This page is part of the FHIR Specification (v0.4.0: DSTU 2 Draft). The current version which supercedes this version is 5.0.0. For a full list of available versions, see the Directory of published versions  . Page versions: R5 R4B R4 R3 R2

. Page versions: R5 R4B R4 R3 R2

The base FHIR specification (this specification) describes a set of base resources, frameworks and APIs that are used in many different contexts in healthcare. However there is wide between jurisdictions and across the healthcare eco-system around practices, requirements, regulations, education and what actions are feasible and/or beneficial.

For this reason, the FHIR specification is a "platform specification" - it creates a common platform or foundation on which a variety of different solutions are implemented. As a consequence, this specification requires further adaptation to particular contexts of use. Typically, these adaptations specify:

Note that because of the nature of the healthcare eco-system, there may be multiple overlapping set of adaptations - by healthcare domain, by country, by institution, and/or by vendor/implementation.

Typically, adaptations (either actual implementations or specifications - sometimes called "Implementation Guides") both restrict and extend APIs, resources and terminologies. FHIR provides a set of resources that represent the decisions that have been made, and allows implementers to build useful services from them. These resources are known as the conformance resources. These conformance resources allow implementers to:

These need to be used following the policies discussed below, and also following the basic concepts for extension that are described in "Extensibility". For implementer convenience, the specification itself publishes its base definitions using these same resources.

A conformance resource lists the REST interactions (read, update, search, etc) that a server provides or that a client uses, along with some supporting information for each. It can also be used to define a set of desired behavior (e.g. as part of a specification or a Request for Proposal). The only interaction that servers are required to support is the Conformance interaction itself - to retrieve the server's conformance statement. Beyond that, servers and clients support and use whichever API calls are relevant to their use case.

In addition to the operations that FHIR provides, servers may provide additional operations that are not part of the FHIR specification. Implementers can safely do this by appending a custom operation name prefixed with '$' to an existing FHIR URL, as the Operations framework does. The Conformance resource supports defining what OperationDefinitions make use of particular names on an end point. If services are defined that are not declared using OperationDefinition, it may be appropriate to use longer names, reducing the chance of collision (and confusion) with services declared by other interfaces. The base specification will never define operation names with a "." in them, so implementers are recommended to use some appropriate prefix for their names (such as "ihe.someService") to reduce the likelihood of name conflicts.

Implementations are encouraged, but not required, to define operations using the standard FHIR operations framework - that is, to declare the operations using the OperationDefinition resource, but some operations may involve formats that can't be described that way.

Implementations are also able to extend the FHIR API using additional content types. For instance, it might be useful to read or update the appointment resources using a vCard based format. vCard defines its own mime type, and these additional mime types can safely be used in addition to those defined in this specification.

Extending and restricted resources is done with a "Profile" resource, which is a statement of rules about how the elements in a resource are used, and where extensions are used in a resource.

What profiles can do is limited in some respects:

The consequence of this is that if a profile mandates extended behavior that cannot be ignored, it must also mandate the use of a modifier extension. Another way of saying this is that knowledge must be explicit in the instance, not implicit in the profile.

As an example, if a profile wished to describe that a Procedure resource was being negated (e.g. asserting that it never happened), it could not simply say in the profile itself that this is what the resource means; instead, the profile must say that the resource must have an extension that represents this knowledge.

There is the facility to mark resources that they can only be safely understood by a process that is aware of and understands a set of published rules. For more information, see Restricted Understanding of Resources.

A profile specifies a set of restrictions on the content of a FHIR resource or data type. Profiles are identified by their canonical URL, which should be the URL at which they are published. The following kinds of statements can be made about how an element is used:

All of these changed definitions SHALL be restrictions that are consistent with the rules defined in the base resource in the FHIR Specification. Note that some of these restrictions can be enforced by tooling (and are by the FHIR tooling), but others (e.g. alignment of changes to descriptive text) cannot be automatically enforced.

A profile contains a linear list of element declarations. The inherent nested structure of the elements is derived from the path value of each element. For instance, a sequence of the element paths like this:

defines the following structure:

<Root>

<childA>

<grandChild/>

</childA>

<childB/>

</Root>

or its JSON equivalent. The structure is coherent - children are never implied, and the path statements are always in order. The element list is a linear list rather than being explicitly nested because element definitions are frequently re-used in multiple places within a single profile, and this re-use is easier with a flat structure.

Profiles may contain either a differential statement, a snapshot statement or both.

