This page is part of the Clinical Guidelines (v2.0.0: STU2) based on FHIR (HL7® FHIR® Standard) R4. This is the current published version. For a full list of available versions, see the Directory of published versions

This section provides an overview of the specific separations of concerns in the CPG implementation guide as well as some details of their respective boundary issues. An overview of each separation is covered here and in more detail in individual sections that include:

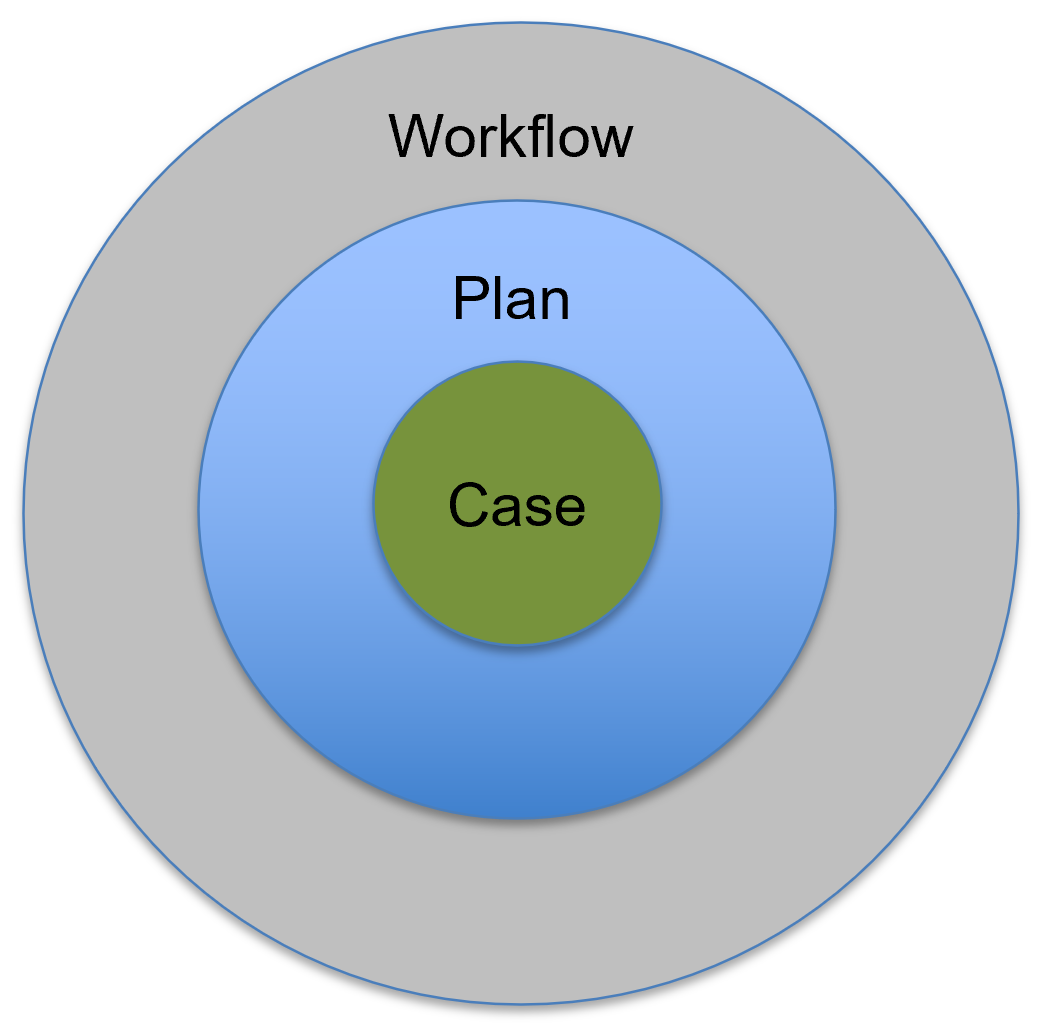

From the domain perspective, a case is conceptualized as the contextually relevant information oriented to clinically meaningful descriptions of an individual patient’s current and historical state of health, disease, and risks. The case includes a comprehensive, detailed description of the current and relevant historical clinicopathological presentation of the patient. Key information to sufficiently summarize the case for the purpose of making appropriate and timely medical decisions in a given situation are often referred to as pertinents (e.g., positive and negative pertinents). Details for the CPGCase are covered in this linked section.

