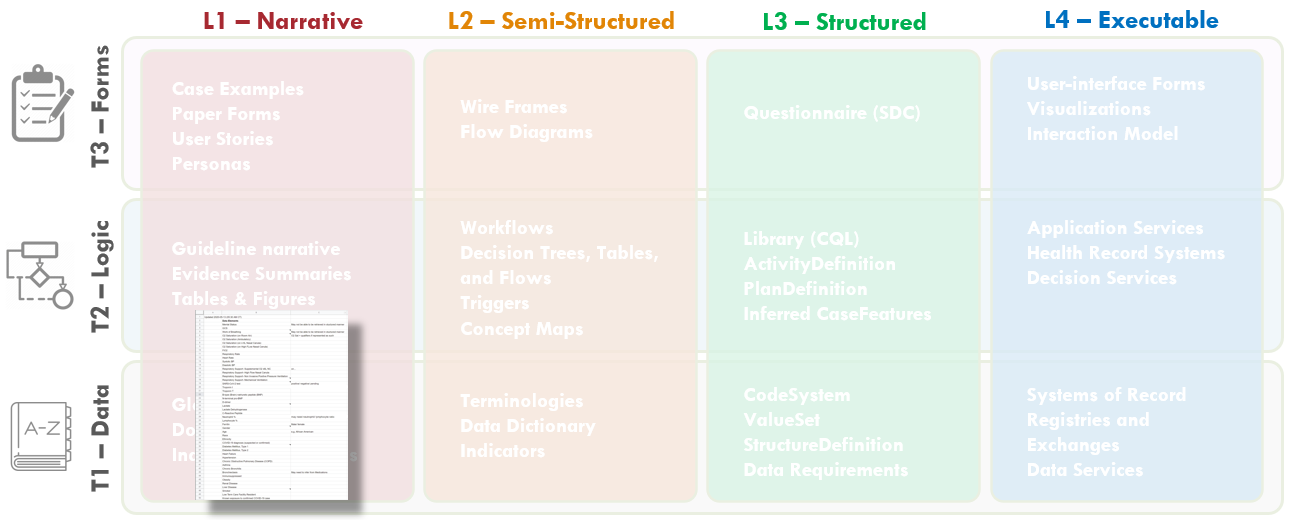

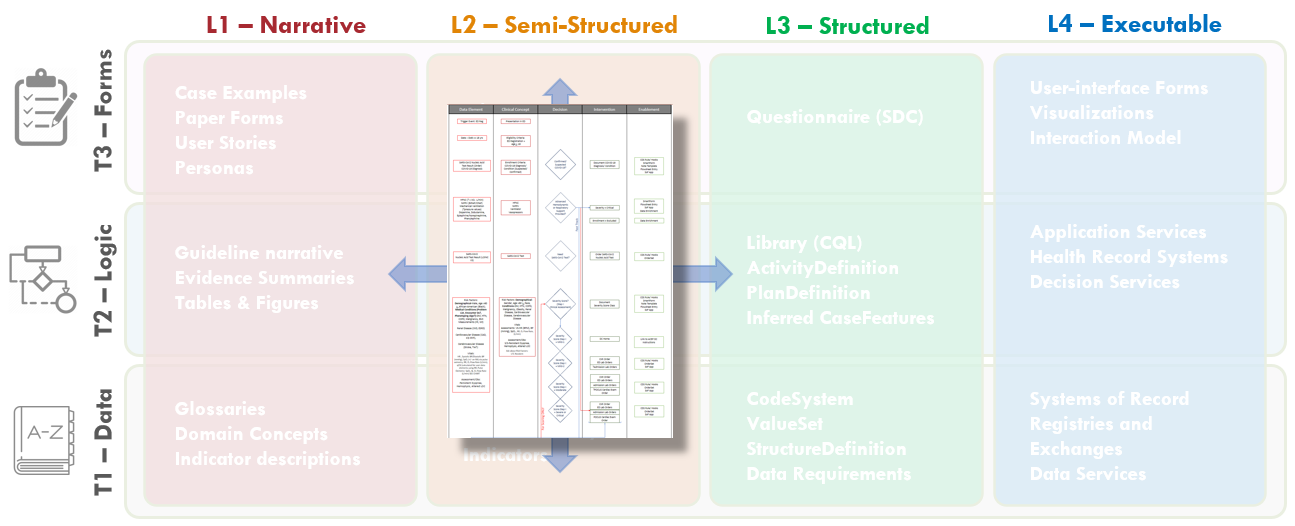

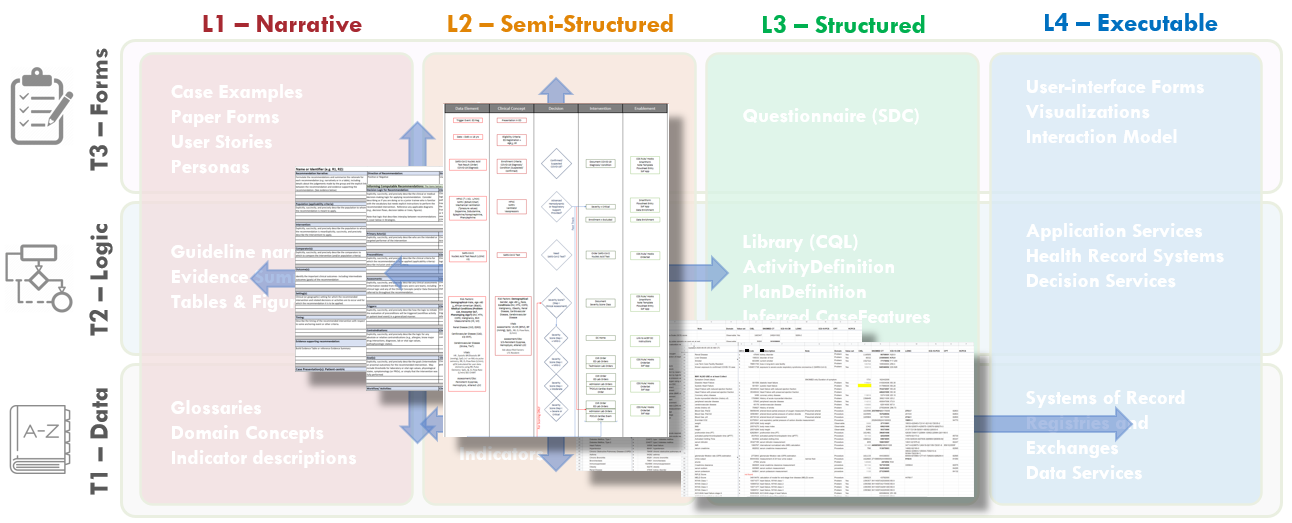

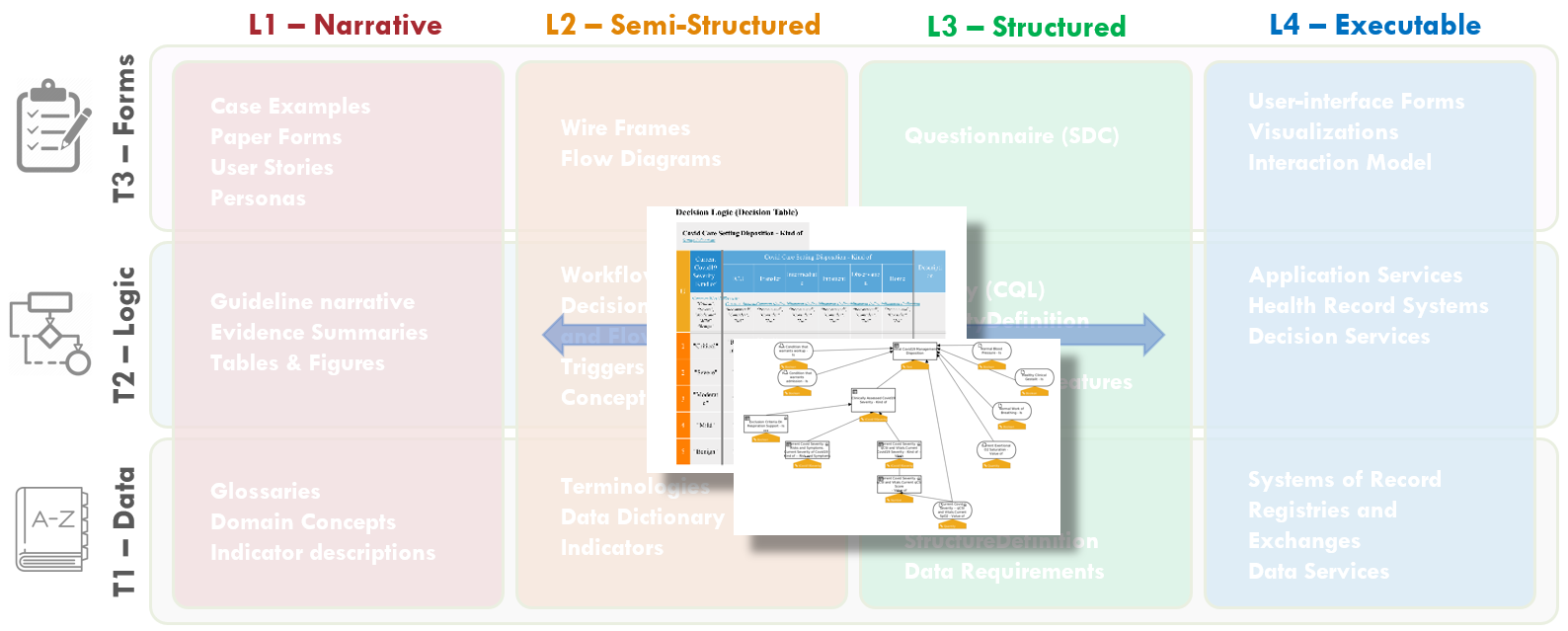

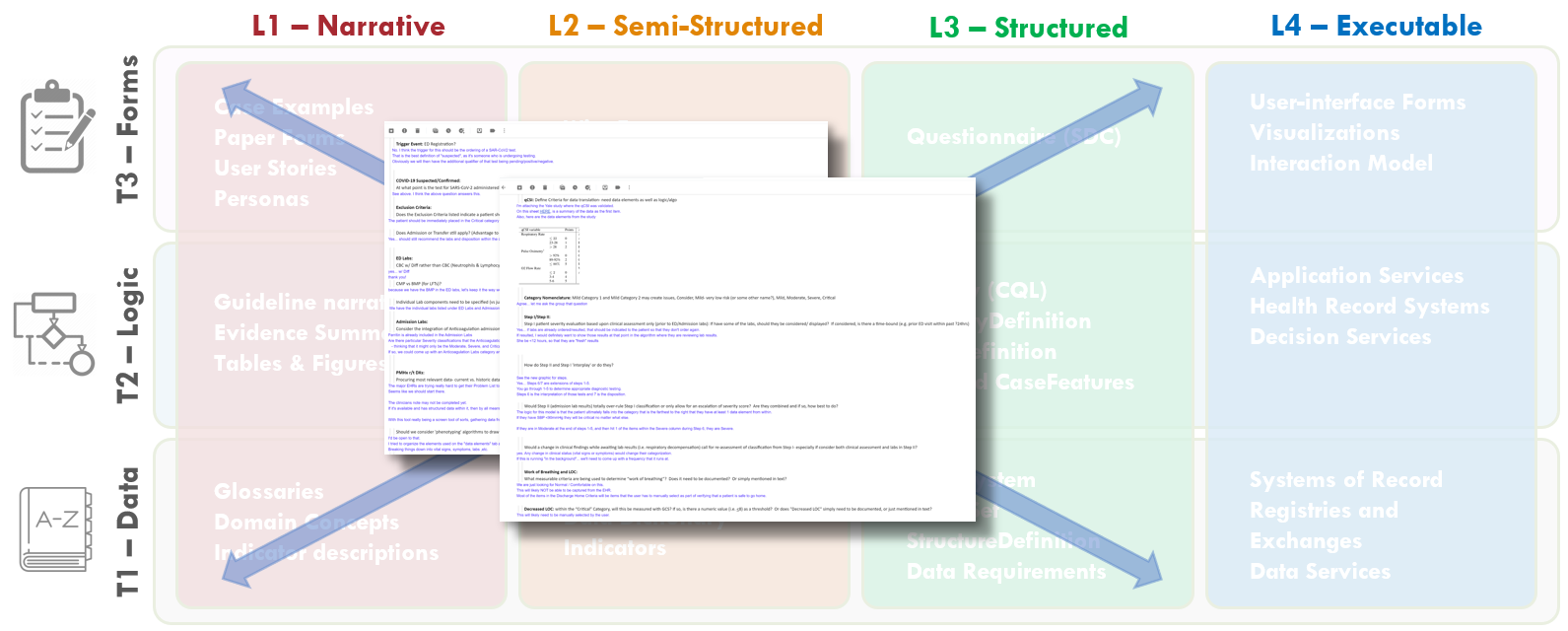

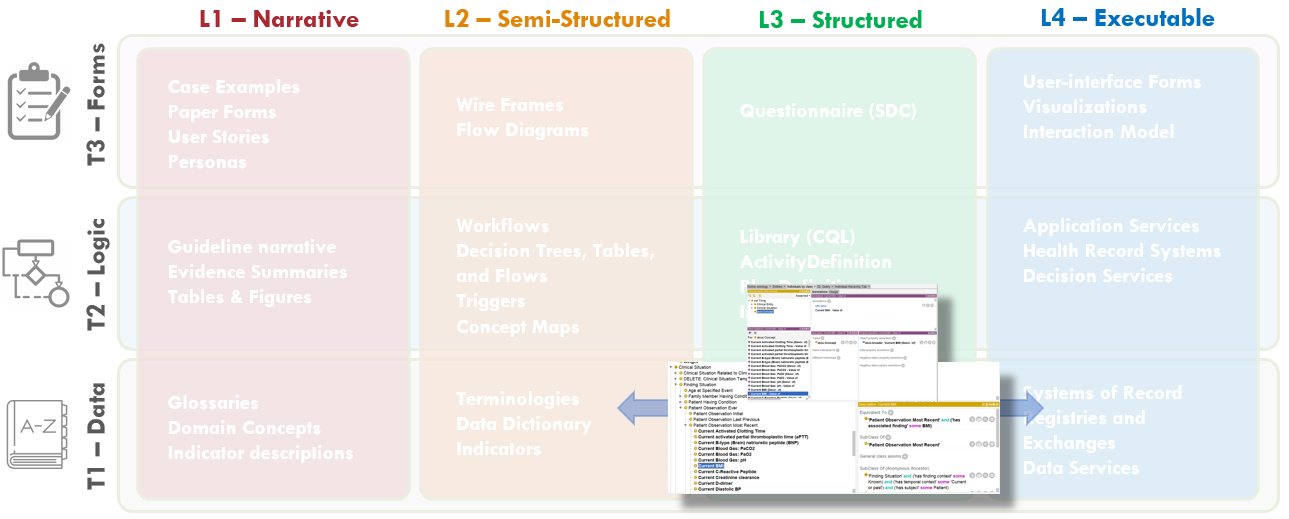

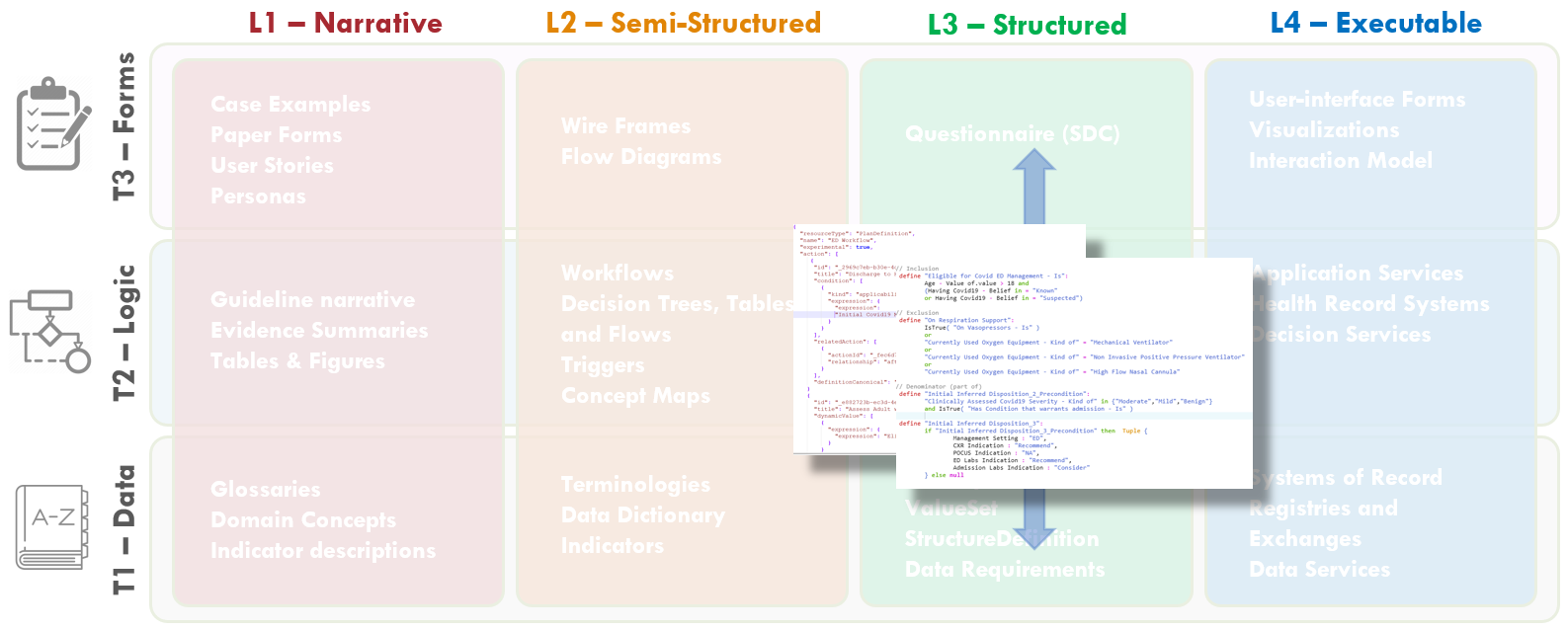

Members of the content team, which included f \rontline clinicians, clinical informaticians, and representatives from medical specialty professional societies and evidence-based practice centers (EPCs) provided content in the form of high-level use cases and detailed clinical domain knowledge. The knowledge engineering team worked with the content team to review and prioritize the content. Next, an integrated, cross-functional Agile CPG Team was formed for each use case consisting of members