Differential statements describe only the differences that they make relative to another profile (which is most often the base FHIR resource or data type). For example, a profile may make a single element mandatory (cardinality 1..1). In the case of a differential structure, it will contain a single element with the path of the element being made mandatory, and a cardinality statement. Nothing else is stated - all the rest of the structure is implied (note: this implies that a differential profile can be sparse, and only mention the elements that are changed, without having to list the full structure).

In order to properly understand a differential structure, it must be applied to the profile on which it is based. In order to save tools from needing to support this operation (which is computationally intensive - and impossible if the base structure is not available), a Profile can also carry a "snapshot" - a fully calculated form of the structure that is not dependent on any other structure. The FHIR project provides tools for the common platforms that can populate a snapshot from a differential.

Profiles can contain both a differential and a snapshot view. In fact, this is the most useful form - the differential form serves the authoring process, while the snapshot serves the implementation tooling. Profile resources used in operational systems should always have the snapshot view populated.

One common feature of profiles is to take an element that may occur more than once (e.g. in a list), and split the list into a series of sublists, each with different restrictions on the elements in the sublist with associated additional meaning. In FHIR, this operation is known as "Slicing" a list. It is common to “slice” a list into sub-lists containing just one element, effectively putting constraints on each element in the list.

Here is an example to illustrate the process:

