This page is part of the Clinical Guidelines (v2.0.0: STU2) based on FHIR (HL7® FHIR® Standard) R4. This is the current published version in its permanent home (it will always be available at this URL). For a full list of available versions, see the Directory of published versions

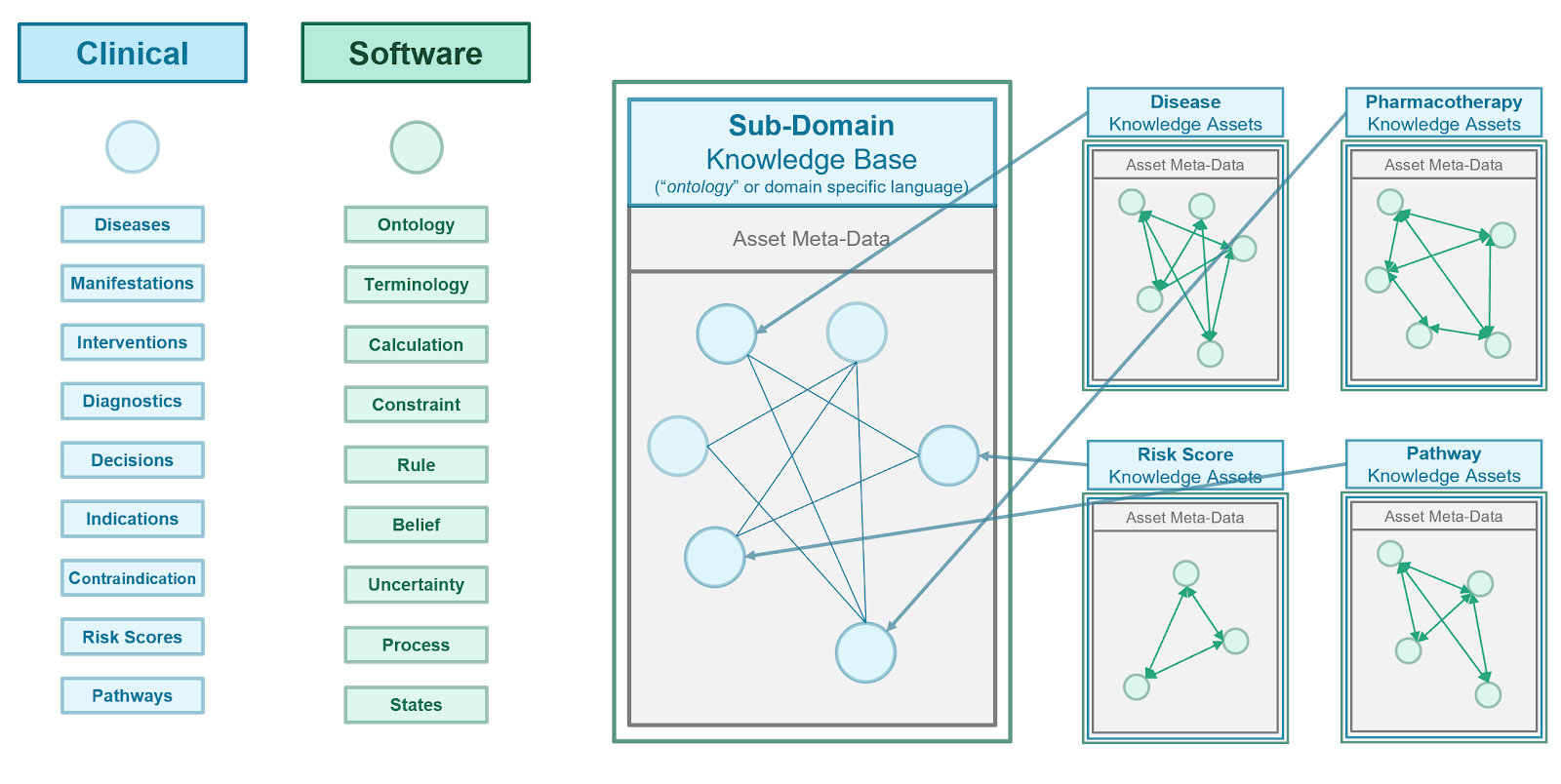

Knowledge architecture is the discipline of information system architecture (Industry, Enterprise, Solution) with a focus on the principles, best practices, means, and mechanisms by which the knowledge assets for the architecture's given domain are managed including: acquiring, representing, stored, and organized. Knowledge architecture includes defining the types and scopes of the various assets, their metadata, as well as their relations. This description of the types and nature of knowledge assets, including the definition of their metamodels including relationships to and in the context of each other (derived, composite, and related assets), may be referred to as the knowledge asset ontology.