from each of the functional teams. The work was performed using the Integrated Process and Agile Approach to CPG Development resulting in L1-L4 artifacts as shown in Figure MSC.01, as outlined in this implementation guide,.

Figure MSC.01. The Agile Approach to CPG Development using Agile Knowledge Engineering principles and practices including concurrent, iterative, and incremental development of all Levels of Representation by an integrated, cross functional team.

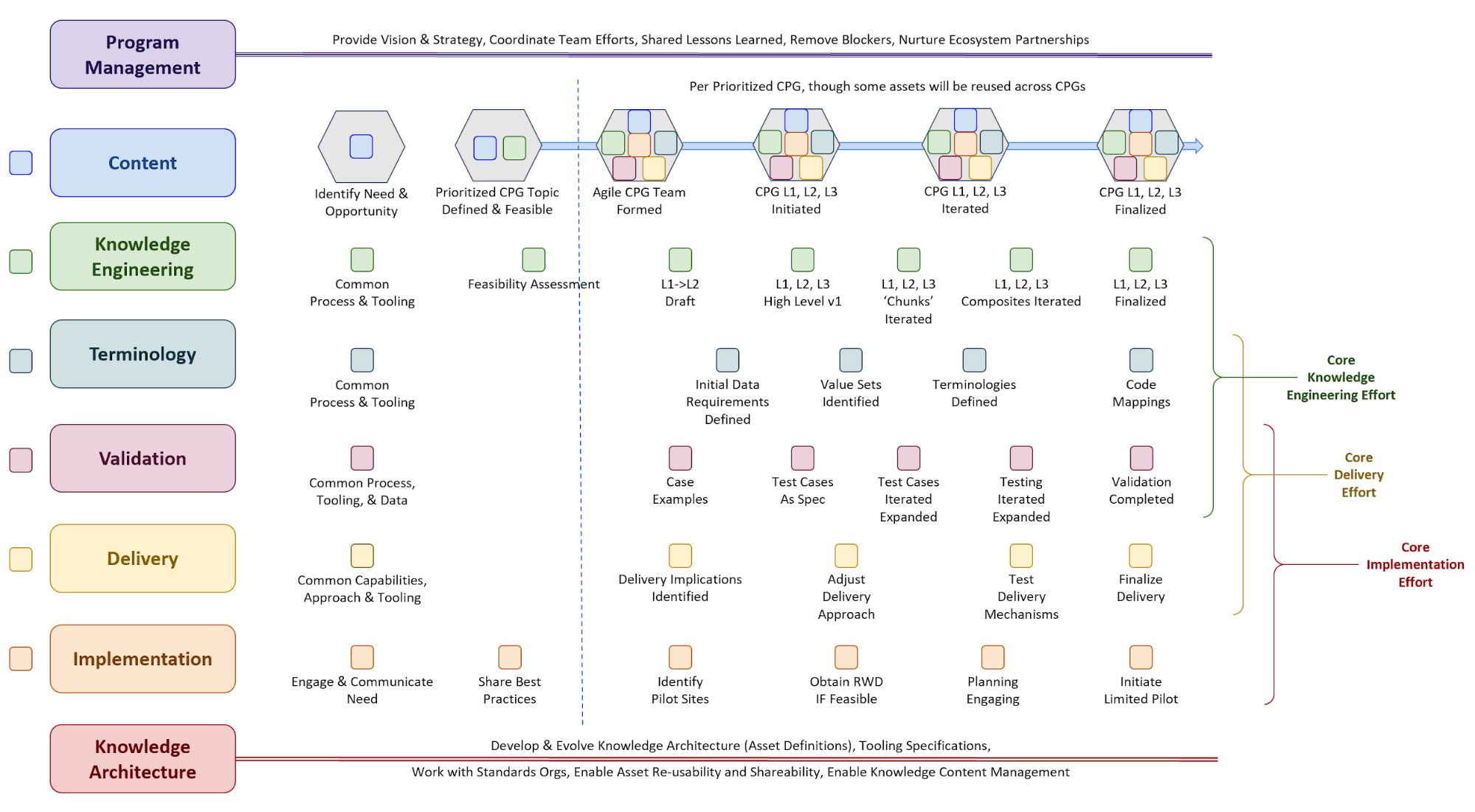

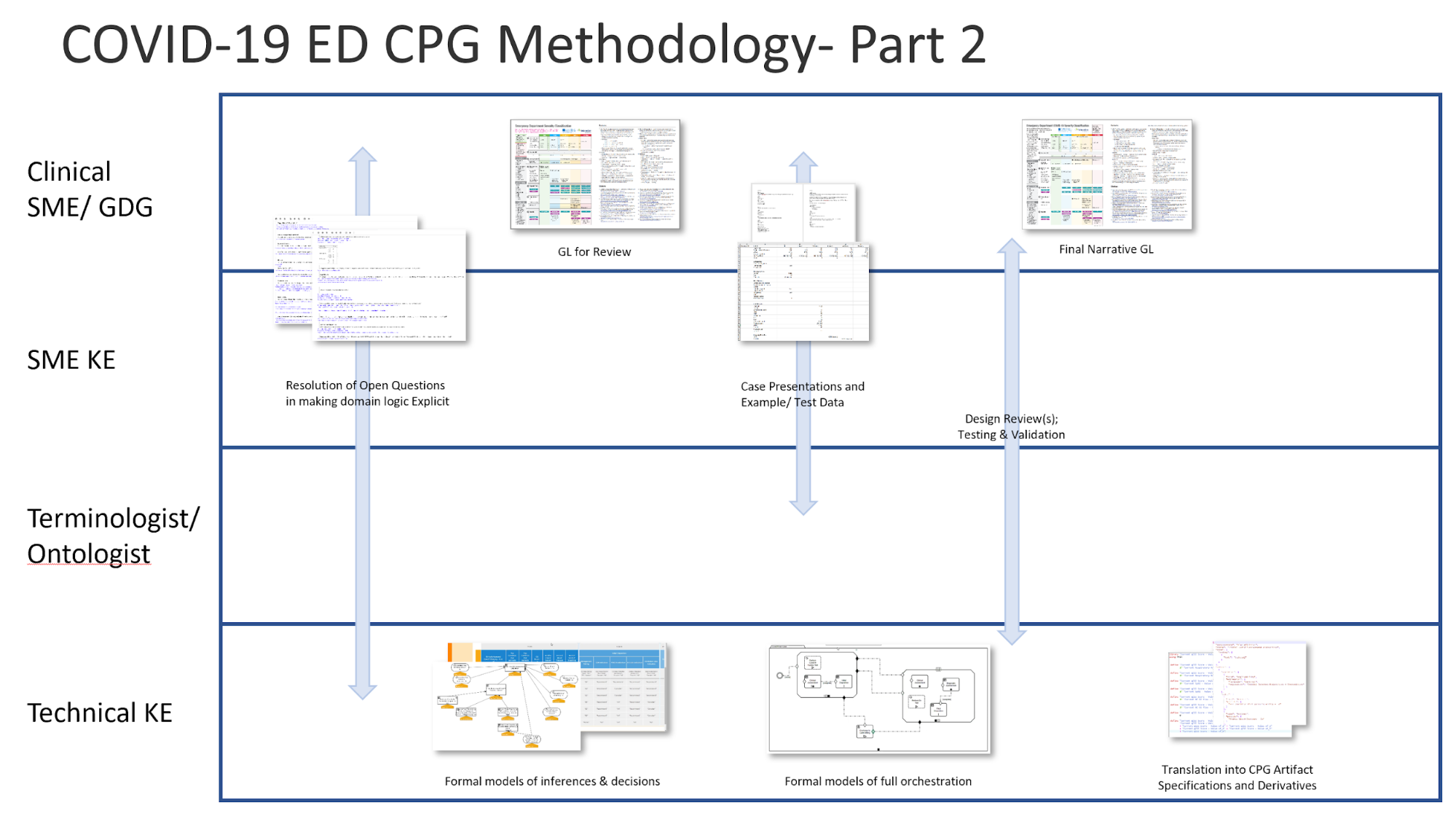

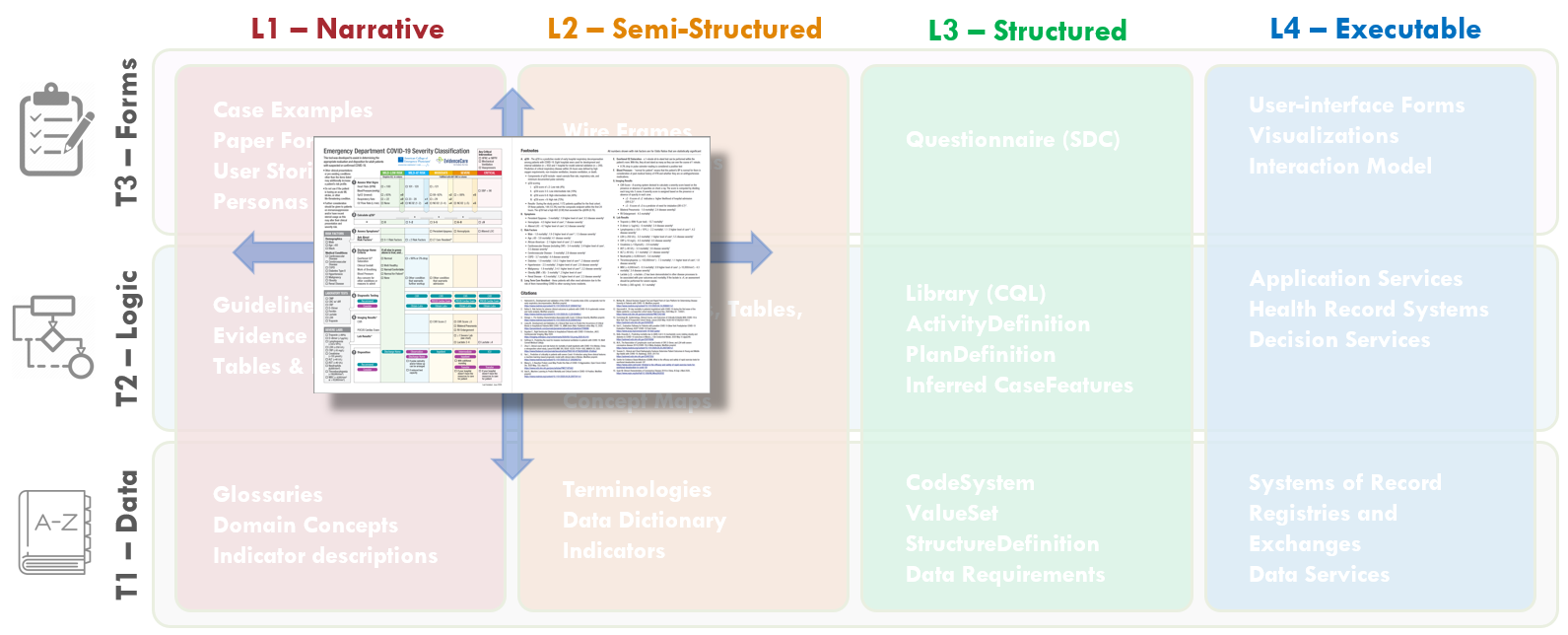

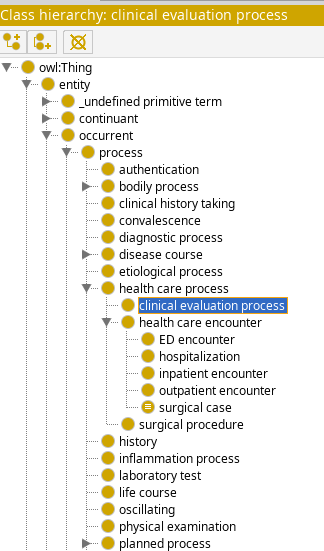

Figure MSC.02 illustrates the high-level work activities and outputs tied to L1-L4, and which functional teams worked on these activities and outputs.