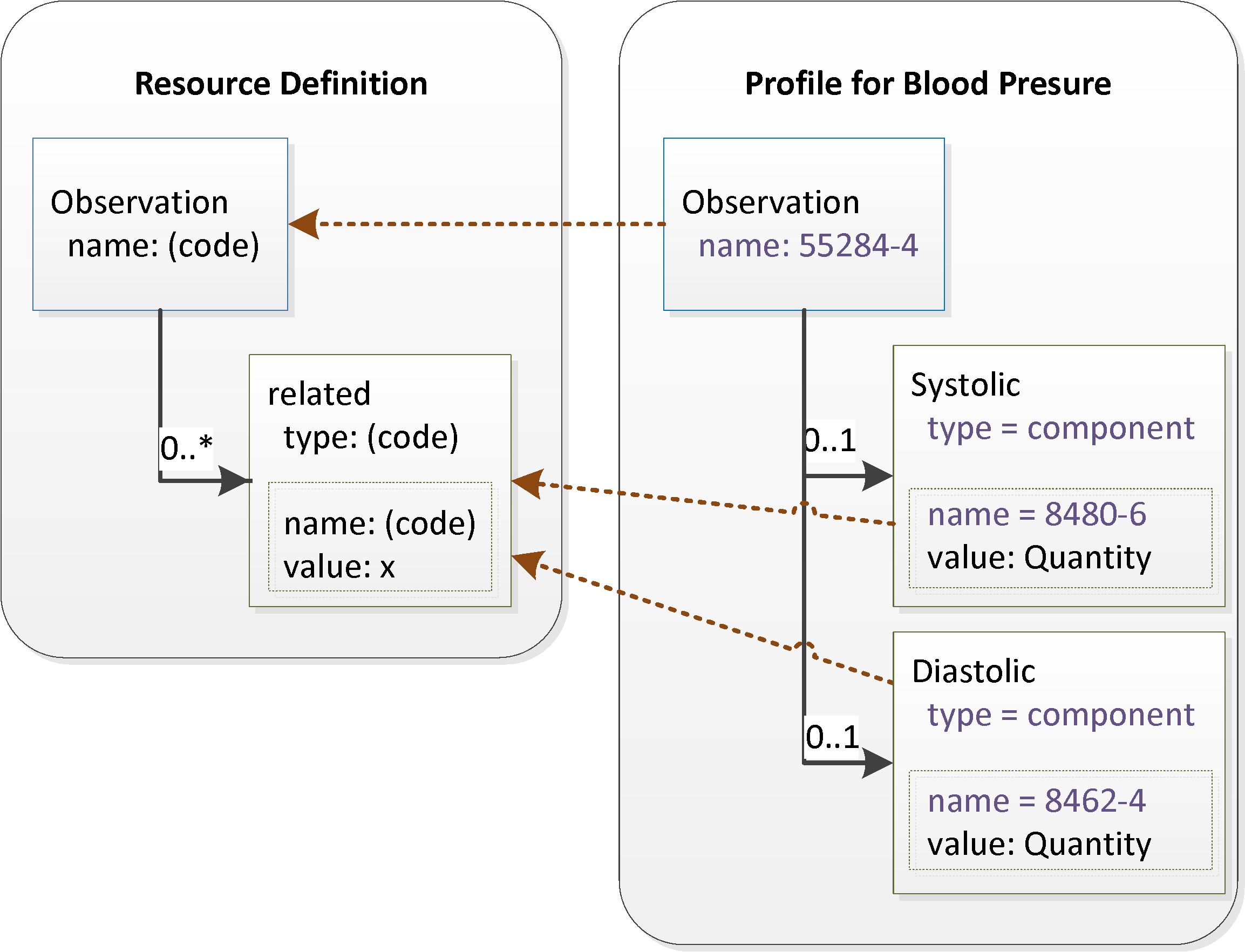

In this example, the base resource defines the "related" element which refers to another Observation which is related to the main Observation and which may occur multiple times. Each "related" element has a "type" element specifying the nature of the relationship (component, replacement, derivation etc.), and a "target" element which identifies the actual observation. In this diagram, for convenience, the contents of the target element are shown in the inner box instead of the showing the target reference explicitly. Also, to avoid adding clutter to this simplified example, the "name" attribute of Observation is shown as just a code not a full CodeableConcept.

The profile for Blood Pressure constrains the related element list into 2 sublists of one element: a systolic element, and a diastolic element. Each of these elements has a fixed value for the type element, and the profile also fixes the contents of the target observation as well, specifying a fixed LOINC code for the name and specifying that both have a value of type Quantity. This process is known as "slicing" and the Systolic and Diastolic elements are called "slices".

Note that when the resource is exchanged, the wire format that is exchanged is not altered by the profile. This means that the item profile names defined in the profile ("systolic", etc. in this example) are never exchanged. A resource instance looks like this:

<Observation>

...

<related>

<type value="component"/>

<target ...> <!-- has the name "8480-6" -->

</related>

<related>

<type value="component"/>

<target ...> <!-- has the name "8462-4" -->

</related>

</Observation>

In order to determine that the first related item corresponds to "Systolic" in the profile to determine to which additional constraints for a sub-list the item conforms, the system checks the values of the elements - in this case, the name element in the resource that target refers to. This element is called the “discriminator”.

In the general case, systems processing resources using a profile that slices a list can determine which profile slice an item in the list by checking whether its content meets the rules specified for the slice.

This requires for a processor to be able to check all the rules applied in the slice and to do so speculatively in a depth-first fashion. Neither of these is appropriate for an operational system, and particularly not for generated code. For this reason, a slice can nominate a set of fields that act as a "discriminator" - they are used to tell the slices apart.

When a discriminator is provided, the composite of the values of the elements nominated in the discriminator is unique and distinct for each possible slice and applications can easily determine which slice an item in a list corresponds to. The intention is that this can be done in generated code.

When a profile nominates one or more discriminators, it SHALL fix the value of the element for each discriminator for each slice, or if the element has a terminology binding, it SHALL be associated with a complete binding with a version specific Value Set reference that enumerates the possible codes in the value set. The profile SHALL ensure that there is no overlap between the set of values and/or codes in the value sets between slices.

It is the composite (combined) values of the discriminators that are unique, not each discriminator alone. For example, a slice on a list of items that are references to other resources could nominate fields from different resources, where each resource only has one of the nominated elements, as long as they are distinct across slices.

A profile is not required to nominate any discriminator at all for a slice, but profiles that don't identify discriminators are describing content that is very difficult to process, and so this is discouraged.

Within a profile, a slice is defined using multiple element entries that share a path but have distinct names. These entries together form a "slice group" that is:

The value of the discriminator element is a path name that identifies the descendant element using a dotted notation. For references, the path transitions smoothly across the reference and into the children of the root element/object of the resource. For extensions, an extension can be qualified with the URL of the extensions being referred to. There are two special names: @type, and @profile. Here are some example discriminators:

| Context | Discriminator | Interpretation |

| List.entry | item.reference.name | Entries are differentiated by the name element on the target resource - probably an observation, which could be determined by other information in the profile |

| List.entry | item.reference.@type | Entries are differentiated by the type of the target element that the reference points to |

| List.entry | item.reference.@profile | Entries are differentiated by a profile tag on the target of the reference, as specified by a profile (todo: how to do that?) |

| List.entry | item.extension["http://acme.org/extensions/test"].code | Entries are differentiated by the value of the code element in the extension with the nominated URL |

| List.entry.extension | url | Extensions are differentiated by the value of their url property (usually how extensions are sliced) |

| List.entry | item.reference.@type, item.reference.name | Extensions are differentiated by the combination of item.reference.name, and, if it has one, the name element. This would be appropriate for where a List might be comprised of a Condition, and set of observations, each differentiated by it's name - the condition has no name, so that is evaluated as a null in the discriminator set |

See also examples of slicing and discriminators.