Covered in this section:

The CPG Knowledge Architecture (Conceptual Domain Perspective) is described in its own section of this implementation guide.

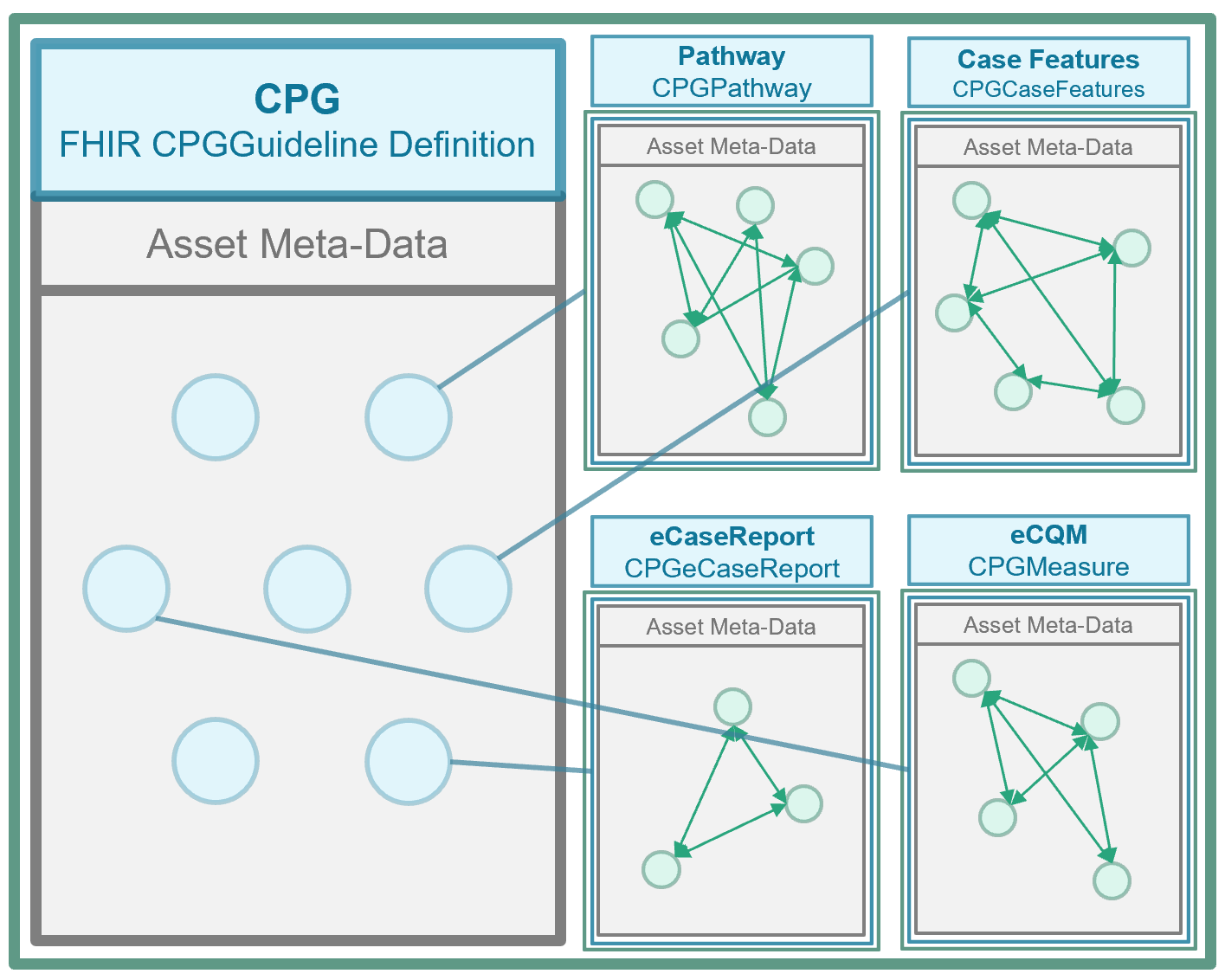

Furthermore, as various asset types and/or their derivatives share many common characteristics, the knowledge architects attempt to use common approaches and information modeling concepts to ensure optimal reuse, adaptation, and subtyping across knowledge asset meta-model definitions. In FHIR, this is done through profiling of definitional resources (e.g. plan definition, activity definition) and is enforced largely through a common approach in tooling to creating these asset type profiles.