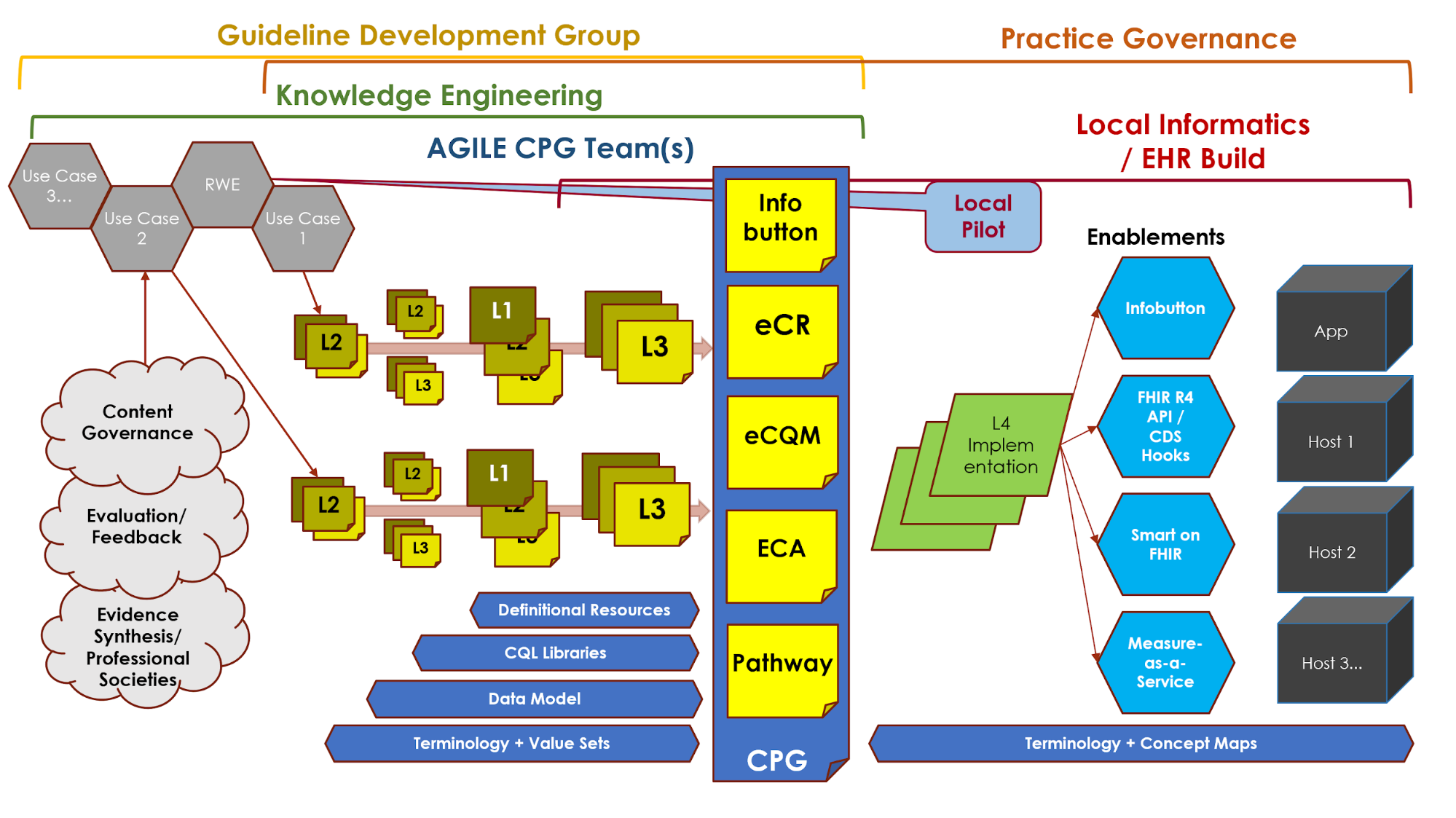

Figure MSC.03 illustrates the full life-cycle anticipated by the team, from development to implementation.

Methodology WorkFlow and Artifacts

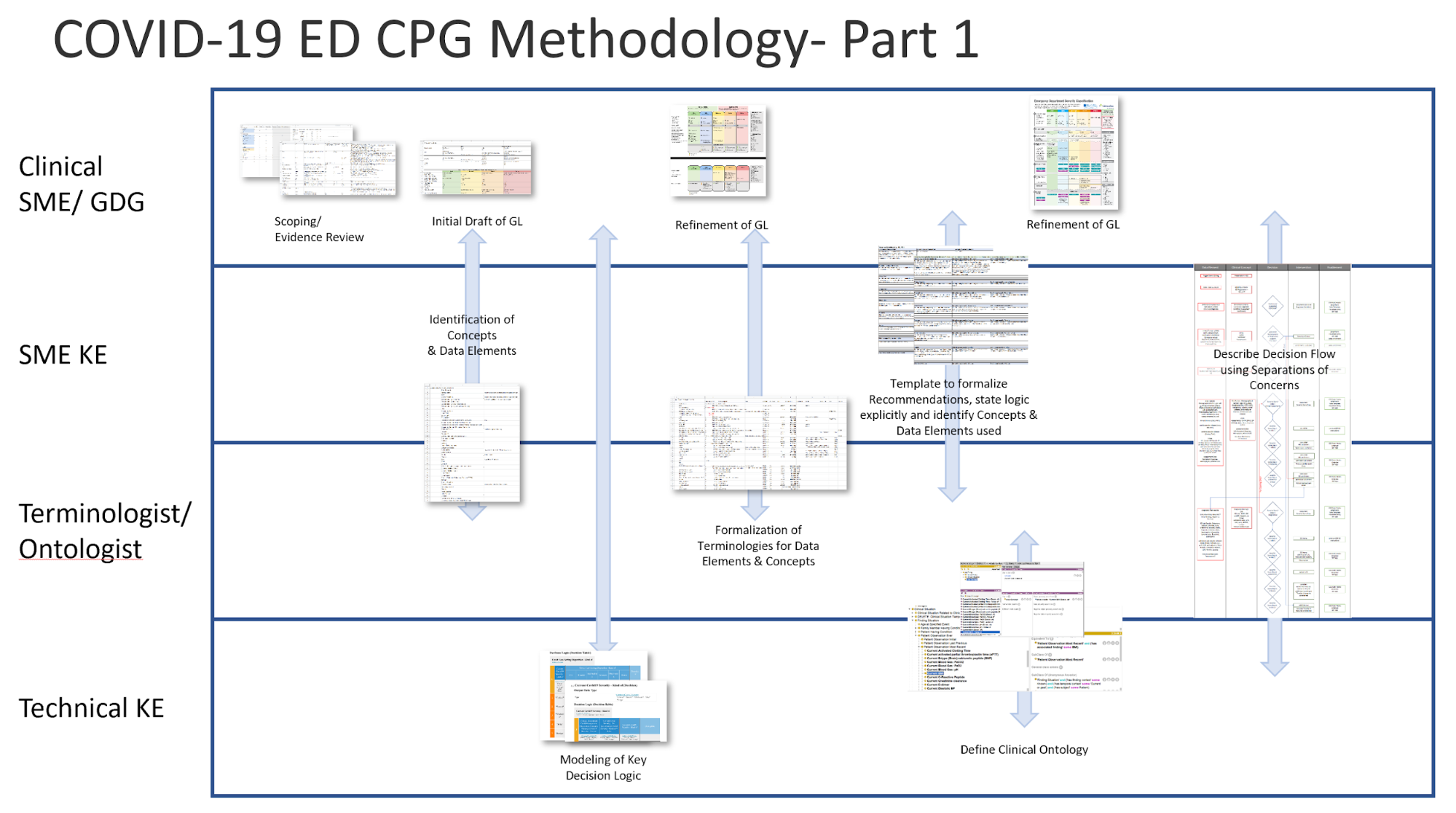

Figure MSC.03 provides a visual overview of the CPG methodology and the interactions between the different teams and disciplines during the rapid execution of the CPG methodology (broken out into Part 1 & 2 due to formatting limitations). An in-depth description of the process will reference the artifacts shown in this visual overview.

Figure MSC.04 Interdisciplinary integration: “Swim Lanes” in enacting the Agile Approach to CPG development methodology gives an overview of the work products and artifacts produced during execution of this methodology.

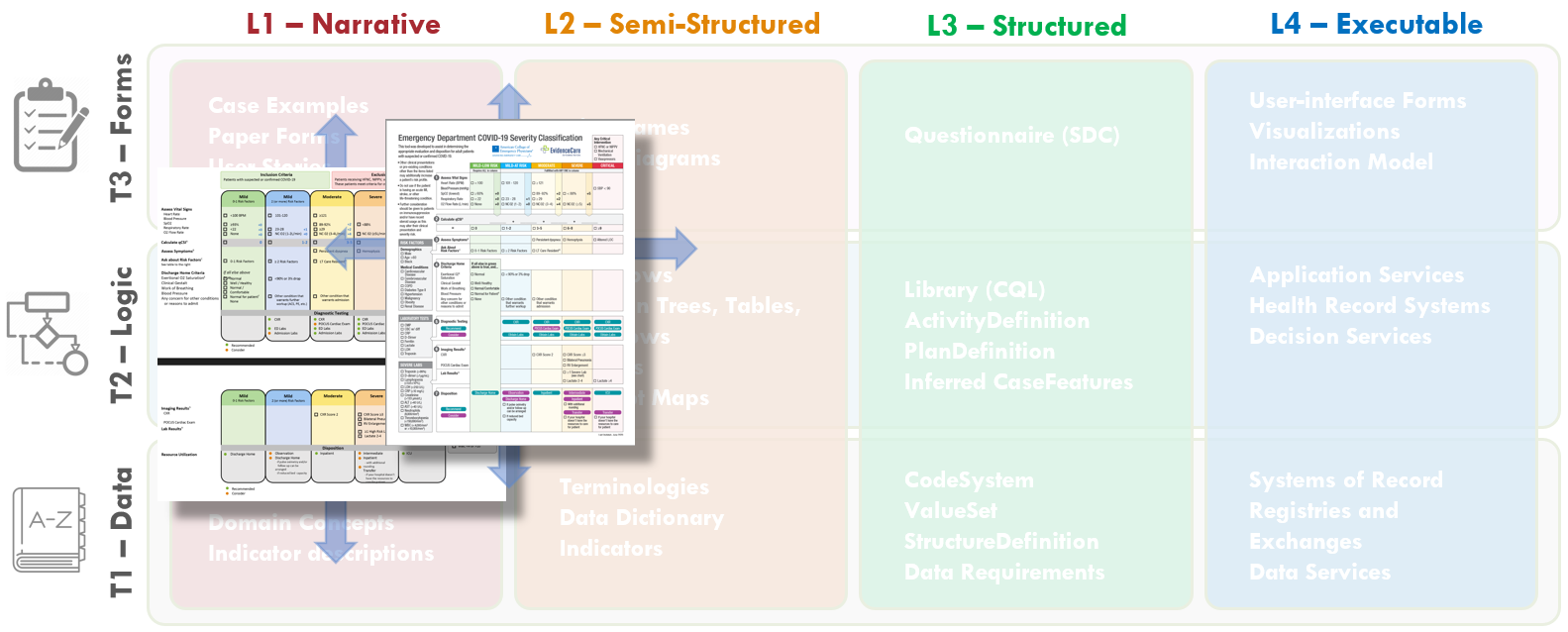

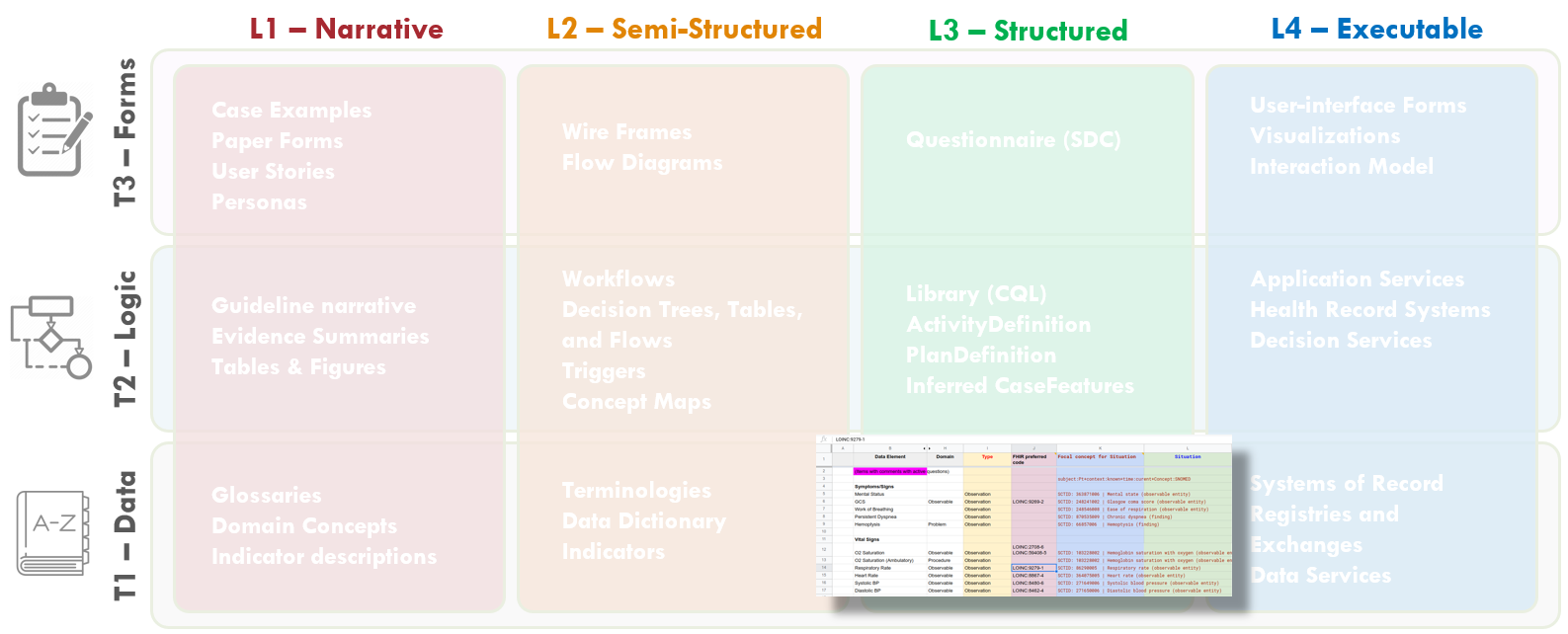

FIG MSC.05. Work products and artifacts produced during execution of the CPG methodology will be mapped to the Levels by TiersTable to illustrate where they are situated in the Knowledge Translation spectrum as well as where they serve to span this translation.