An extension definition defines the url that identifies the extension and which is used to refers to the extension definition when it is used in a resource.

The extension definition also defines the context where the extension can be used (usually a particular path or a data type) and then defines the extension element using the same details used to profile the structural elements that are part of resources. This means that a single extension can be defined once and used on different Resource and/or datatypes, e.g. one would only have to define an extension for “hair color” once, and then specify it can be used on both Patient and Practitioner.

For further discussion of defining and using extensions, along with some examples, see Extensibility.

Once defined, an extension can be used in an instance of a resource without any Profile declaring that it can, should or must be, but Profiles can be used to describe how an extension is used.

To actually prescribe the use of an extension in an instance, the extension list on the resource needs to be sliced. This is shown in the extensibility examples

Note that the minimum cardinality of an extension SHALL be a valid restriction on the minimum cardinality in the definition of the extension. if the minimum cardinality of the extension is 1 when it is defined, it can only be mandatory when it is added to a profile. This is not recommended - the minimum cardinality of an extension should usually be 0.

Coded elements have bindings that link from the element to a definition of the set of possible codes the element may contain. The binding identifies the definition of the set of possible codes and controls how tightly the set of the possible codes is interpreted.

The set of possible codes is either a formal reference to a ValueSet resource, which may be version specific, or a general reference to some web content that defines a set of codes. The second is most appropriate where set of values is defined by some external standard (such as mime types). Alternatively, where the binding is incomplete (e.g. under development) just a text description of the possible codes can be provided.

Bindings have two properties that define how the set of codes is used: isExtensible and conformance.

isExtensible indicates whether additional codes and/or plain text are allowed beyond those in the defined set of codes.

| false | No additional codes are to be used beyond the list provided |

| true | Supplemental codes or plain text may be needed (this is common because it is frequently the case that concepts will need to be used which won't be in the defined set of codes) |

Conformance indicates the expectations for implementers of the specification. There are three possible values:

| required |

Only codes in the specified set are allowed. If the strength is 'extensible', other codes may be used for concepts not covered by the value set but cannot be used for concepts covered by the bound code list, even if a profile constrains out some of those codes). |

| preferred | For greater interoperability, implementers are strongly encouraged to use the bound set of codes, however alternate codes may be used in profiles if necessary without being considered non-conformant. |

| example | The codes in the set are an example to illustrate the meaning of the field. There is no particular preference for the set's use. |

The interplay between the meaning of these is subtle but sometimes important. The following table helps define the meanings:

| Conformance | isExtensible=false | isExtensible=true |

| Required | Implementers SHALL use a code from the defined set | Implementers SHALL use a code from the defined set if one is applicable, but otherwise may provide their own code or use text |

| Preferred | Implementers SHOULD use a code from the defined set Using a different code will generate a warning from a validator | Implementers SHOULD use a code from the defined set if one is applicable, but MAY provide their own code or use text |

| Example | Implementers MAY use a code from the defined set, or provide their own code, or use text |

Note: Example binding isExtensible = false is not generally a useful statement.

Value Set resources can be used to define local codes (Example) and to mix a combination of local codes and standard codes (examples: LOINC, SNOMED), or just to choose a particular set of standard codes (examples: LOINC, SNOMED, RxNorm). Profiles can bind to these value sets instead of the ones defined in the base specification, following these rules:

| Binding Type in base specification | Matching Profile Properties | Customization Rules in Profiles |

| Complete | conformance = required, extensible = false | The value set can only contain codes contained in the value set specified by the FHIR specification |

| Incomplete | conformance = preferred and extensible = true | The value set can contain codes not found in the base value set. These additional codes SHOULD not have the same meaning as existing codes in the base value set |

| Example | conformance = example | The value set can contain whatever is appropriate for local use |

One property that can be declared on profiles that is not declared on the resource or data type definitions is "Must Support". This is a boolean property. If true, it means that systems claiming to conform to a given profile must "support" the element. This is distinct from cardinality. It is possible to have an element with a minimum cardinality of "0", but still expect systems to support the element.

The meaning of "support" is left deliberately ambiguous. Examples might include:

The specific meaning of "Must Support" for the purposes of a particular profile SHALL be described in the Profile.description or in other documentation for the implementation guide the profile is part of.

If creating a profile based on another profile, Must Support can be changed from false to true, but cannot be changed from true to false.

The final thing implementations can do is to define search criteria in addition to those defined in the specification itself. Search criteria fall into one of four categories:

Additional Search Parameters can be defined using the SearchParameter resource.