Similarly, to ensure reusability, derivation, association, and adaptability as well as reduce rework and confusion by the knowledge engineering team a consistent and accurate definition for knowledge asset metadata is often defined in what may be referred to as the knowledge asset metadata meta-model. In FHIR, this is done in part through architectural oversight of resource and attribute definitions as well as through the use of a common, shared Metadata resource.

2

Needs and best practices include:

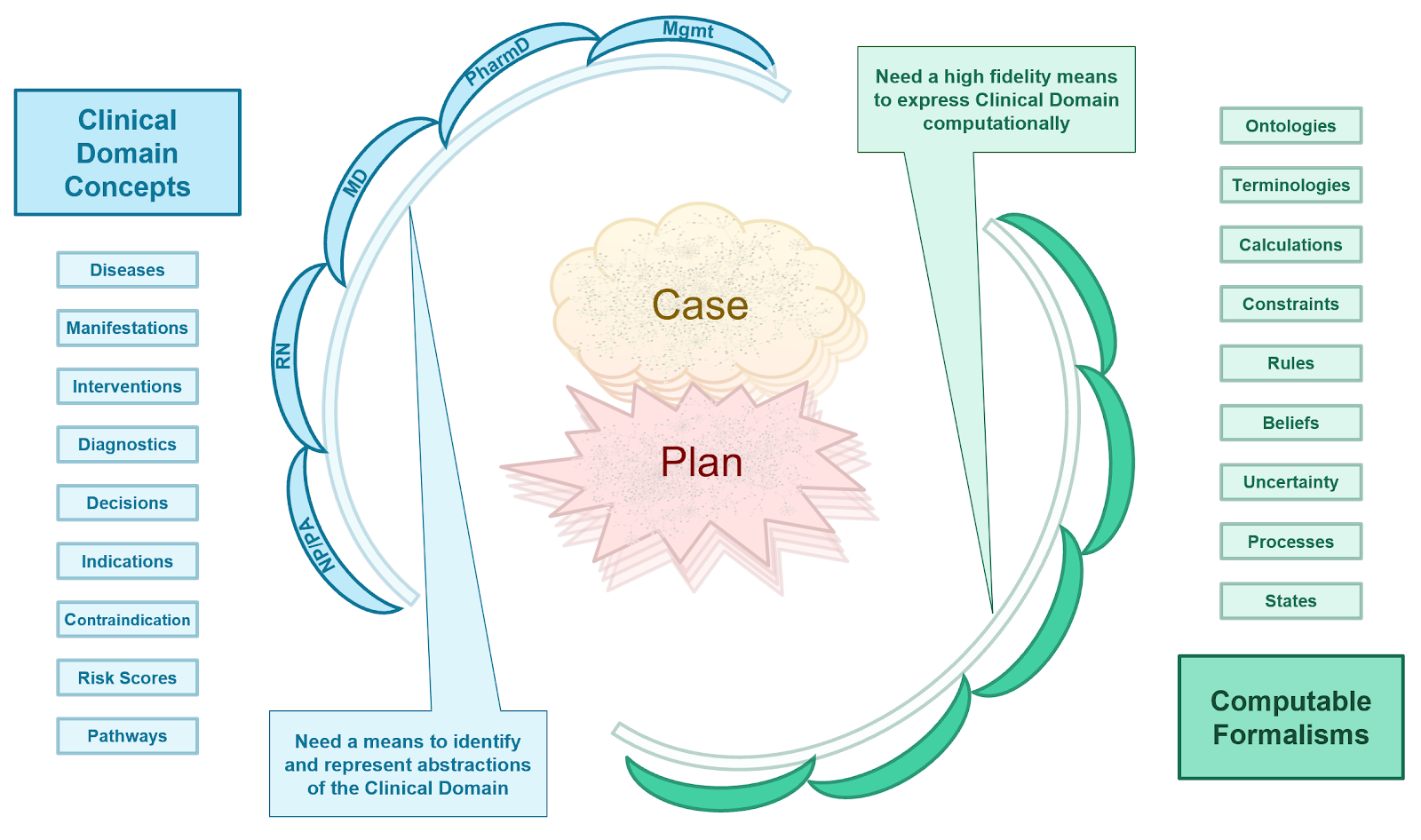

Knowledge Architecture in the healthcare domain poses a particularly challenging domain to architect knowledge for, and for which knowledge architecture approaches, decisions, and implementations can have significant impact on the usability and value of assets as well as for the efficiency and overall effort of the knowledge engineering team(s). Furthermore, the participants in these activities include a broad and deep representation of highly technical and specialized skills and foundational knowledge including clinical medicine and healthcare delivery, computational sciences and software engineering, knowledge and evidence ecosystem participants, and the knowledge engineering discipline.