This section provides details how the clinical best practice guidance developed by the content team and their partners was translated into knowledge representations and expressions (FHIR Profiles), roughly following the process presented in this implementation guide. These details include more information on the activities, the various tools and methods used, and the artifacts and outputs produced by the team.

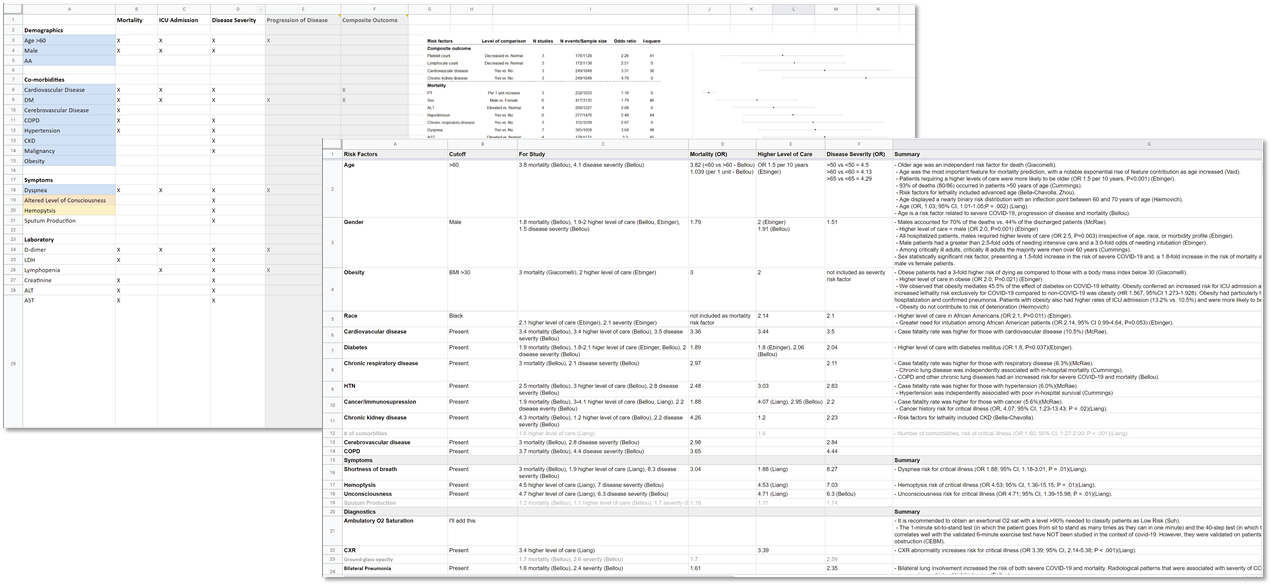

Scoping/Evidence Review Tool

FIG MSC.06 Scoping/review tool

The committee met on a weekly cadence for approximately 8 weeks as evidence was curated, the approach and format for the use case was formalized, and teams were assigned tasks to complete prior to the next meetings. To bring such a diverse group of stakeholders together and have them agree upon guiding principles and distill such disparate evidence into a concise recommendation so quickly was unusual, but warranted by the emerging pandemic.

NOTE: At the time of the writing of this CPG methodology example (November 2020), the content team was still meeting and working on updates to use cases, based on anticipated developments during the northern hemisphere flu season.

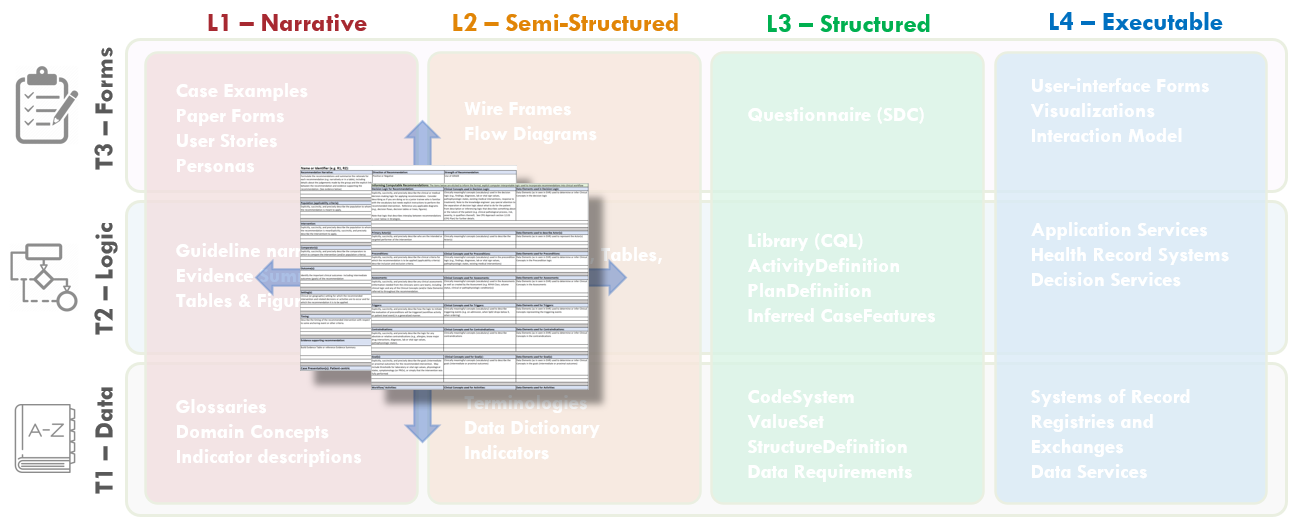

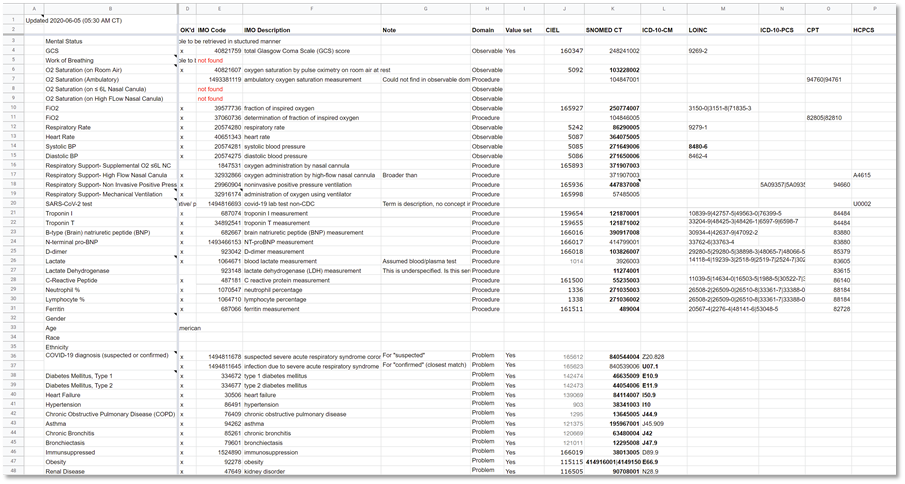

FIG MSC.07. The initial Draft of the COVID-19 ED Severity Classification and Disposition Recommendations is clearly Level 1, but addresses some specification around both Logic and Data.

The guidance development team (content) decided to represent the guidance in the form of a two-step evaluation, which would inform a five-level classification of disease severity and risk of poor outcomes.This format was chosen considering the need to make the score readability available and easy to perform by frontline clinicians (initially- most likely without the aid of automated computation). Together with the low level of evidence, It was decided to simplify the scoring and subsequent recommendations to a five-level, non-overlapping set of severity classifications.

GUIDANCE

Step 1: Perform a clinical assessment for initial severity classification and determination of further diagnostics. The clinical assessment itself consisted of vital sign values, the quick severity index (qCSI) based thereon, and an assessment of signs and symptoms as well as risk factors for developing severe COVID-19 disease or risk for poor outcomes.

Step 2: For patients with the four most severe classifications, the recommendation was to order an escalating set of diagnostics (labs, imaging, functional assessments). For the least severe classification, confirm patient to be low risk and disposition to home with follow-up via home and/or telehealth with monitoring.

The results of diagnostics or findings further informed the overall COVID-19 severity classification. Of note, the clinical assessment was to be continued up to disposition and could escalate the severity classification at any point, thus influencing further diagnostic testing and/or disposition. Thus, the clinical assessment is not merely a once-and-done assessment, but changing as a result of continual patient monitoring, additional diagnostics, and interventions. Thus the patients’ pathophysiology and clinical actions should be represented as a series of states.

For the scope of the emergency medicine practice, the classification could only be escalated, not de-escalated during the patient’s course of care in the emergency setting. A “Fast Track” to the Critical Severity Classification with disposition to ICU was identified and recommended for patients who required respiratory interventions (e.g., high flow nasal cannula, non-invasive positive pressure ventilation, mechanical ventilation) and/or hemodynamic support (e.g., vasopressors).

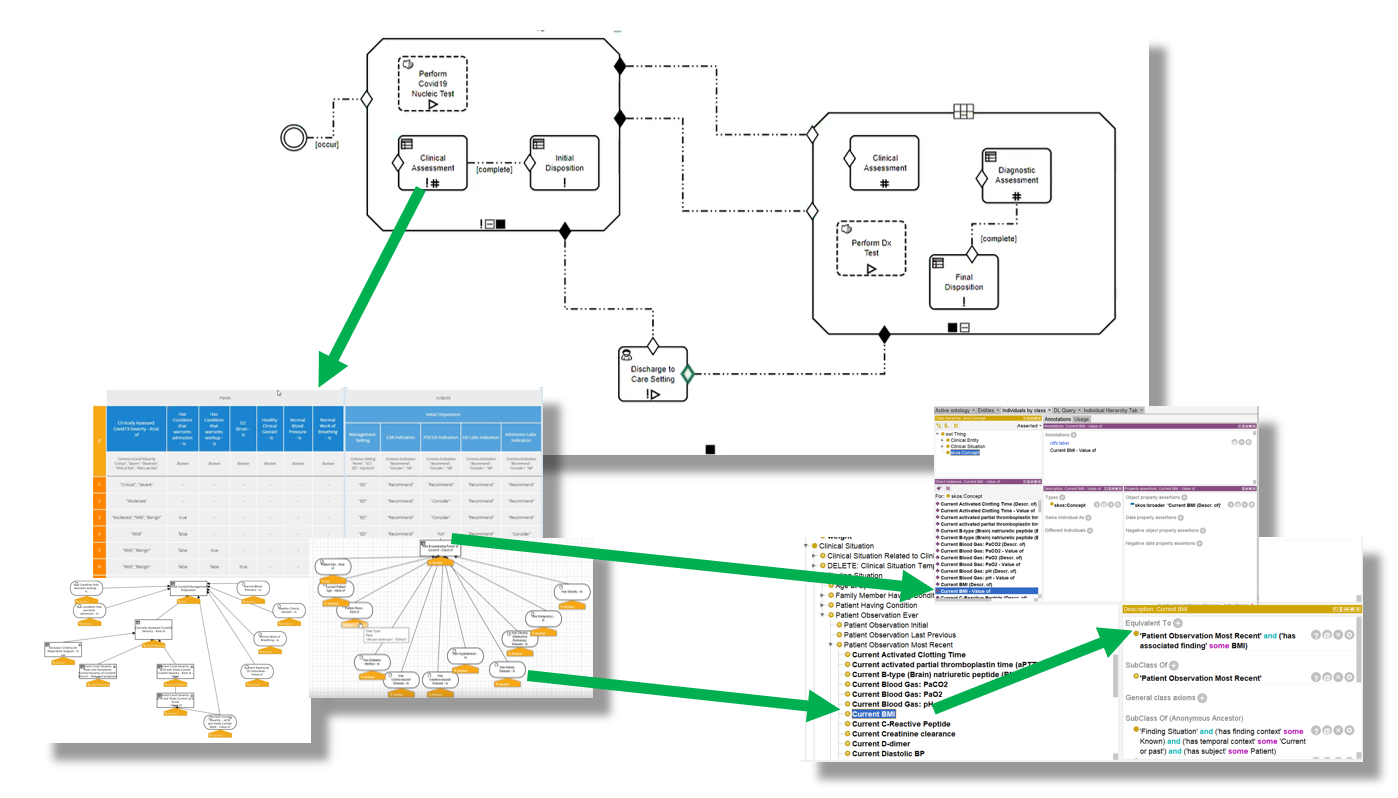

Figure. MSC.08. Initial draft of the Severity Classification and Disposition Guidance.

The diagnostic assessment included a constellation of laboratory tests (blood levels of key metabolites and proteins as well as blood cell cytology), chest radiology (CXR), and point-of-care cardiac ultrasound (POCUS). Results from these diagnostics could further be indicative of severe disease and/or poor outcomes and therefore could escalate the ED COVID-19 Severity CLassification and Disposition Recommendations.

The disposition recommendations are driven by the overall ED COVID-19 severity classification, which as noted above is continually informed by a potentially evolving clinical assessment and resulting diagnostic assessment, that are holistically monitored and assessed up to patient disposition to the next, appropriate care setting.

The American College of Emergency Medicine’s (ACEP) Guidance on: COVID-19 ED Severity Classification and Disposition Recommendations can be found here and the PDF is found here .

Notes: The COVID-19 severity classification developed takes into account both current disease severity as well as risk for developing severe disease or having poor outcomes and would ideally be modeled as a Risk-Severity Matrix in the future.

The clinical or SME knowledge engineers (SME KE) actively participated in many of the guideline development conversations and reviewed even the earliest drafts of the evidence reviews and initial iterations of the severity classification and recommendations. In an iterative and incremental fashion, SME KE elicited structured and more explicit information related to the severity classification and disposition recommendations, decision logic, and high-level implications for clinical workflow, the orchestration and decision logic for the strategies, and overall pathway and captured this knowledge in a structured template.