Within the healthcare domain, the providers formulate an approach, or plan, for how they intend to address the health, well-being, and active clinical concerns of the patient, taking into account the patient’s goals and preferences. The plan includes current interventions, takes into account prior and current response to those interventions, and formulates an approach to assess and address all elements of the patient’s state of health and disease. A plan consists of requesting (e.g., ordering, prescribing, scheduling) medications, procedures, diagnostics (e.g., laboratory and imaging, and other tests), and appointments (e.g., referrals and consults).

A plan takes into consideration existing or potential complications, side effects or adverse events for various interventions, and worsening signs and symptoms to watch for, as well as the means to mitigate and/or address potential adverse events. The plan typically addresses each item in a differential diagnosis, and since many patients have multiple conditions, a plan is developed for each problem, including considerations for the severity and urgency needed to be addressed as well as interactions between conditions and/or their existing and planned interventions. A plan often mentions next steps and/or expectations for information (e.g., a pending lab result) and expected/possible/likely decisions to be made.

There exists a fine distinction between and relationship among a plan for best practice care across a population and/or subpopulations; the working care plan for a specific patient by a care team and the care team's cognitive, collaborative, and often poorly coordinated processes of formulating a patient-specific care plan. This latter planning process utilizes, in part, best practice guideline recommendations in the context of patient-specific goals and preferences as well as other conditions and considerations, and awareness of the situational factors of the patient’s current and historical state in the context of their real-world setting.

The patient-specific plan (i.e., Care Plan ) in most healthcare settings can be found across the plan section of current and recent instances of clinician documentation, but must be aggregated across all care team members (e.g., primary team, consulting teams, and documentation from various healthcare professionals), as well as recent, active, and initiated orders or prescriptions or the resulting fulfillment (e.g., medication administration record).

In the CPG, the concept of a plan as a separated concern is further divided into the abstracted, more generalized reasoning and rationale for determining the best course of action for a patient (e.g., recommendations, strategies, pathways) formalized as logic in the Plan and the patient-specific past, current, and likely course of action (e.g., proposals, requests, and fulfillments of those requests) called a Care Plan (described further below) formalized as data elements in the Care Plan. Though there are use cases where have both in context is of considerable value as is described in the CPGCasePlanSummeryView.

Workflow, an often overloaded term in the healthcare domain, refers to the activities in real-world healthcare delivery settings, the human-computer interaction activities which are carried out in the context of clinical information systems (e.g., EHRs), and even some of the interaction within and between those systems. This often refers to human task flow, information flow, and patient flow. Clinical workflow is the description, abstraction, or depiction of clinical work that includes the physical, cognitive, coordination, and computational tasks or activities carried out by individual and teams of clinicians along with other staff and various resources using specialized knowledge, vast amounts and varieties of information, and numerous tools or artifacts collectively to achieve the goal of delivering the safest and highest quality care to individual patients as well as populations of patients or the broader public. Clinical work occurs in a broader system, social, legal, regulatory, and professional context that can greatly influence how this work is carried out.

The CPG-IG explicitly does not address, local workflows due to their significant variation, complexity, and need for consideration for local factors (e.g., specific resources and resource type, policies, customized or localized tooling), as well as to avoid conflating detailed clinical workflow descriptions/definitions with the flow of abstract clinical activities often necessary to describe as part of the care process in guideline recommendations. This topic is addressed in further detail in the subsection on Workflow and the Common Pathway.

As discussed in the section on Knowledge Architecture, it is critical in knowledge-driven approaches to identify accurate, representative, unambiguous, and useful domain knowledge abstractions and for these abstractions themselves to respect domain-oriented separations of concerns. These separations of concerns must be respected within and across the domain conceptualizations, as well as between knowledge formalizations and across the translations or transformations thereof. A related principle is fidelity to domain conceptualizations, where oversimplification leads to unwieldy and value-diminishing complexity to correct for gaps in fidelity, while appropriate complexity to align with the domain yields optimal formalizations.

One of the most critical principles in dealing with these boundary issues is to identify them, recognize that they exist, and then formulate a plan to explicitly address them. There are several best practices for addressing these boundary issues once they have been identified. One such best practice is to use “Layers of Abstraction”. Creating abstraction layers is a means of hiding much of the working details of a component, allowing the separation of concerns to facilitate both interoperability within the knowledge architecture and across implementations thereof. In fact, the “concerns” themselves can be thought of as creating abstraction layers. Often when modeling or architecting a “concern”, one creates fit-for-purpose features for that concern that themselves may be abstracted, which specifically address boundary issues with ‘adjacent’ concerns with which it must interact.