Key considerations and principles:

Knowledge Architecture Principles as Applied to the CPG

Developing the CPG Knowledge Architecture

Here we describe the overall knowledge architecture approach to developing the CPG knowledge architecture, which then results in the Conceptual Perspective on the CPG Knowledge Architecture as well as the concretized Knowledge Architecture in FHIR for the CPG-IG described subsequently.

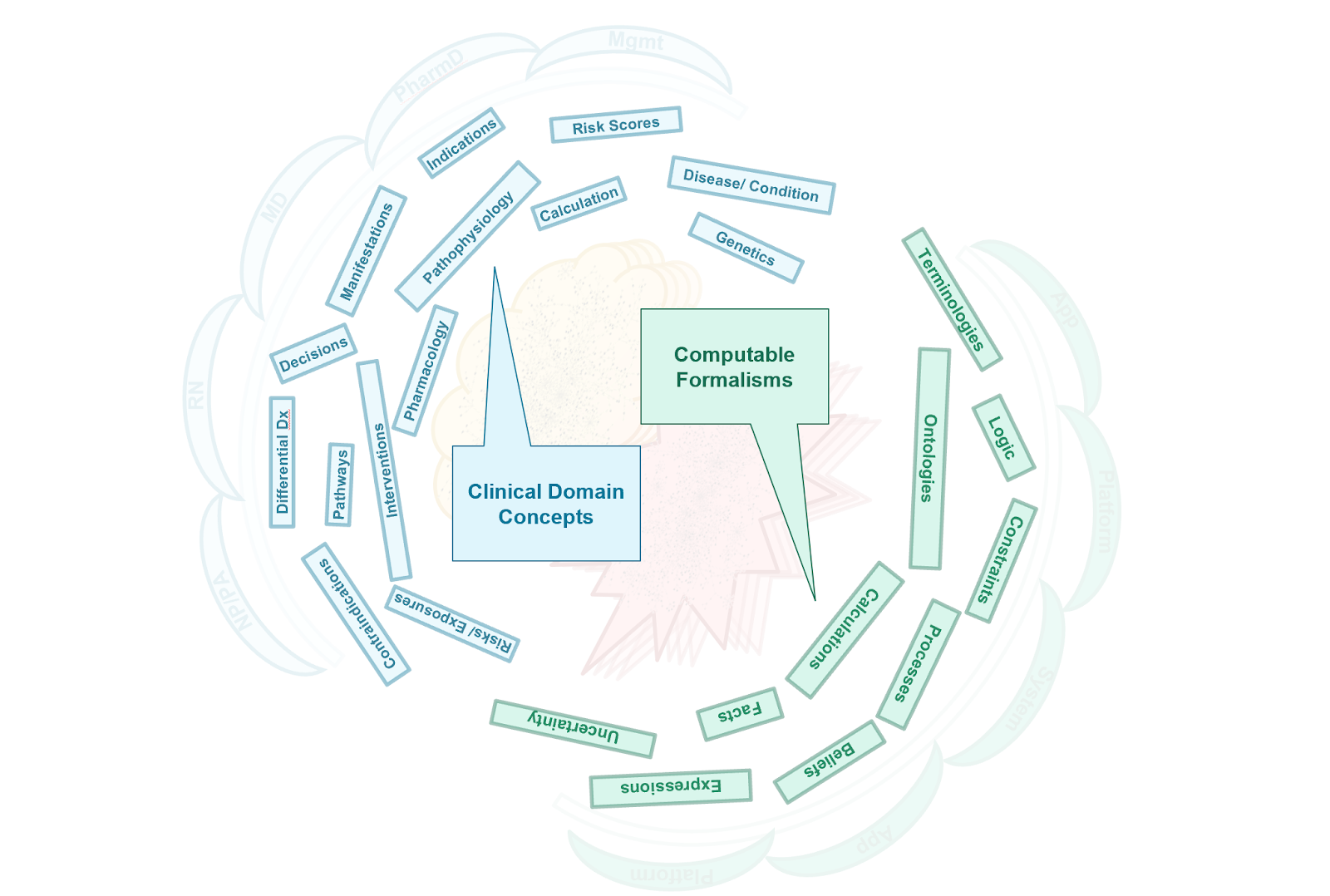

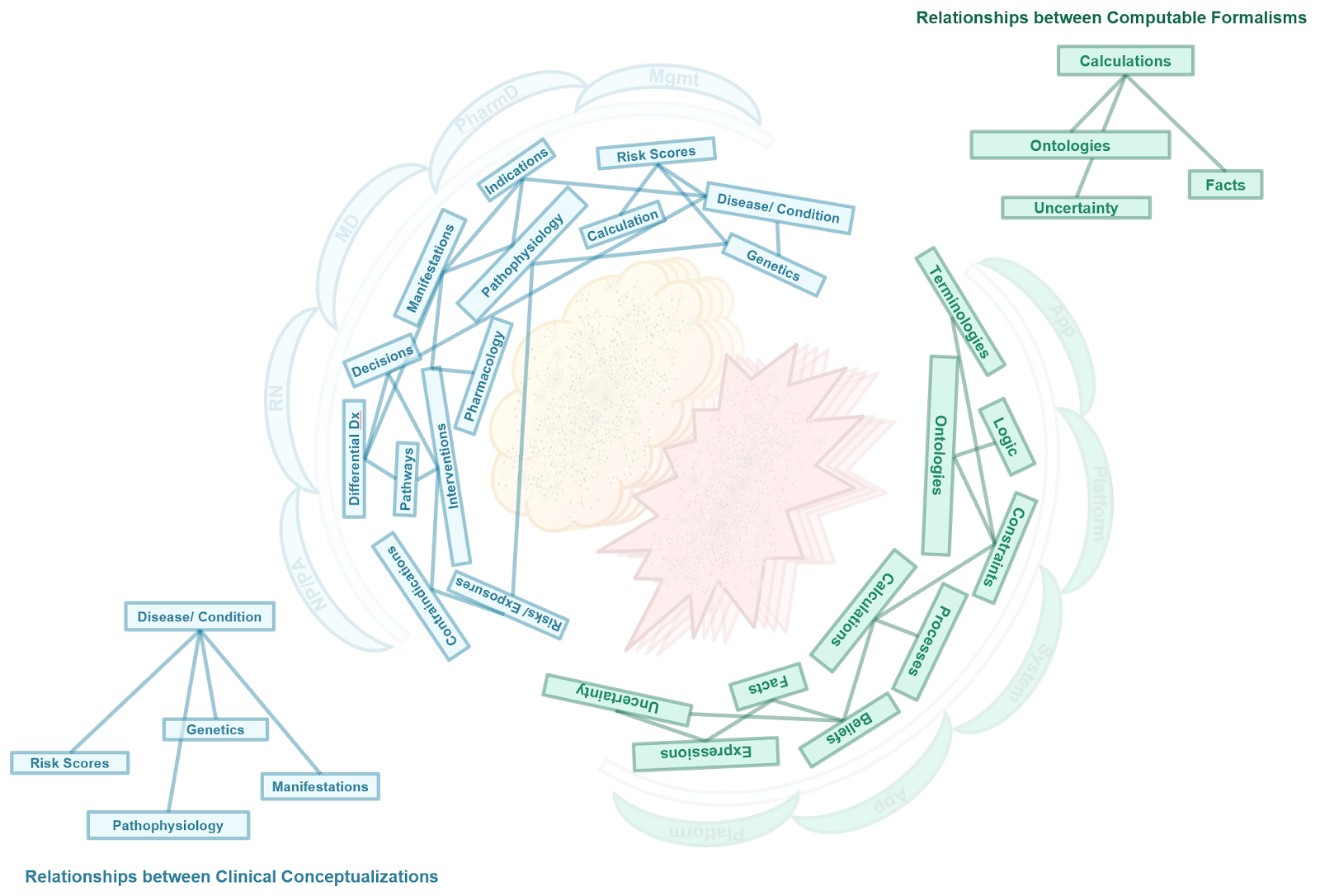