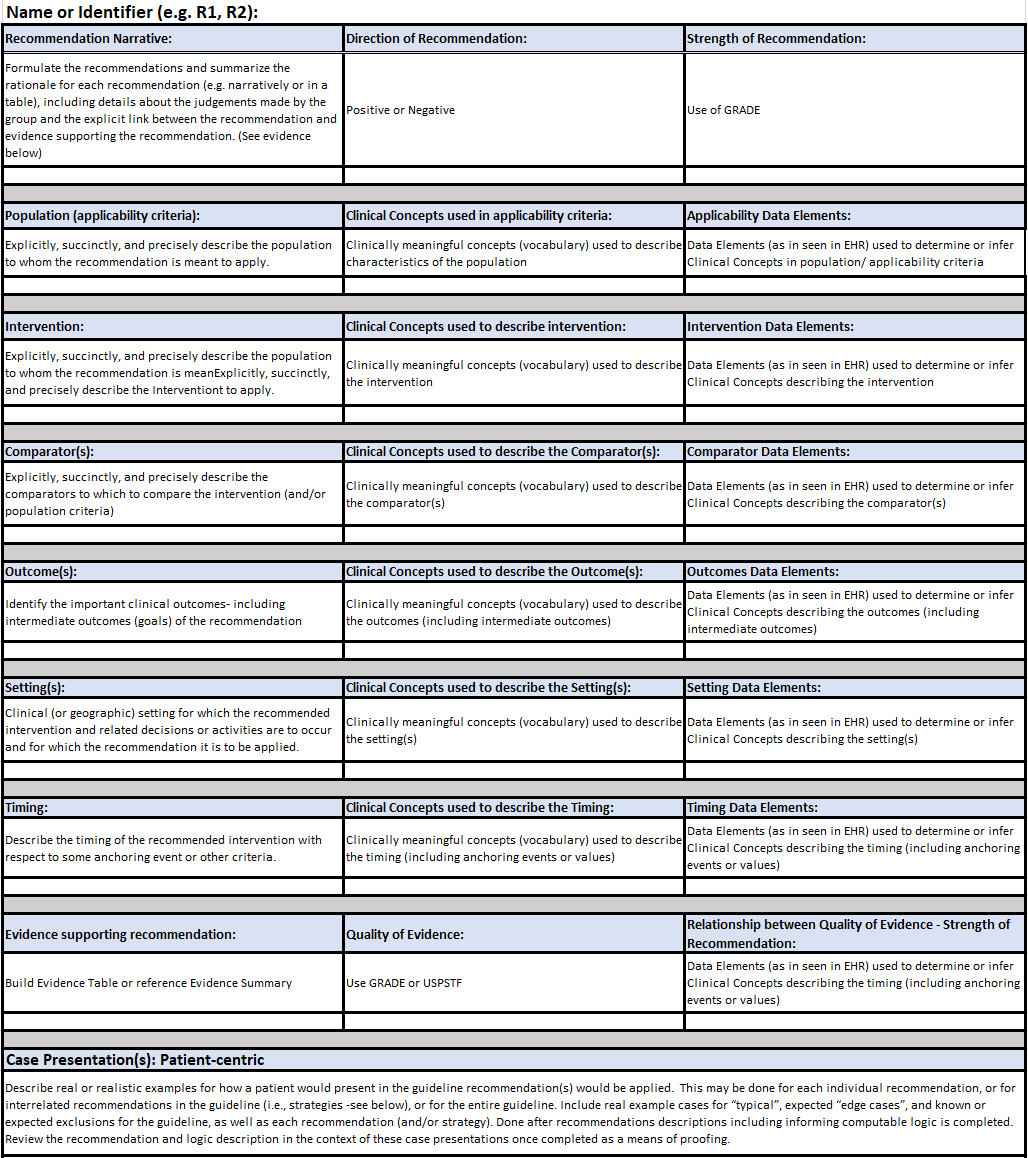

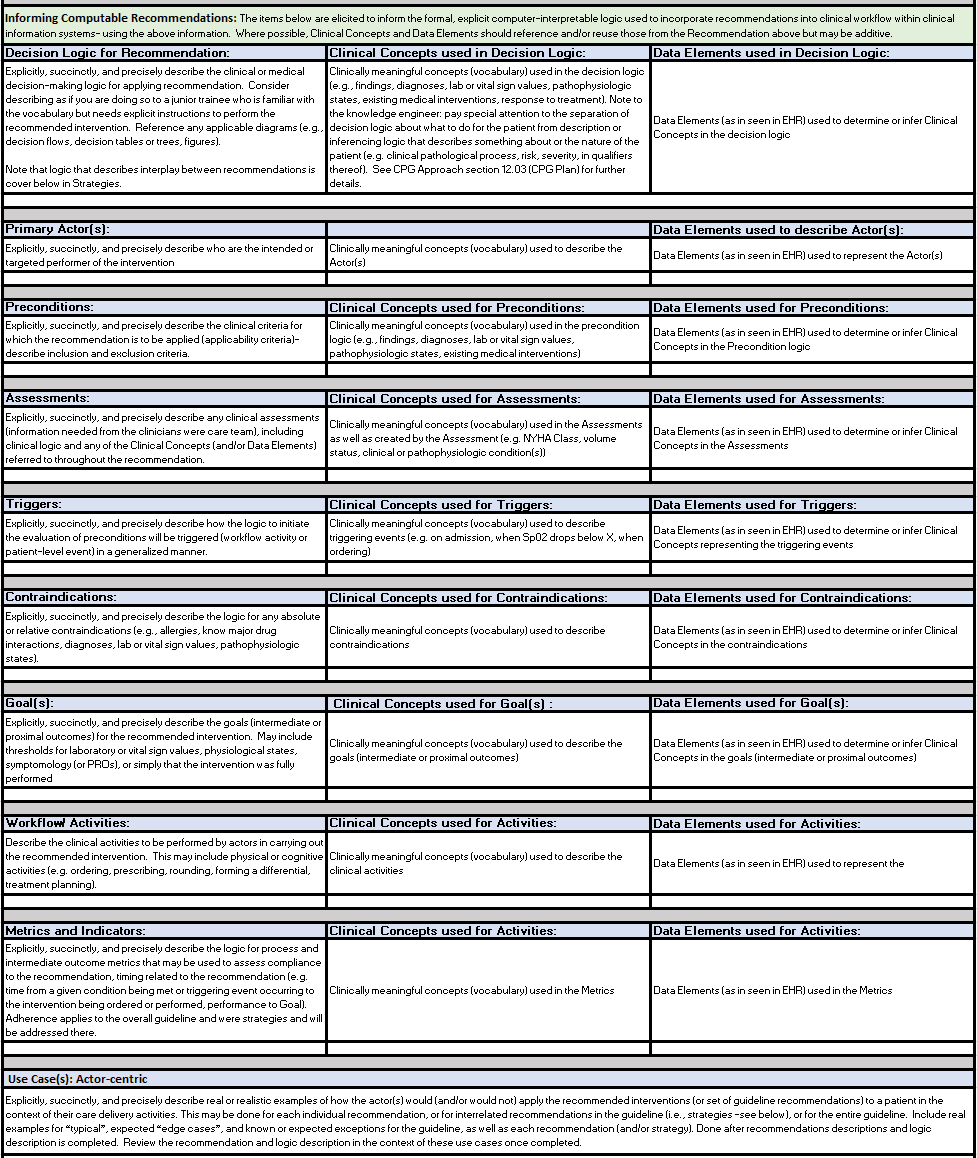

FIG MSC.09. The Structured Recommendation Template includes information such as: PICOTS; GRADES; Evidence Tables; Decision and Orchestration logic- including contraindications, interventions, clinical workflow activities; Metrics/Measures; and Case Presentations and User Stories that are elicited from the Content Team (Clinician SMEs and EMB Experts) together with the identification of Clinical Concepts and the expected representative clinical Data Elements It is situated across the Level 1 to Level 2 spectrum and spans the Data, Logic, and Forms Tiers. As such, this is a critical, definitional work product of the Agile CPG Team.

This template was based on tables and guidance provided by guideline development best practice resources (e.g. McMaster, NIH, CDC) with enhancements for knowledge elicitation and translation and is shared in the Tools and Checklist section of this implementation guide and the final work product can be found in the Examples section.

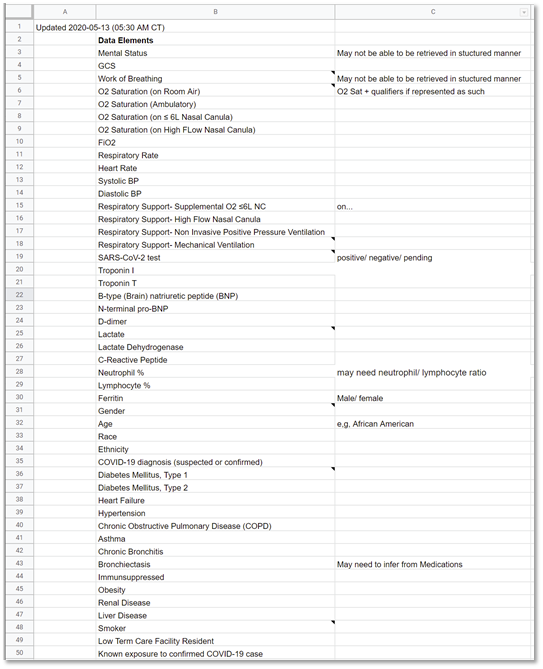

One of the earliest activities that the clinical knowledge engineer was to identify as many clinical concepts and potential data elements that may be used to express and/or infer those concepts for the scope of the entire guideline. The evidence (literature) was reviewed together with early summaries thereof, along with the initial draft of the severity classification and disposition guidance decisions. The concepts and respective data elements identified were fairly exhaustive and ultimately included a number of concepts not required for the logic of the COVID ED CPG “proper”. However, it was expected that while the vast majority of these concepts may represent elements of the evidence that might not ultimately inform the CPG logic for scoring and recommendations, they had potential to be of significant value in outcomes, health services, and clinical research and were of the nature to be collected as part of the feedback mechanism enabled by the “eCaseReport” (i.e. a clinical registry scoped to the CPG content).

The clinically meaningful concepts and respective data elements were then transferred to the Clinical Concepts and Data Elements Table (spreadsheet) for further definition, clarification, codification in standard terminologies (and value sets), and mapping to/from interface terminologies as expressed in real-world EHRs. Additional Clinical Concepts and respective Data Elements were elicited, clarified, and/or verified through the activity of eliciting structured information for the Recommendations, Strategies, and Pathway as described next.

The information sought, elicited, described or stated explicitly, clarified, and/or validated in a formal, structured approach. Elements included:

Figure MSC.10. Part 1 The Structured Recommendation Template used for capture of explicit/structured information for recommendations, decision logic, and workflows

Figure MSC.11. Part 2 The Structured Recommendation Template for capture of explicit/structured information for recommendations, decision logic, and workflows

The information for collections of related Recommendations, called Strategies, as well as for the overall guideline scoped to all Recommendations and all Strategies, called the Pathway were similarly elicited, described or stated explicitly, clarified, and/or validated in a formal, structured approach similar to the individual Recommendations as described above.

Strategies include:

Pathway:

All structured information captured in the CPG recommendation template was analyzed by the clinical knowledge engineer and terminologist to identify key clinical concepts and their respective data elements (used to represent/ express directly or for inferring/ informing such concepts), with further elicitation and verification from the clinical domain experts. The concepts and data elements were then transferred to another template (spreadsheet) used exclusively for formalizing and expressing computable clinical concepts (clinically semantic data) in downstream work products (e.g. decision logic in CQL).

The information content requirements for the individual CPG Profiles further drove the requirements for detailed and explicit information to be elicited from the clinical domain experts and captured in the structured template.

Much of the information needed to define the explicit content of the various CPG Domain and Activity Profiles for recommendations and respective activities, strategies, pathway, case features, metrics, and more is captured in this document.

This information was elicited, analyzed, and further refined to be made explicit over the course of numerous working sessions, interviews, and asynchronous communications with the clinical domain experts (content team). Further definition of the case features (including inferred case features) is described next in the section titled: “Identification and Description of initial Clinical Concepts and Data Elements used in the Guideline”.

Note: while more explicit narrative descriptions of decision and orchestration logic is captured in this document, much of the formal decision and orchestration logic to be expressed in various computable language libraries (e.g. CQL) used in or by the CPG Profiles is more formally and explicitly defined, refined, and verified in additional activities described below (e.g. Decision Flow Diagram, Decision Tables and Decision Requirements Diagrams [DMN], Pathway and Strategy Logic/ Orchestration Models [CMMN]). Some of these activities cross or combine what might be considered Level 2 and Level 3 representations through the use of fit-for-purpose authoring tools that express computer-interpretable logic using visual analogs. Such tooling is invaluable for establishing a shared understanding and more so “reasoning intent” between domain experts and computable logic expressions.

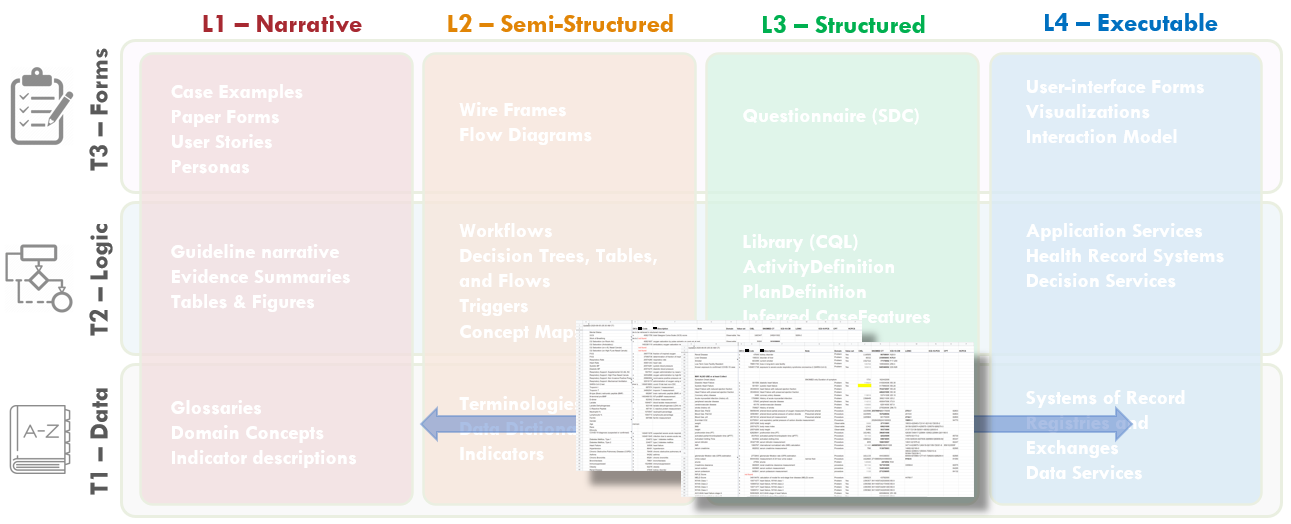

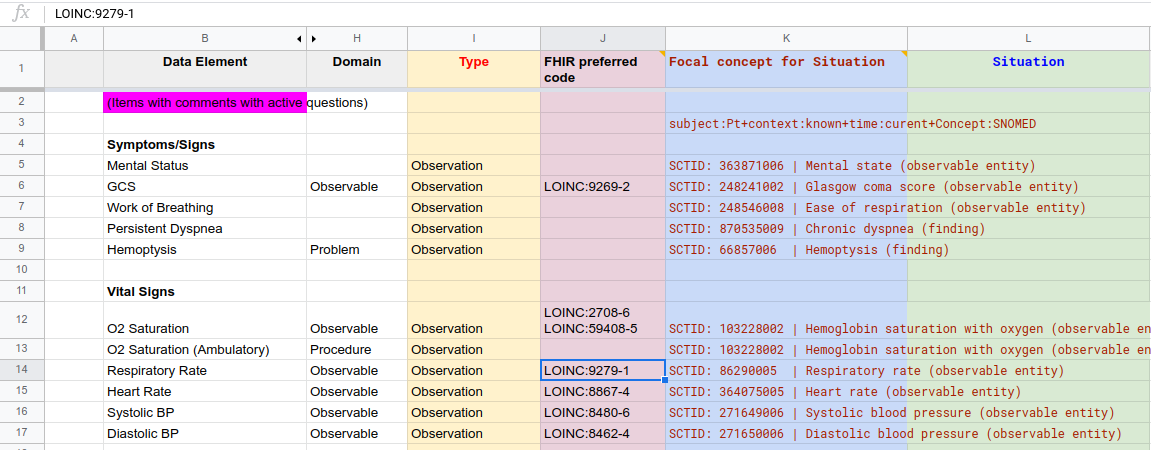

FIG MSC.12. Clinical Concepts and Data Elements with their descriptions were abstracted from the draft of the guidance above by the SME Knowledge Engineer with participation and review by the Content Team and Terminology resources. This artifact clearly lies in the Level 1 space and the Data Tier.

The clinical knowledge engineer and terminologist identified all potential clinical concepts and data elements that may be used to represent, resolve, and/or infer those clinical concepts from the structured template above as well as a thorough review of successive drafts of the Clinical Practice Guideline.

The clinical concepts were reviewed with the clinical domain experts on the content Team (serving as the guideline development group). After these were clarified and/or verified, they were shared with the technical knowledge engineers as well as representatives from the terminology vendors that service healthcare delivery systems in the context of their EHR’s and other clinical information systems for review, further iteration (e.g., clarifications on definitions) to ultimately provide coded concept definitions specific to context-of-use as well as mappings to proprietary (vendor) codes and value-sets used in system interface terminologies.

Figure MSC.13: Identification of Concepts and Data Elements

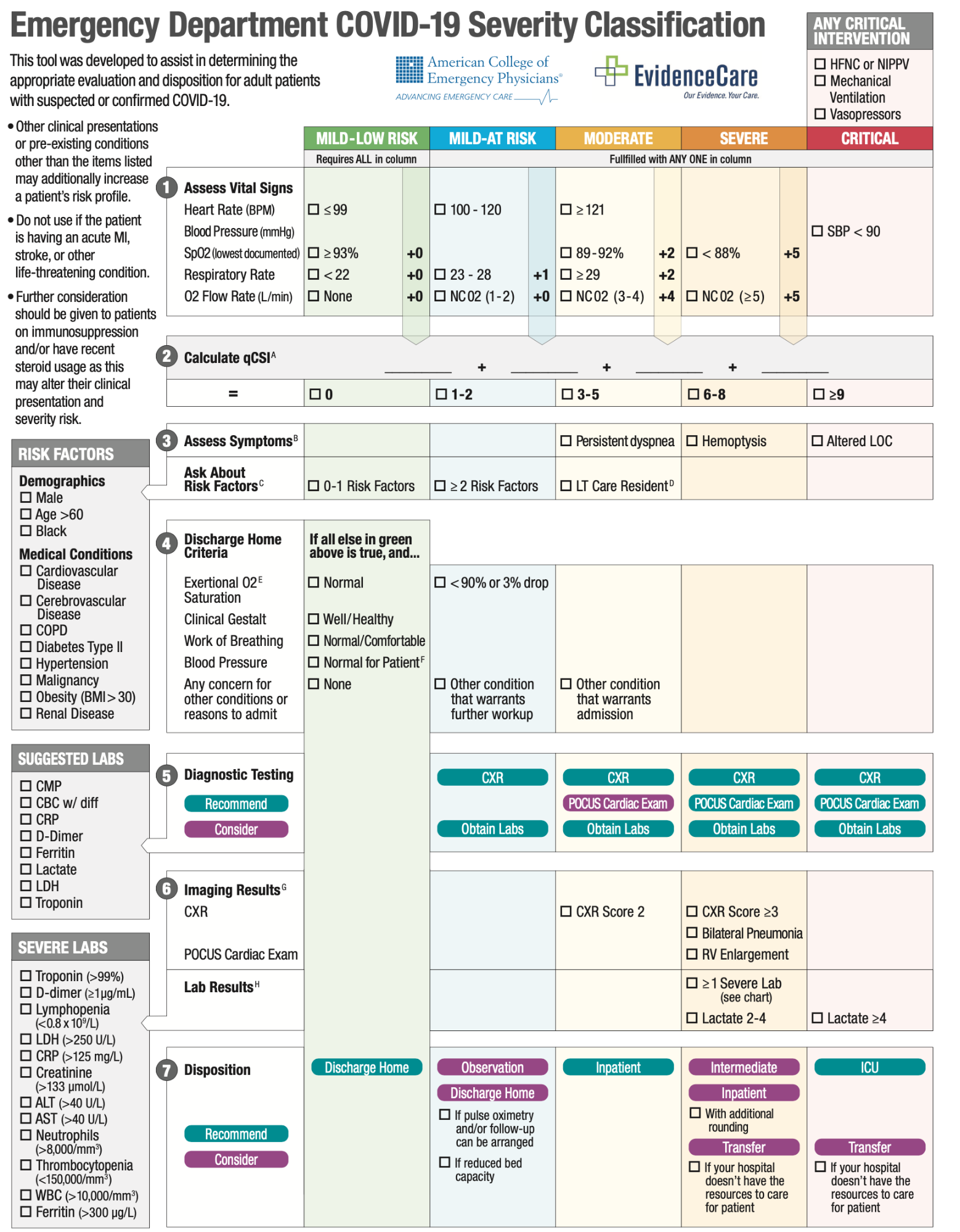

In part to accelerate the translation process and minimize rework and errors of mistranslation, a more explicit means of concept definition and mapping was undertaken by a cross-functional team using both a formal Clinical Ontology to explicitly model and describe concepts (in Protege) as well as Decision Requirements Diagrams and Decision Tables from OMG’s Decision Modeling Notation (using Trisotech). Both are described further below.

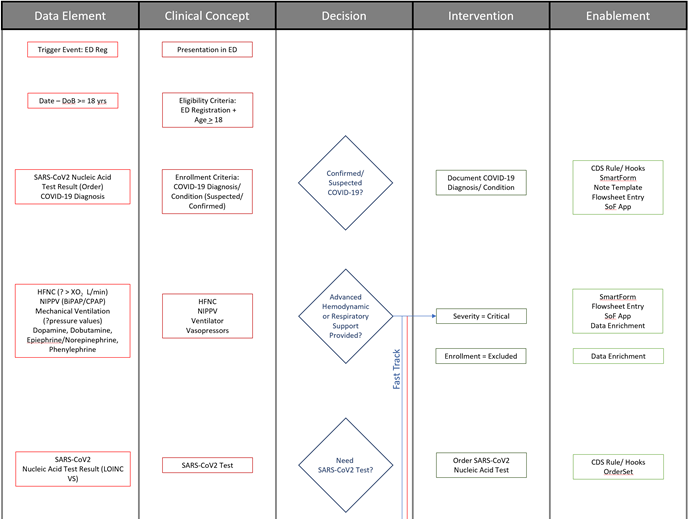

FIG MSC.14. The Decision Flow Diagram contains five lanes- the first two lanes being Data Elements and Clinical Concepts, the middle lane being Decision points and flow, the fourth lane being Clinical Interventions (Activities), and the fifth lane being potential decision support interventions or Enablements to manifest a specific clinical intervention. As such, this semi-structured flow diagram is clearly situated in the Level 2 space and across the Data, Logic, and Forms Tiers. Furthermore, it serves as a tool to span the gap between the narrative and structured representations and facilitates conversations and a shared understanding between the Content SMEs, SME Knowledge Engineers, Terminologists, and Technical Knowledge Engineers. As such, it is partially built from and used in combination with the Structured Recommendation Template.

To make the overall flow of logic for recommendations including decisions and temporal orchestration implied, but not explicit in the illustration developed by the content team (Guideline Development Group), the clinical knowledge engineers developed an explicit decision and activity flow diagram for this clinical practice guideline.

The Template for such a flow diagram has been used in numerous prior guideline/ pathway translation initiatives. This template is a vertical flow diagram with five vertical columns showing the logical and temporal flow of information and activities expressed by descending vertical flow.

The columns further express information flow and dependencies, except between the higher-order separation of concerns of Case, Plan, and Workflow. The foremost left column shows the Data Elements that are required or used to resolve or infer the Clinical Concepts in the second column from the left, collectively representing the Case via CaseFeatures (and as more explicitly defined in prior steps described above and ultimately in the Clinical Ontology). Then, the Clinical Concepts in the second column are used by/ as inputs for the Decisions (that are described in detail in the explicit narrative for Decision Logic in the Structured Template) in the middle column. These Decisions then drive the Interventions or Activities (of a corresponding Recommendation) in the adjacent (fourth) column, and/or downstream decisions, and/or downstream inferred Clinical Concepts. The foremost right (fifth) column describes the CPG Enablements that may be used to manifest these Interventions/ Activities in the clinical Workflow.

Fig. MSC.15. The initial portion of the Decision Flow Diagram for the COVID-19 ED Severity Classification and Disposition Recommendation CPG.

Fig. MSC.16. Together, the Structured Recommendation Template, the Decision Flow Diagram, and the Data Definitions for the COVID-19 ED Severity Classification and Disposition Recommendation guidance form the basis of shared understanding between Content SMEs (Clinicians and EMB scientists) and the Knowledge Engineering Team (SME and Technical KE’s, Terminologists). These artifacts cross-reference and reinforce one another as they span the Levels 1, 2, and 3 space and cross the Data, Logic, and Forms Tiers.

The above work products of the Agile CPG Team (largely the Clinical Knowledge Engineer with significant contributions from the clinical domain expert, the Terminologist, and the Technical Knowledge Engineer) are reviewed and cross-referenced to identify and resolve any inconsistencies, ambiguities, and/or missing elements. This step requires an integrated, cross-functional design review consisting of all the team members denoted so far. This review may identify additional clarifications needed from the content team, may identify additional clinical concepts, data elements, and or logic that needs defined, may identify ambiguities or errors in the narrative guideline artifact(s), and/or may denote areas of particular focus for further review in downstream translation activities (e.g., Decision Modeling, Pathway/ Strategy Logic Modeling).

For this particular CPG, of note, it was through this process that the need to explicitly describe, call-out, and model the continuously monitored “Fast Track for Respiratory and/or Hemodynamic Support” was identified. It had previously been described as an exclusion or exemption from the pathway, when in fact it was a critical, integral part. All guideline artifacts and work products were updated to reflect this.

Other items discussed were:

FIG MSC.17. The formalization of the terminology mapping- from Interface Terminology codes and value sets to Standard Terminology codes and value sets) actually spans Levels 2, 3, and 4 (as they are used in real-world implementations) and is largely focused on the Data Tier- though some description logic may be addressed here.

Following the review and cross-referencing step of work products and artifacts produced in the clinical domain knowledge engineering phase , the next phase of the work involves normalizing the data elements and mapping these to standard terminologies to insure interoperability of the computable CPG. The following outline provides a detailed list of steps takes to complete this work.

Figure MSC.18. Formalization of Term mappings of Terminologies for Data Elements and Concepts

FIG MSC.19. The Content Team has continued to iterate on the COVID-19 ED Severity Classification and Disposition Recommendation guidance. As the severity classification, including decision logic and workflow implications, and disposition recommendations continue to mature and evolve, these illustrations further drift into the Level 2 space and cross the Forms, Logic, and Data Tiers.

The Content Team (Guideline Development Group)

The Content Team has continued to review the evidence for patient characteristics and risk factors contributing to COVID-19 Severity.

The Content Team further takes into consideration feedback and explicit definitions derived from their interactions with the Knowledge Engineering Team as well as representative front-line clinician users. In addition, further feedback and clarification is derived from interactions with medical illustrators who are participating in developing the visual representation of the severity classification, workflow, and disposition recommendations.

Throughout the course of the CPG development, multiple iterations of the visual depiction (illustrations shown), were undertaken by the Content Team.