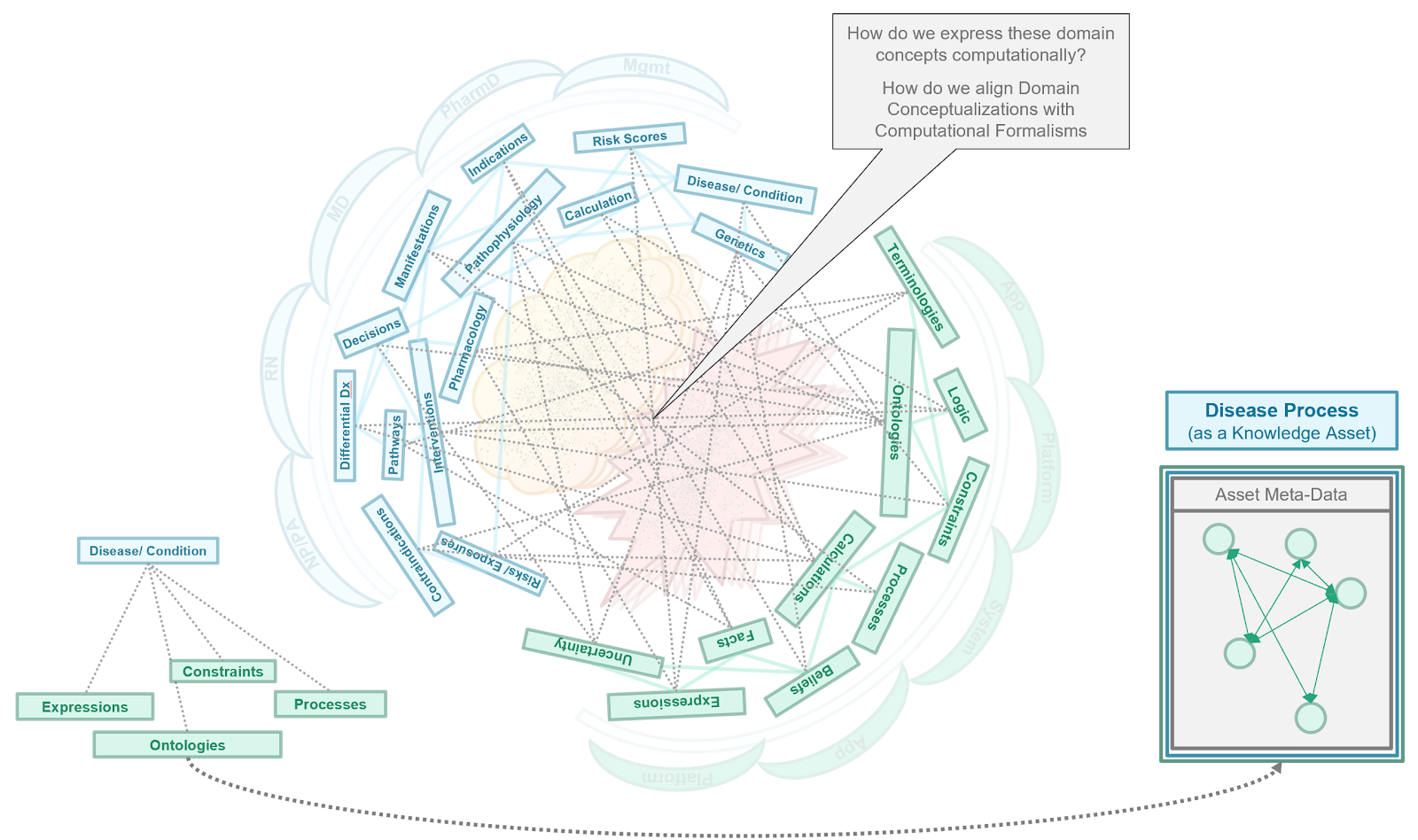

This brings us to the conceptual knowledge architecture for the CPG. It is the product of the concepts from a guideline and its recommendations described in the section on the Guideline Development Process together with the principles and best practices discussed previously in this section as well as the approach to developing the knowledge architecture described just above.

The conceptual perspective on the CPG knowledge architecture describes the domain- oriented descriptions of the knowledge assets or artifacts, together with their properties and relationships. In the Methodology Section, these knowledge assets are concretized and realized as explicit computable knowledge assets in CPG Profiles on FHIR Resources using an established approach from the HL-7 FHIR Clinical Reasoning Module.

Details of the CPG Knowledge Architecture (Conceptual Perspective) has an entire section dedicated to it with subsections dedicated to specific separations of concerns and CPG Concepts.