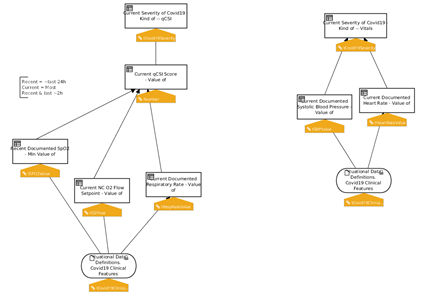

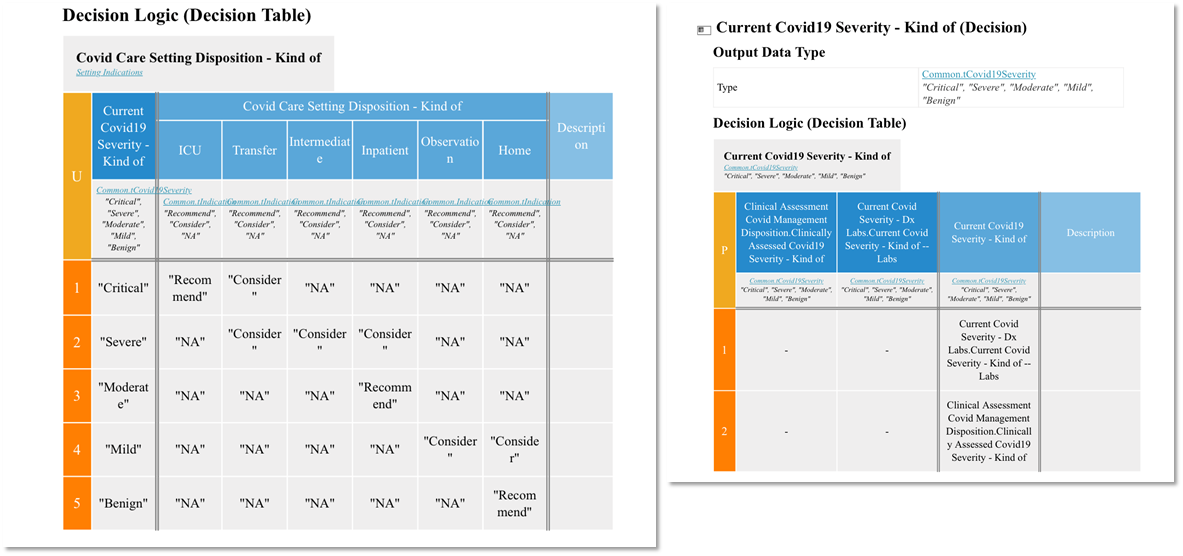

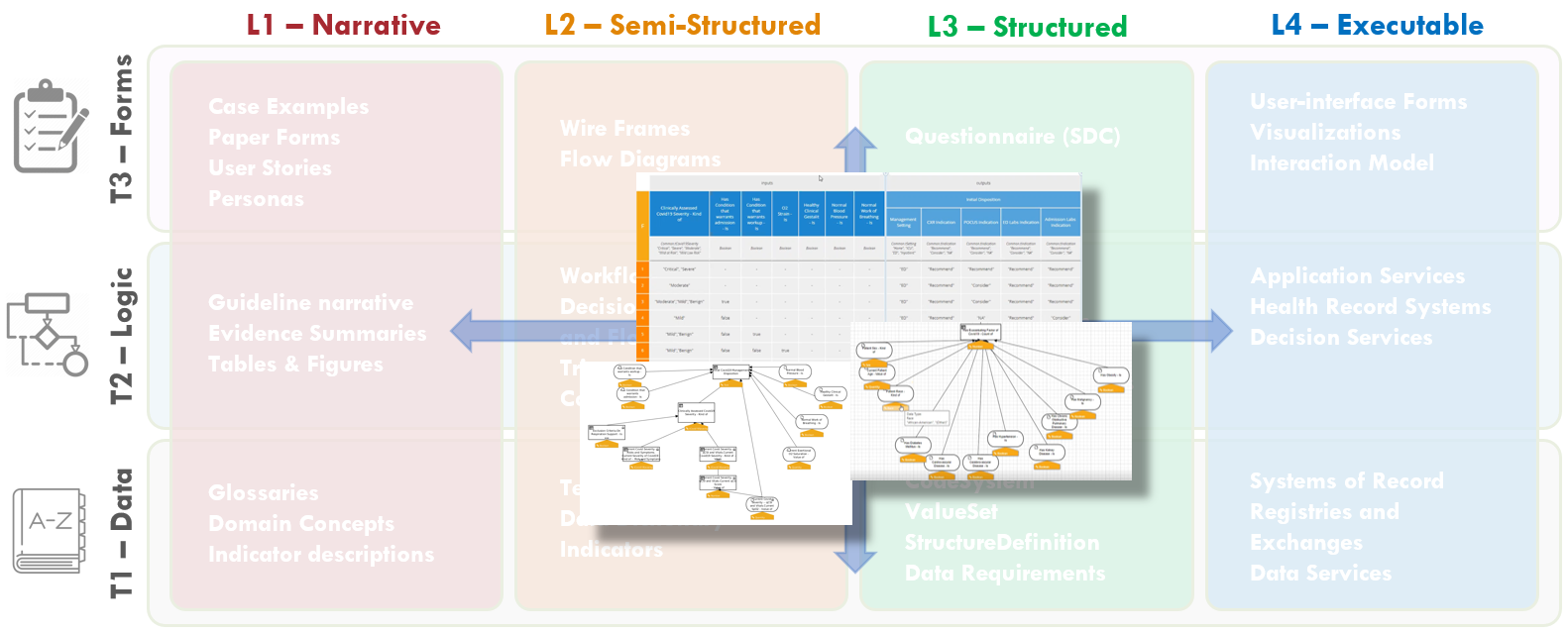

FIG MSC.20. Computable representations of decision logic (Decision Graphs and Tables in DMN) were developed by the technical Knowledge Engineers based on the various Level 2 artifacts developed to date (Structured Recommendation Template, the Decision Flow Diagram, and the Data Definitions) as well as direct interactions with the Content SMEs. These decision graphs and tables span Levels 2 and 3 representations as well as the Logic and Data Tiers. They explicitly represent the clinical concepts and logic in computer-interpretable forms, but are reviewable with Content SMEs.

Based on the various Level 2 artifacts- Structured Recommendation Template, the Decision Flow Diagram, and the Data Definitions- together with direct interactions with the contents SMEs, the technical knowledge engineer developed computable representations of assessment and decision logic including Decision Graphs and Tables (in DMN). These Graphs and Tables explicitly represent the clinical concepts and logic in computer-interpretable forms, but were reviewed with Content SMEs.

The first step in the formalization of the Assessment logic is the identification of the dependencies between the clinical concepts, in particular with respect to those concepts that will be resolved by means of computable expressions.

The resolution of a concept is the process by which a concept is assigned a specific value in the context of a given patient case. Resolution can be implemented by querying the EHR, having some clinician document the data, or by means of computation.

A dependency between two concepts A and B implies that A can be resolved to a higher degree of correctness and accuracy if B itself has been resolved. In the case of expression-based resolutions, B is usually an input to the function that computes A.

The Decision Modelling Notation standard (DMN) provides Decision Diagrams that allow to assert, visualize and consequently review the mutual dependencies between concepts. An example is provided in Fig. MSC.21

Figure MSC.21. Formal model of inferences and decisions: decision diagrams

Input concepts, depicted using oval shapes, represent concepts that are Retrieved from the EHR, or acquired by means of Documentation. Decision Elements, depicted by boxes, model the inference processes that a human would use to infer derivative concepts.The diagrams provide a clear, holistic view that can be validated by the SMEs, in particular to verify that all and only the desired dependencies are captured.

Once the concepts have been properly positioned, the next step consists in creating an initial draft of the expression logic that defines how each concept should be resolved.

Decision tables, decision trees and/or simple expressions can be combined together in forms that facilitate the interaction between the (Clinical) Knowledge Engineers and the Subject Matter Experts.

In this phase, the goal is to determine gaps, redundancies, conflicts, ambiguities and other inconsistencies in the logic, and solicit SME feedback accordingly.

FIG MSC.22. Formal model of inferences and decisions: Decision Tables

Figure MSC.23. The Enriched Term Mappings Sheet for the COVID-19 ED Severity Classification and Disposition Recommendation guidance further formalizes the description and contextualization logic required for the “Clinical Ontology” used within the various logic expressions and representations (e.g. Decision Tables and Graphs (DMN), Orchestration Logic (CMMN)). As such, this artifact is squarely situated in Level 3 and the Data Tier.

In this step, the output of #7 Formalize Term Mapping (table of Data elements mapped to terms & value sets from standard terminologies) is enriched to form the substrate for generating Situation terms based on Situation patterns . This involves adding 4 new columns to the Term Mapping Table:

Figure MSC.24. COVID- ED Severity Classification - Term Enrichment Mappings Sheet

FIG MSC.25. Open items, questions, and clarifications from various interactions collectively and individually with the members of the Content Team, Terminologists, and Technical Knowledge Engineers were documented by the SME Knowledge Engineers. This documentation covered aspects of and had implications for Levels 1-3 and covered Data, Logic and Forms Tiers.

The SME Knowledge Engineers took copious notes on open items, questions, and clarifications from various interactions collectively and individually with the members of the Content Team, Terminologists, and Technical Knowledge Engineers. These questions and clarifications were documented and sent to the Content Team lead for resolution with the broader Content Team. These questions included clarifications on cutoffs or thresholds, ambiguities in logic, and clarifications of data definitions, scoring logic, and workflow implications.

These included:

FIG MSC.26. The Content Team has continued to iterate on the COVID-19 ED Severity Classification and Disposition Recommendation guidance. As the severity classification, including decision logic and workflow implications, and disposition recommendations continue to mature and evolve, these illustrations further drift into the Level 2 space and cross the Forms, Logic, and Data Tiers.

The Content Team (Guideline Development Group)

The Content Team has continued to review the evidence for patient characteristics and risk factors contributing to COVID-19 Severity.

The Content Team further takes into consideration feedback and explicit definitions derived from their interactions with the Knowledge Engineering Team as well as representative front-line clinician users. In addition, further feedback and clarification is derived from interactions with medical illustrators who are participating in developing the visual representation of the severity classification, workflow, and disposition recommendations.

Throughout the course of the CPG development, multiple iterations of the visual depiction (illustrations shown), were undertaken by the Content Team.

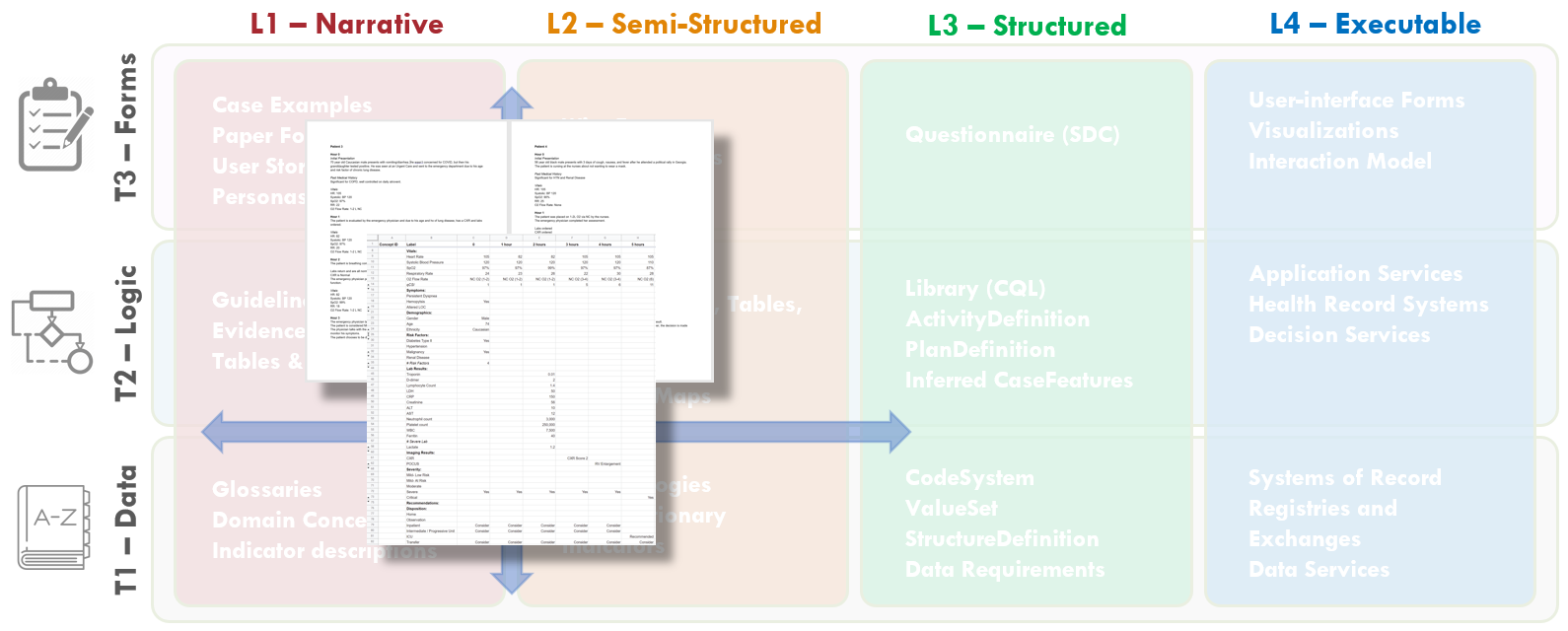

FIG MSC.27. Case Presentations and Test Cases were codeveloped by Content SMEs and SME Knowledge Engineers. The content of these case presentations and test cases covered Levels 1 and 2 and addressed all Tiers, but further help span the gap between Levels 1 and 3.

To test the logic under “real world” scenarios of patients, the variation of clinical manifestations that they can present with, and the dynamic nature of which their physiology can change quickly, a series of test cases were created by the Clinical SME group to allow the KE group to test the logic built into the use case. Each use case was designed to test particular scenarios of a patient switching from a Severity Classification to another as new information is received about the patient, such as a new lab result, changing vital signs, imaging results, etc.

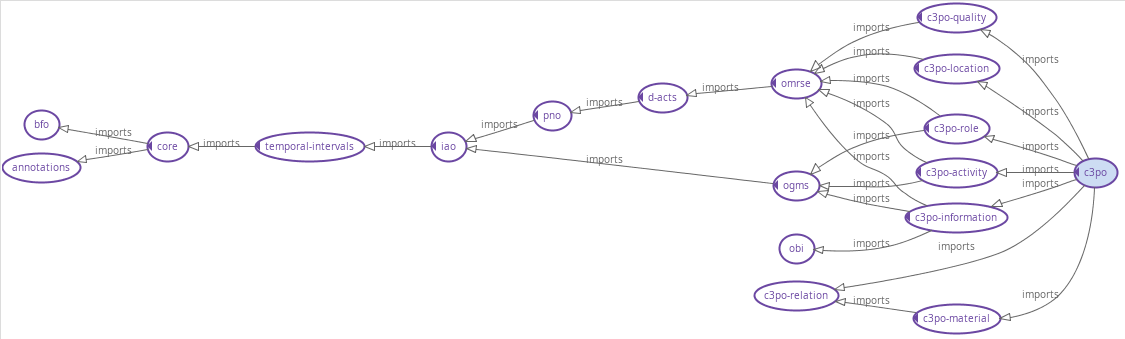

FIG MSC.28. The Clinical Ontology is a shared conceptualization of the overall clinical care process for the COVID-19 ED Severity Classification and Disposition Recommendation CPG where all concepts are made explicit such that they can be not only discussed and described among domain SMEs, but modeled and used computationally. As such, the Clinical Ontology spans the gap between Levels 2, 3, and 4, but may be considered a Level 3 artifact that largely addresses the Data Tier, but address description/ assessment logic in the Logic Tier as well.

The Common Clinical Care Process Ontology provides a shareable conceptualization of the Clinical Care process such that it can be discussed, described, analyzed, modelled, governed, and supported (e.g. with Information and Knowledge Management tools) effectively- in part, through use of consistent, common, and sufficiently detailed vocabulary. Of note, the formal approach taken here leads in the direction of computability, allowing to consume the semantically well-founded artifacts at a larger scale.

At the highest level, the C3PO will describe features and patterns of a generalized abstraction of different kinds of Clinical Guidelines and Care Processes. These in turn will allow the description of clinical workflow patterns, clinical concepts, terms as well as term enrichments.

C3PO is an application ontology built on a framework of Basic Formal Ontology (BFO) and Ontology for General Medical Science (OGMS) along with modules from OMRSE & OBI . These provide the upper and domain level frameworks on which the following axis have been developed:

These axis reuse terms from existing ontologies and are enhanced with terms required for computable clinical guidelines.

Principles of C3PO development

C3PO import graph

FIG MSC.29. A hierarchical view of the C3PO modules as well as the framework ontologies. The generated ontology modules for the clinical guidelines will be added as sub-domain ontology modules.

Class hierarchy

FIG MSC.30 View of the C3PO class hierarchy. The generated ontology terms for the clinical guidelines (e.g. for COVID-19 ED Severity Classification and Disposition Recommendation CPG) will use this hierarchy.

The formalization of the CPG consists in the creation of a series of L3 artifacts which are expressed using standard and formal languages. A formal language is a language that is specified by means of a formal grammar, which makes it machine-readable, and is defined to have formal semantics, which makes it machine-executable.

The process consists in a translation from a (structured) human readable language into a machine-consumable language and is usually a specific responsibility of a Knowledge Engineer. To ensure a faithful translation, the choice of language and tooling is critical.

In the broad landscape of standards for knowledge representation and reasoning, each component of the CPG can usually be represented using different languages, which can be specific to a formalism (rules, ontologies, processes, etc.) and/or a business domain (healthcare, finance, etc.). The notion of using different languages based on topic and audience is normal in L1/L2 artifacts, where the choice usually involves natural languages (e.g. English, Chinese, and Italian) and multi-media (e.g. text, audio, diagrams).

Analogously, L3 languages are chosen based on their fitness to express certain parts of the CPG. When multiple alternatives exist, mappings and translations can be used to derive alternative representations from an initial source. In this sense, the choice of the initial language itself becomes less dogmatic, but rather contingent on the Knowledge Engineer’s expertise, availability of tooling and consumer priorities.

In this sense, the FHIR architecture provides one candidate Knowledge Representation meta-language – the FHIR StructureDefinition – and several Profiles that can be mapped to ontology languages (e.g. OWL), rule languages (e.g. DMN, Arden Syntax), process languages (e.g. BPMN, CMMN).

FIG MSC.31. DMN diagrams/models (tables and graphs) express the assessment/inference logic as executable decision models that can be reviewed with Content SMEs. As such, these explicit, computable diagrams and models with their visual representations span the Level 2 and 3 space and primarily address the Logic Tier with explicit implications for the Forms and Data Tiers.

When DMN is chosen as the primary language for the formalization of the Assessment/Inference logic, the initial DMN Diagrams are turned into formally executable decision models.

Most DMN decision modeling tools are equipped with syntactic checkers, semantic validators, testing and simulation tools that support the Knowledge Engineer throughout the process.The fundamental goal of this step is to further refine the preliminary decision tables / expressions into fully computable ones which can be executed and validated.

In doing so, two complementary aspects should be considered:

Formalization and Optimization of the Datatypes associated to the Concepts

The datatypes define local ‘view’ schemas that hold the values associated to the resolved concepts. The datatypes should be consistent and reusable across concepts, and should be designed to support the information processing.

Languages such as DMN and CQL provide basic datatypes (strings, numbers, dates) that can be composed into more complex ‘structures’ which carry correlated information through the computation. These structures are local, and thus optimized for, the inference logic, and do not necessarily correspond to the (much more complex) structures used to persist and exchange information (e.g. FHIR resources).

Stratification of the Logic The chaining of ‘decision steps’ usually highlights operations that are performed for different purposes:

This meta-categorization is not only useful to maintain explicit connections between the formalization and its clinical intent, but can also help identify patterns to verify and optimize the logic itself.

In the CoVid19 ED example, the qCSI score itself is a mathematical calculation based on the patient’ vitals which participates in a broader classification of the patient’s disease severity. The severity, in itself an estimation of the current state of disease progression, is used to predict the likelihood and degree of the patient’s devolving if left untreated. This assessment ultimately determines the indicated therapeutic interventions.

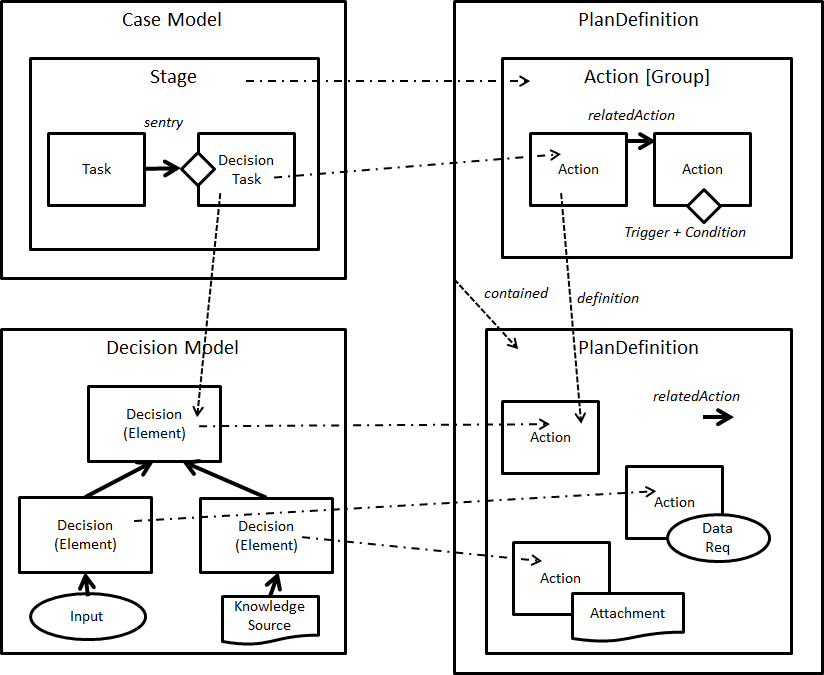

<div>

<img src="image38.png" width="750"/>

</div>

FIG MSC.32. The “Care Process Model” as the Pathway and Strategies’ decision and orchestration logic, together with Tasks (decision and human), Goals, Roles, Interventions, and their respective Control Flow logic are modeled as CMMN (OMG Case Management Modeling Notation). These models are both computer interpretable as well as having explicit visualizations that are reviewable by Content SMEs. As such, these artifacts are situated across Levels 2 and 3 and largely address the Logic Tier, but have explicit implications for the Forms and Data Tiers that are both computable and human reviewable.

The ‘Care Process Model’ component of the CPG focuses on the atomic Tasks that are expected to be performed by actors playing different Roles, to achieve specific Goals, under specific Applicability criteria, at specific points in Time . The concepts maps directly to the Activities, Roles, Goals, Preconditions and Events identified during the Knowledge elicitation phase.

Tasks are primarily differentiated between Decision Tasks, which involve the processing of information, and Human (Action) Tasks , which involve actions that require some form of interaction with the clinical environment.

The former can be further distinguished between Assessment Tasks, which lead to the resolution of new Clinical Concepts by means of derivation/inference, and Strategic Planning tasks, whose outcome is aimed to steer the following Interventions . Assessment tasks are defined by means of the Assessment/Inference Decision models, while Strategic Planning tasks are defined by means of the ‘Disposition’ decisions, and can be supported by means of Strategic Recommendations at case execution time.

Interventions can be further divided into Information Gathering (Evaluation) Tasks, whose goal is to acquire more data to be assessed, and Intervention Tasks (in the narrow sense) which are performed to alter the normal (pato)physiological course of the patient.

The language of choice for the representation of Care Process Models is OMG’s CMMN. CMMN is designed to handle “adaptive” Case Models, i.e. Cases whose course is determined by events whose sequence is not completely predictable at design time, and which require some strategic planning as the case unfolds.

In a Case model, the primary notions are those of ‘Stage’, which can be used to model clinical stages (e.g. ED vs surgical setting) and/or disease stages, (Triggering) ‘Event’, (applicability) ‘Condition’ and Task (Action). In particular, the sequencing of Tasks is driven by Events (e.g. Task B is enabled upon the event of completion of Task A)

Figure MSC.33. Formal models of full orchestration

CMMN is compatible with DMN: (Decision) Tasks in CMMN can be linked to DMN Decisions, and the two languages can share data elements and data types – mostly by CMMN models reusing elements and types defined in DMN.

CMMN also embeds expressions, which are not used to derive new data, but to evaluate the applicability of Tasks and Stages in reaction to certain events. CMMN is a formal language and has execution semantics. CMMN models can be simulated even during the authoring phase, and can be used to illustrate/validate different scenarios that correspond to (un)desirable courses.

Formal verification tools are not as common as for its companion language BPMN, but would be valuable. In particular, Knowledge Engineers should verify that Case Models are viable, i.e. it is impossible for a sequence of events to lead to a case that (at least according to the model’s specification) cannot be closed other than by aborting the case execution itself.

FIG MSC.34. Thorough, cross-functional detailed review of the initial drafts of the computable models described above- Clinical Ontology, Decision Models (DMN), and Care Process Model (CMMN) individually and collectively.

Representatives from the Content Team, SME Knowledge Engineers, and the Technical Knowledge Engineers conducted a detailed multi-session, cross-functional review of the initial drafts of the computable models described above- Clinical Ontology, Decision Models (DMN), and Care Process Model (CMMN) individually and collectively. All details of the models including their clinical intent and computational implications were thoroughly reviewed. Some of the offering environments (e.g., CMMN) further afford simulation to visualize how case examples would traverse the logic expressions. At each point in the model where either definitions and description logic (as expressed in the Clinical Ontology) or assessment/inference logic (as expressed in DMN), the respective models were reviewed. Feedback on adjustments to the logic expressions for process/orchestration (CMMN), decision and assessment/inference (DMN), and description logic (Clinical Ontology) were fed back to the respective knowledge engineers with explicit documentation. And questions and clarifications based on implications from the computable expressions were fed back to the Content Team. All team members were given explicit tasks and any implications that were determined either out of scope or not currently resolvable were also noted.

The final guideline was generated into a PDF document that was then disseminated by ACEP through its network for close to 50,000 members around the world.

Below is an image of the September 2020 version of the guideline.

Figure MSC.35. Emergency Department COVID-19 Severity Classification (9/2020)

The dynamic URL for the guideline can be found here: COVID-19 Severity Classification Tool

In this stage, the different models are combined together into a Composite model.

Validating the consistency across interaction points should be the main focus of a Knowledge Engineer.For every interaction that is coordinated by the Case model – Events, Tasks, and the information consumed/produced at each point – concepts and related data types should exist to formalize the clinical meaning of the information being transferred.

Assuming that the expressions in the decision models are correct, the timeliness of their evaluation at the point in time specified by the case model should be evaluated.

FIG MSC.36. The various CPG artifacts (e.g. Pathway, Strategies, Recommendations, CaseFeatures, Metrics) are sharable, faithful, computable expressions of the clinical practice guideline for ACEP’s COVID-19 ED Severity Classification and Disposition Recommendation guidance. As such, these artifacts are squarely situated in Level 3 and across all three Tiers.When the different components of the CPG are not authored using FHIR languages in the first place, the translation of the models into FHIR is not determined by the choice of source language, but rather by the nature of the knowledge content.

The same content can be used to obtain iso-semantic, or at least iso-pragmatic representations (i.e. models that carry the same information or at least exhibit equivalent behavior when executed)

| Knowledge Asset | Source | Target |

|---|---|---|

| Concepts with mappings | OWL | SKOS FHIR ConceptMap |

| Primitive Concepts + Datatypes | FHIR Resources / Datatypes | CQL Retrieve FHIR DataRequirement (FHIR Profiles) |

| Enriched Concepts Datatypes (“Situational Data Model”) |

DMN ItemDefinition | CQL ModelInfo CQL ‘Struct’ (FHIR Logical Model) |

| Enriched Concepts Definition | DMN / FEEL | CQL Library |

| Assessment / Inference Model | DMN | FHIR PlanDefinition [Cognitive Process] |

| Case (Process) Model | CMMN | FHIR PlanDefinition [Care Process Model] |

| Case Features | DMN | FHIR Composition [eCase Report] |

| Applicability Criteria | DMN / FEEL | CQL Library |

The core transformations are the mapping of the ‘plan/process’ artifacts, and the expression logic. The former can be framed as follows:

FIG MSC.37 Core artifact transformations

The mapping of the expression logic requires a finer grained discussion. Both FEEL and CQL are functional, stateless expression languages. A translation between the two languages is possible with a few caveats:

In general, CQL is more expressive: mapping from BPM+ into CQL is more likely to be successful than the inverse. Whether FEEL is sufficient , then, remains an open question in general. However, the added expressivity of CQL is mostly used in two places: (i) the Retrieve filters , which are isolated into the ontology-mediated data binding layer anyway, which is executed before the decision/case models, and (ii) complex functions which should be encapsulated anyway (in fact, certain complex functions are better expressed using quantitative languages such as PMML anyway).

The set of core models can be augmented by means of additional derivations. This second category is different because the derived models are neither iso-semantic nor iso-pragmatic. Their generation involves the information in the source model, as well as some additional methodology / technique.

| Knowledge Asset | Source | Target | Derivation Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Questionnaires | DMN | FHIR Questionnaire | DMN decision elements can capture ‘questions’. |

| Recommendations | DMN + CMMN | FHIR PlanDefinition [Strategy ECA Rule] |

“Disposition” inferences can be, formalized as deontic (soft) constraints X → Y indicated can be rewritten as IF X and not Y THEN recommend Y Using the decision in the context of a case model allows to further incorporate triggers and applicability into the rule |

| Quality Measures | DMN +CMMN | QualityMeasure | Likewise, the interpretation of dispositions as constraints allows to derive measures from the count of violations/satisfactions Using the decision in the context of a case model allows to add time boundaries, using (evidence of) the execution of the intervention tasks that are informed by the disposition as measurable data. |

The CPG assets can be validated independently, or as a whole, or both.

The availability of open source FHIR Servers (e.g. HAPI), Sandboxes (e.g. Logica), CQL and ECA Rule engines (e.g. CQF Ruler) allows to test the extraction of the Case Data, the derivation of the individual Case Features, the execution of the Strategy recommendations, and the evaluation of the Quality Measures.

One should not ignore that DMN and CMMN artifacts are also testable using native engines, provided that they are connected to a FHIR data source.

Following the packaging guidance in the CPG implementation guide, the artifacts can be packaged independently, or using an asset collection, which is a Library with composed-of related artifacts references to all the artifacts. For distribution, this can then be packaged in a CRMIManifestLibrary.