The CPG knowledge architecture provides the framework through which the knowledge engineering team realizes the guideline, its recommendations, and their various features through explicit formalisms and ultimately as information, which brings us to:

As discussed in the Knowledge Asset section previously, the asset metamodel (definition of structure including metadata, attributes, requirements and constraints) can be defined using an approach to Knowledge Artifact Representation in FHIR described in the Clinical Reasoning Module. In FHIR, the means of defining asset metamodels is the FHIR StructureDefinition Resource (though it is also used for definitions of resources other than knowledge assets including all request (e.g. orders) and event (e.g. clinical data element) resources). Furthermore, the PlanDefinition Resource (based on the HL-7 Knowledge Artifact Specification) is a base, or more generic, asset meta-model definition that may be profiled using StructureDefinition to further define additional asset meta-models through profiling.

Given the Conceptual Perspective on the CPG Knowledge Architecture, the principles, best practices, and development approaches described above together with the approach to Knowledge Artifact Representation in FHIR (described in part in the section in this implementation guide on Knowledge Assets), the CPG FHIR Profiles as described and defined in this guide, are the concentration of the CPG Knowledge Architecture- the formal representations of the metamodels used to express the CPG Concepts described in the conceptual knowledge architecture. The Methodology section of this guide describes how individual knowledge assets or artifacts are realized using these CPG Profiles.

As described above, it is critical in knowledge-driven approaches to identify accurate, representative, unambiguous, and useful domain knowledge abstractions and for these abstractions themselves to respect domain-oriented separations of concerns. These separations of concerns must be respected within and across the domain conceptualizations, as well as between knowledge formalizations and across the translations or transformations thereof. A related principle is fidelity to domain conceptualizations, where oversimplification leads to unwieldy and value-diminishing complexity to correct for gaps in fidelity, while appropriate complexity to align with the domain yields optimal formalizations.

However, healthcare by its nature seems to have significant ambiguity, particularly when a highly educated and trained healthcare professional is trying to describe how they think and work to a specially trained and educated information technology professional. In fact, this is why many knowledge engineers have dual training in both domains or the science that explicitly addresses the intersection (e.g., biomedical and clinical informaticians). Even for well-trained and experienced knowledge engineers and architects can have difficulty with boundary issues at the separation of domain concerns.

One of the most critical principles in dealing with these boundary issues is to identify them, recognize that they exist, and then formulate a plan to explicitly address them. To a large extent, this takes experience and faithfully adhering to knowledge architecture principles and best practices. While there are almost always trade-offs to be made as well as timelines to be met that must be further taken into consideration, the close, careful, and thoughtful attention to these boundary issues helps improve time and effort, value created, scalability, and adaptability. This is why architecting should happen before engineering and building.

There are several best practices for addressing these boundary issues once they have been identified. One such best practice is to use “Layers of Abstraction”. Creating abstraction layers is a means of hiding much of the working details of a component, allowing the separation of concerns to facilitate both interoperability within the knowledge architecture and across implementations thereof. In fact, the “concerns” themselves can be thought of as creating abstraction layers. Often when modeling or architecting a “concern”, one creates fit-for-purpose features for that concern that themselves may be abstracted, which specifically address boundary issues with ‘adjacent’ concerns with which it must interact.

In some cases, the boundary issue itself becomes fully abstracted as its own concern. Interfaces, or a means of interacting, between concerns may be thought of as one such way of abstracting the concern of the boundary issue itself. In other cases, shared concepts (e.g., as information objects) are a means of addressing the boundary. In other words, some lower-level domain concepts may be used by, used in, and/or belong to more than one concern but often playing somewhat different roles.

Boundary issues specific to the CPG Knowledge Architecture are discussed in the subsection on Separating and Defining Case, Plan, and Workflow.

The knowledge architecture is typically developed and manifested in a knowledge content management system since that is where all of the knowledge asset definitions (metamodels), knowledge asset metadata, knowledge asset content, the knowledge asset ontology, and the various features that leverage these capabilities reside. A knowledge content management system can further afford the ability to evolve and update the knowledge architecture and all its derivatives, while giving feedback to the knowledge architecture team on the impact of such changes. Likewise, additional knowledge asset definitions (metamodels including metadata model), can be developed in the knowledge content management system.

For more on the manifestation of the knowledge architecture in a content management system and means by which it might be informed and or evolved, see: